The beauty of video games is that they’re interactive, meaning you can play them however you wish. This may not be as true in an online multiplayer setting, but is certainly true for single player games. The culture of speedrunning is a perfect example.

Some people play games for the story and characters. Others play to relax, to take it slow, or to kill time when they’re bored. And then there are those who want to challenge themselves to the extreme. In a lot of ways, the challenge is the heart of gaming.

This can manifest in a few ways. Of these challenge-seekers, many prefer to test their mettle against other players — either in a heads-up or a team-vs-team environment. The rest prefer to compete against themselves. That latter group is where speedrunning truly shines.

In simplest of terms, speedrunning is the completion of a certain level or stage in a game, or the entire game itself, as quickly as possible. If the game has a built-in completion timer, then that’s often used to determine official times. If not, third-party helper tools exist as well.

As a concept, “racing against oneself” is as old as humanity itself, so in that sense speedrunning doesn’t really have a beginning. Even in the context of video games, players have undoubtedly been “self-racing” for as long as games have been around.

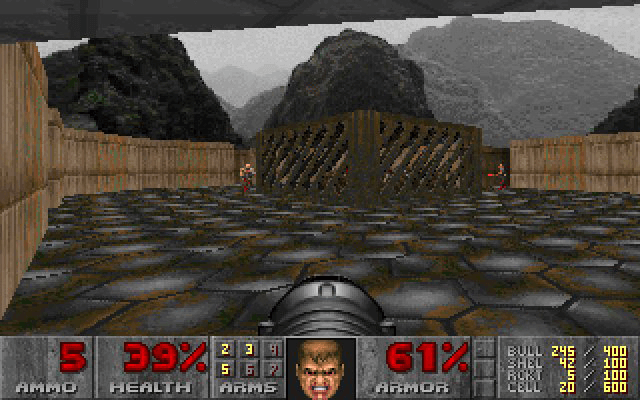

But as a social activity? The overall consensus is that the true spirit of speedrunning officially began with Doom.

Why Doom? Because it launched with two very important built-in features that made it possible to record one’s time and prove that it was legitimate. The first feature was an end-of-level clock that displayed the exact completion time. The second feature was the ability to record demos.

A demo, or demonstration, was a recording of the player’s exact playthrough of a particular level. This demo file could be distributed to others, loaded into their copy of Doom, then viewed from start to finish. The ability to share speedruns made it possible for players to compete through a single player game in an age where online multiplayer was rare.

About a year after Doom launched, Simon Widlake opened a website called COMPET-N which was to be an online ranking of the fastest Doom playthroughs. Though the “speedrun” term wouldn’t be popularized until later, COMPET-N is widely recognized as the first speedrunning website.

Thus, speedrunning was born.

Over the years, the activity evolved and developed several nuances. One such nuance can be posed as a question: “Does it count if glitches are involved?” Another nuance: “How much of the game needs to be completed?” These questions, and others like them, caused schisms within the community.

As a result, there are now several types of speedruns:

As far as glitches are concerned, there are purists in the community who believe that they invalidate a speedrun. For the most part, however, glitch exploitation has come to be a normal — even expected — aspect of speedrunning. In most games, nearly all but the most game-breaking glitches are allowed.

This argument about glitches is one that speed runners like myself have had to have countless times over the years. It really comes down to a few simple things that easily explain why glitches are perfectly acceptable in almost every case.

The fact of the matter is that anything that’s doable within the game without external interference is fair play, because even if it wasn’t intended by the developers, it’s still part of that package. Your goal is to reach the end of that self-contained game as quickly as possible by any means necessary. If using glitches yields the fastest time, then so be it.

That being said, there are of course exceptions to every rule. It’s rare, but if a particular glitch is so completely game-breaking that it makes the speed run more-or-less pointless, that game’s speed running community might largely choose to ignore runs using that glitch, or at least focus on separating runs using it and not using it into separately considered categories.

HT: What’s Your Tag?

Which brings us to our final nuance: the tool-assisted speedrun (TAS). This kind of speedrun uses a third-party tool to alter certain aspects of gameplay in order to compensate for limitations in player ability. For example, one tool might reduce the game to slow motion, allowing the player to exploit glitches that might otherwise be extremely difficult to pull off.

But why?

Many non-speedrunners look at the prevalence of glitch abuse and tool assistance and wonder, “What’s the point of playing the game if you aren’t going to play it properly?” While that kind of thinking holds a lot of weight in a non-speedrun context, it turns out that speedrunners think about games in a completely different way than most people.

