Nikola Tesla was an amazing human being - he helped forge the modern world, and David Bowie played him badly in a movie - but to like him, you kind of have to accept the fact that he believed in eugenics. His idea that humanity should be selectively bred based on perceived strong traits, forcibly sterilizing those deemed unfit to procreate is… unfashionable. This isn’t going to be the paper-thin intro metaphor it seems - Massive Chalice relies on eugenics, builds itself around them. The game’s make-up forces you to become, at a base level, the individual writing the design document for humanity. But here we find a reverse-Tesla - the eugenics are the bit you’ll enjoy most.

The set-up is a mixture of the familiar and the charmingly absurd. Your kingdom is under attack, you are an immortal being with some kind of connection to the titular Chalice (which for no reason narrates the game in two different voices), and you have to survive for 300 years until said vessel can charge up enough to blow up all evil with magic. To do this, you play a combination management-strategy game that could be called a blood relative of XCOM - if that term meant someone who had pushed someone else into a corner, stuck a needle in their arm and stolen all their blood.

Your base is a multi-region kingdom - you can build Keeps that spawn warriors, Crucibles that offer them more experience, or Guilds that speed up research. Research, among other things, offers improvements for each of the game’s three intriguing classes - Hunters with shoulder-mounted bows, lightly-armoured, bomb-toting Alchemists, and Caberjacks, battering ram-wielding melee tanks.

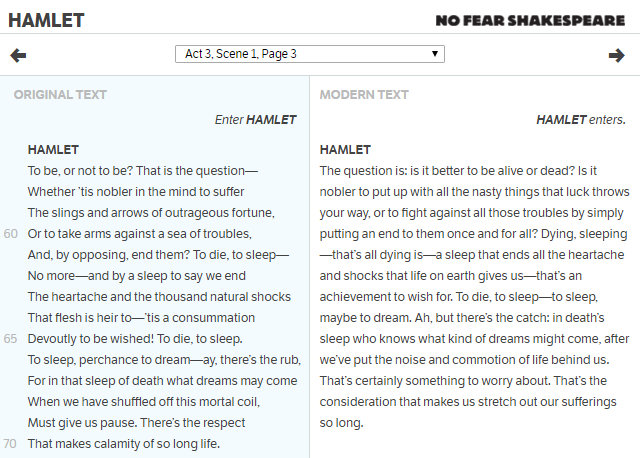

When the kingdom’s attacked, it becomes a turn-based squad-tactics game, spiced up by the increasingly overworked spectre of permadeath. Every hero on the field has two action points per turn, used for movement, basic attacks and special skills (and yes, accuracy ratings still reduce attacks to occasionally hugely frustrating dice rolls). They can level up as you play, allowing you to specialise their skills, even earning them cute little nicknames in the process. There’s a terrifyingly opaque fog of war. Enemies will pounce and punish you for the slightest mistake. It’s XCOM, basically.

The game offers one break from the manage-battle-manage XCOM rhythm, in the form of mini-text adventure moments. You'll be presented with many (usually weird) decisions to make, from national politics to what to do when a school trip comes to your Citadel. The results are usually more catastrophic than you'd expect - I sent a man through a portal and he lost his genitals.

The difference, then, isn’t one of mechanics, but scale. With 300 years to wait, and immortality at a premium, permadeath extends to more than getting some eldritch beast’s talon stuck through your temple - old age is the biggest killer of all. You fight this by setting up Bloodlines - every time you build a Keep, you install a Regent, who lends their surname and their reproductive organs to the cause. You then choose them a partner, and sit back to wait for the not-onscreen magic to happen. When they die, you choose one of their children to be a successor, and the line continues.

Here’s where eugenics comes in. Every character has Traits and Personality modifiers. While personalities are mutable - they can be learned from parents, Citadel teachers, even squadmates - traits are directly passed down, meaning you want a Regent and Partner pairing to be strong as bears and free of, say, heart disease. Their classes are important, too - cross-breeding two classes leads to hybrid styles. Hunters can suddenly strap Alchemists’ bombs to their arrows, melee types can use stealth to their advantage.

The vaguely chilling effect is that you can be quite glad your 70 year-old Regent’s Partner has just died, because you’ve just spotted a fertile teenage Caberjack who’ll spawn some powerful new type of war-baby. That said, you don’t want either of the pairing to be too excellent, because assigning them these positions means they can never be used in battle. In Massive Chalice, sex is a full-time job.

This system cuts both ways. The length of time between battles means, unlike XCOM, you get relatively little time to get attached to soldiers - they’ve generally got six battles in them before they cork it. That said, you will get attached to lines as a whole. The Gritfish family, a proud lineage of melee warriors, spoiled only slightly by one poorly-chosen husband who’s made the entire line slightly too stupid to help out with research. Or the doomed Baltocles clan, whose best ever warrior created a Relic Weapon, only for the effects of inbreeding to have it passed down to a nervous, nearsighted old man who promptly blew himself up, killing the family name in the process.

It’s intriguing, for sure, but on a design level it can lead to a dead end you could never foresee - a bad bloodline can doom you a century (or, in real-life terms, several hours) before you realise. Even then, you could become a little bored of proceedings. The six enemy types - weird as they are, able to steal your XP, or even age your warriors to death - become predictable very quickly. Research is limited enough that you have barely any room to experiment - replay value comes only if you’re interested in being increasingly efficient, rather than creative.

Eugenics is, perhaps fittingly, the game’s strongest trait. It offers you a measure of control over your heroes, a sense of micro-management mastery over the world. But the game’s other characteristics are weaker, an impression of XCOM, rather than a successor to it. It seems I can’t resist the metaphor after all: like Tesla, there’s brilliance here, but the flaws are hard to ignore.

Mortal Kombat X Guide: How to Play Quan Chi

Mortal Kombat X Guide: How to Play Quan Chi The Year Of Luigi Comes to an End

The Year Of Luigi Comes to an End Dark Souls 2 - The Lost Sinner Boss Fight Walkthrough

Dark Souls 2 - The Lost Sinner Boss Fight Walkthrough Mind Blown: 40 Final Fantasy Secrets & Facts

Mind Blown: 40 Final Fantasy Secrets & Facts Fallout 4: All Side Quests Walkthrough

Fallout 4: All Side Quests Walkthrough