To the speedrunner, games cease being seen as games; instead, they become puzzles. With a self-imposed goal (some % completion) and a set of constraints (e.g. no upgrades and no warps), the speedrunner must figure out the path of least resistance using whatever methods are valid within those constraints.

Let’s peel back what it means to play a game for a bit.

Video games, at their core, are just computer programs. When a human plays a game, they are feeding instructions to the program to act on. We perceive this as a continuous interaction where our inputs from a controller instantly affect game operation.

In reality, however, the program works in stepped increments and only checks whether you are providing inputs at the beginning of each step. A single step is referred to as a “frame” in both the technical and speedrunning sense.

At the core, this is what a speedrun is: an attempt to optimize the path through a game by completing it in the fewest frames possible.

HT: Speed Demos Archive

The mindset of the speedrunner is one of optimization. It’s all about shaving precious seconds here and there in the hopes that they’ll add up to a new record. The game no longer exists. It’s simply there to provide the speedrunner with a problem to optimize.

Needless to say, not everyone is fit to be a speedrunner.

First, the speedrunner must be familiar with the game they’re about to solve. While it’s not necessary to know everything , it’s true that the more he knows, the better equipped he’ll be for success. At the extreme, this means studying the gameplay mechanics, understanding in-game physics, memorizing tricks and glitches, etc.

In a game like Super Meat Boy, timing is crucial. It’s one thing to know the movement patterns of various hazards, but the best minds will know the exact position of a given hazard at any given time. This attention to detail is what allows a skilled speedrunner to perform using nothing but muscle memory.

In a game that isn’t so reliant on dexterity and execution, the key to a fast time is exploiting as many shortcuts as possible, whether that means bypassing bosses, abusing certain mechanics, etc. For example, well-known Secret of Mana speedrunner StingerPA uses a trick that allows him to deal 999 damage per hit as a way to defeat bosses without having to grind and level up.

Another key component is perseverance and endurance. While certain games can be beat within a matter of minutes, many games have world record times that span several hours. The ability to maintain mental clarity for such long periods of time is a highly underestimated skill.

More often than not, a speedrunner will get to the end of his five-hour speedrun and realize that he was three seconds short of beating his record. That can be a maddening experience and only the most steel-minded players can muster up the strength to keep trying.

Speedrunners, like any other kind of competitor, also need dedication and diligence. It sounds weird to “practice” a speedrun, but that kind of tenacity is necessary to break records. Practicing is essential no matter how trivial it seems, or how painful it is to play the same game on repeat.

Heartbreak about sums it up. For as fast as these players are whipping through the games they have set out to master, speedruns can actually take many hours for each attempt.

Wright’s Wind Waker record is 4:27:53. That means speedrunners can play, and the audience can watch, for the better part of an evening only to make one tiny mistake and have to junk the whole thing.

The agony of defeat comes much more often than the thrill of victory.

HT: Wired

And practicing doesn’t just mean “playing the game on repeat”. There’s a lot of research that must be done, especially if players have been speedrunning a particular game for a long time. Certain routes will be deemed optimal and it’s the speedrunner’s job to optimize those routes even further.

How are routes optimized? Well, going back to the Super Meat Boy example, optimization is solely about speed of execution. For Secret of Mana, however, massive chunks of the game can be skipped based on storyline decisions and glitches. This is called “sequence breaking”.

How are glitches found? Usually by accident or luck. However, there are a few speedrunners who have so much technological knowledge that they can manipulate the actual memory of the game to surprising success. Rather than me explaining how this works, see for yourself:

All that being said, when we consider the speedrunning demographic, most participants fall into one of two categories:

The first kind of speedrunner is one who enjoys the thrill of improvement. They pick a game, speed through it as fast as they can, then repeat a few more times, beating their record with each subsequent playthrough. Their sole reason for speedrunning is to see that broken record at the end.

But speedrunning as an activity has diminishing returns. It’s much easier for him to beat his first record than it is to beat his tenth record. As he keeps playing, he approaches a limit — and eventually stops improving. Frustrated with this obstacle, he moves onto another game.

Let me be clear: I believe this is definitely a valid form of speedrunning. Just because you can’t match a world record doesn’t mean you shouldn’t race. I’m merely describing one kind of speedrunner, and these happen to be the majority.

The second kind of speedrunner is one who enjoys the process of discovery. They obviously enjoy the thrill of improvement as well, but it isn’t their primary motivation. Rather, they take pleasure in the entire journey: learning every nuance, finding new glitches, looking for areas where they can shave another two seconds off their time, etc.

When you watch this kind of speedrunner, you can feel the passion simply in the way they play the game. They’ll play the same damn game a million times and love it more with every Game Over. These are the ones who set world records. It’s unbelievable — and in some ways, even inspiring.

All this talk of speedrunning and we’ve only mentioned a handful of games. It might sound like a niche hobby — and in many ways, it is — but there are dozens, maybe even hundreds, of games that are actively being speedrun.

Think I’m kidding? The community for the very first Doom is still alive and well. It may not be as thriving as it once was, but rest assured that people are still breaking records even after all of these decades.

Other fan-favorite first-person shooters include Quake and Mirror’s Edge.

Platformer games, both 2D and 3D, make up a separate but huge chunk of the speedrunning arsenal. Several of the titles in the Super Mario franchise are good for beginners because most people are familiar with the series. Indeed, Super Mario World and Super Mario 64 are two of the most popular speedrunning games today.

Indie platformers are also quite popular. The roguelite adventure Spelunky, which rose to fame for its procedurally-generated levels, feels tailor-made for all kinds of speedrunning antics. And what about VVVVVV and Super Meat Boy, both of which can feel impossible to beat at times?

One title in particular was actually built with the speedrunning community as its target audience: Dustforce. This game is hard and anyone who breaks a record in it is worthy of much praise.

On the other side of the spectrum we have Minecraft, a game that’s known for being open-ended, creative, and pioneering the trend of procedural generation in modern gaming. There’s no way to win in Minecraft; you just keep playing until you die (in Hardcore mode) or get bored. So, how can anyone speedrun it?

Well, one day, somebody decided to start a new world and see how quickly they could reach and kill the Ender Dragon. Despite being the big boss of Minecraft, killing it doesn’t end the game. Still, putting a timer on it definitely makes it more interesting.

Regarding Minecraft speedruns, there’s another nuance to consider: random seed or set seed? Minecraft procedurally generates its terrain and entities using a seed value. By using a set seed, the world is always the same, thus allowing players to compete under the same parameters:

I could go on and on with speedrunning examples, but I’ll stop here because we still need to answer an important question. What makes a good speedrunning game?

For starters, there should be an active skill component. In other words, there must be some level of execution difficulty that allows a skillful player to differentiate themselves from a lesser-skilled player. For the most part, this means excluding story-driven games like The Walking Dead and artsy exploration games like Dear Esther.

You must have influence over the timing. That immediately rules out any on-rails shooters like Time Crisis and predictable shoot-em-ups like Ikaruga. One workaround, however, is to see how fast you can reach a certain point score, but some don’t consider that to be in the spirit of speedrunning.

Along those lines, there must be a clear end goal. Usually this end goal is determined by the game itself, such as defeating a final boss or clearing the last stage. If the game doesn’t offer a goal, the community can come together and decide on an arbitrary one (such as the Minecraft example above).

Luck should be a minimal factor. It’s immensely frustrating when luck ends up being the deciding factor between winning or losing a run. Some speedrunning communities try to mitigate luck’s impact by putting the target behind hours of gameplay (e.g. Spelunky) or by focusing on short, highly repeatable goals (e.g. The Binding of Isaac).

Lastly, it shouldn’t take too long to complete. I’ve seen people do speedrunning marathons before (e.g. beating every single Final Fantasy game in consecutive order) but that doesn’t mean those games are good for speedrunning. This rule is obviously subjective. I personally think that if it takes more than a few hours, it’s too long.

As it turns out, many games satisfy the above criteria, and even the ones that don’t can still be speedrun. That’s why when people ask, “Which game should I speedrun?”, the most common response is, “Pick a game that you enjoy playing over and over.”

Because, ultimately, that repetition is the heart of speedrunning.

Take a look at the gaming community as a whole and you’ll notice that there’s been a massive shift in the way we experience games. While the primary function of a game is to play it, we’re starting to see a new movement where enjoyment comes from the fact that we get to watch it.

I am, of course, talking about the advent of Twitch live streaming. While Twitch has always had close ties with the competitive gaming community, it’s not just about esports anymore. Millions from around the world tune into Twitch every day just to watch people play whatever they’re playing.

(Some may find this to be an incredibly nerdy activity, but in a lot of ways it’s no different than watching live television. Twitch has talk shows, competitions, and celebrity personalities — they just happen to be gaming-related.)

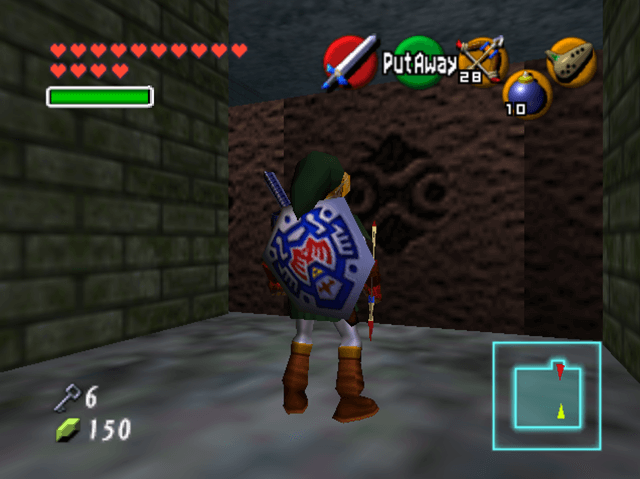

What does this have to do with speedrunning? Well, Twitch’s boom in popularity over the years has indirectly brought some much needed attention to the speedrunning community. Every day, thousands of viewers tune into live speedruns of The Binding of Isaac, Spelunky, Portal, The Legend of Zelda, and more.

Prior to Twitch, all we had was demo files and YouTube recordings. For the first time in history, people from across the world can watch someone break a world speedrun record as it happens.

Not only that, we now have full-blown events dedicated to speedrunning. For instance, just a few months ago there was Awesome Games Done Quick, which is a video game marathon event that raises money for various charities including Doctors Without Borders and Prevent Cancer Foundation.

In 2015, Awesome Games Done Quick managed to raise $1,575,000 for Prevent Cancer Foundation. How did they raise this much money? Through PayPal donations, basically. The speedrunning marathon is just a means of raising awareness and encouraging viewers to make a donation if they so desire.

You can watch all of the speedruns from both Awesome Games Done Quick 2015 and Summer Games Done Quick 2014 on the Games Done Quick YouTube channel. Between the two events, you’ll find over 300 videos.

And speaking of Summer Games Done Quick, you should know that the 2015 event will be taking place between July 26th and August 1st in St. Paul, Minneapolis, which makes this the perfect time to get into speedrunning. Registration details and pricing information is available on their website.

Want to learn more? Check out what we considered to be the highlights of Summer Games Done Quick 2014.

Yet as great as the Games Done Quick series have been for speedrunning awareness, most of the credit belongs to the long-standing communities that existed long before the arrival of Twitch, streaming, and live spectatorship.

In fact, it’s almost legendary how long these communities have survived considering how niche the activity used to be. Let’s take a look at some of the more influential names of the past couple decades:

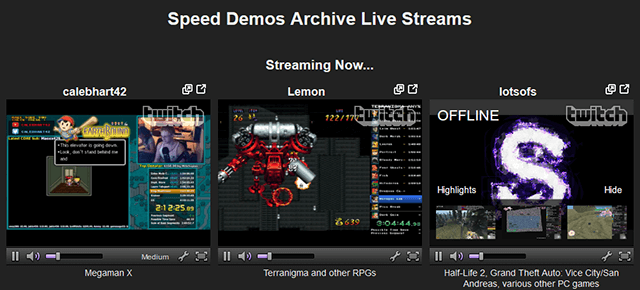

Speed Demos Archive is the throne room of speedrunners. It launched in 1997, back when it was called Nightmare Speed Demos and only acted as a repository for Quake speedruns on the Nightmare difficulty, but has since morphed into something greater despite the archaic web design.

The site is now an archive of the best user-submitted speedruns for over a thousand different games. Only the best runs for each game are kept and site visitors can watch full runs through embedded videos. Each submission is accompanied by the runner’s thoughts and commentary, which adds a nice human touch.

Submissions fall into three categories:

Each submitted run is verified by trusted community members, so you can rest assured that these are legit. Oh, and Speed Demos Archive is the group that hosts the aforementioned Games Done Quick series. How cool is that? These guys deserve much praise for their energy and dedication.

Speedruns Live is another big speedrunning website that isn’t dedicated to any particular game. What makes this one different, then? Their name is a dead giveaway: Speedruns Live revolves around the concept of racing, where two or more players race in real time.

As simple as the concept is, it’s actually quite fun to participate — even as nothing more than a viewer. Why? Because most of them are required to be streamed live, especially if the game is a PC title or played by means of an emulator on PC.

The website is just an anchor. The actual community congregates on Internet Relay Chat (IRC), which is a glorified chatroom for those who aren’t familiar with it.

Everyone obeys a set of rules and they tend to take it pretty seriously despite the fact that everything is for fun here. The channel also has a dedicated bot that automates the process, making it easier for everyone to start races and track winners and what not.

Want to check it out? Visit the Speedruns Live channel with their web client right now.

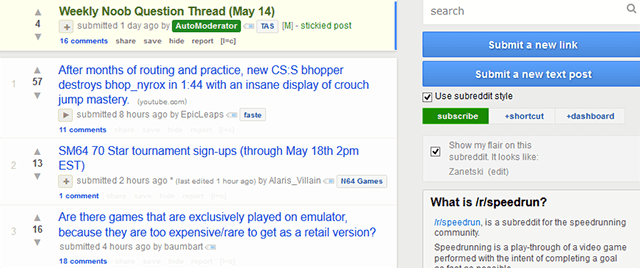

What if you’re an avid user of Reddit? Is there a subreddit community out there for you? There sure is. Hop on over to /r/speedrun for your daily dose of speedrunning goodness, and they’re welcoming whether or not you’re a brand new runner or a veteran with world records.

On your first visit to the subreddit, you’ll see a lot of threads prefixed by [PB] and [WR], which stand for Personal Best and World Record, respectively. News announcements are another common thread type (such as for upcoming events).

Speaking of events, you’ll also notice that there’s a section on the sidebar for Upcoming Marathons. Marathons are common in the speedrunning community and this subreddit provides a central location where you can stay on top of those.

The community itself consists of over 30,000 members and there’s no shortage of day-to-day activity. If you like keeping up with the latest broken records, this is one of the best places to do that. The only downside is that while newbies can ask questions, deep discussions tend to be on the sparse side.

To cap off, let’s take a look at a few speedrunners who stream regularly on Twitch. Not only do they run actual attempts live in front of a critical audience, they also show their practice routines and even sometimes teach watchers how to get started with their own speedruns.

When you watch these people, it’s easy to feel the community atmosphere. Of all the gaming subcommunities out there, it’s definitely one of the kindest and least obnoxious that you’ll find.

StingerPA was the guy who convinced me that speedruns could be entertaining. I found him one day when I was searching for a Secret of Mana stream to watch (simply out of nostalgic desire) and ended up losing an hour as I watched him race through areas that I once found so challenging.

Humbling, to say the least.

Perhaps what kept me hooked was the sidebar, where he displays his current progress and how his current run compares to his personal best. Without even realizing, I was cheering for his success. Every setback made me more nervous for him. Within seconds I was invested — almost like we were in it together.

While his main focus rests with Secret of Mana, StingerPA also runs Star Wars: Battlefront II, Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, and Escape Goat 2, though at nowhere near the same frequency.

Gocnak‘s stream is the opposite of StingerPA’s. While the latter is calm, collected, and stoic 100% of the time, Gocnak is quite excitable, loud, and bursting with energy. Neither is inherently good or bad; they just appeal to different kinds of folk.

The background music on his stream, which is an eclectic mix of various electronic genres, adds to the spirited ambience. His channel’s chat is never quiet, and he refers to his network of followers as “Gocnation”.

He mostly speedruns Half-Life 2, though you can also catch him playing other Source-related games, including a couple of beloved surf maps.

Mystakin is a likable fellow with a calm demeanor. His dedication to streaming is evident by his commitment to try at least one speedrun every weekday. And while he’s a self-proclaimed amateur, some of his runs are quite impressive and entertaining.

His game of choice is Shovel Knight, in which he holds the world record for 100% completion. But when he’s not playing Shovel Knight, he’ll be running Super Mario World or Banjo Kazooie, two games that are absolutely perfect for this kind of thing. More recently, he’s been supplementing with a bit of Splatoon as well.

I believe speedrunning is still in its infancy. The past two decades have been an incubation period, slowly cultivating this idea throughout the gaming community. As Games Done Quick holds more and more events, awareness will continue to spread and it will explode in popularity.

In fact, some developers are specifically making games that are designed with speedrunners in mind. The aforementioned Dustforce is one example, but what about the aptly-titled Speedrunners? We can only imagine what else will come out in the next few years.

And as someone who doesn’t speedrun himself, let me tell you: I’m excited. If you want to get involved, check out our four steps to becoming a speedrunner.

What are your thoughts on speedrunning culture? Is it a concept that intrigues you? Or do you think it’s a pointless activity? Where do you see speedrunning going from here? Share with us in the comments below!

Room Escape 100 Walkthrough (Room 100 Walkthrough)

Room Escape 100 Walkthrough (Room 100 Walkthrough) How to Quickly Find Your Lost Mouse Cursor on Every OS

How to Quickly Find Your Lost Mouse Cursor on Every OS Which Games Console Do You Currently Own? [MakeUseOf Poll]

Which Games Console Do You Currently Own? [MakeUseOf Poll] Don't Starve Guide: How to Survive The First Month

Don't Starve Guide: How to Survive The First Month Mad Max: Full Walkthrough for all Missions

Mad Max: Full Walkthrough for all Missions