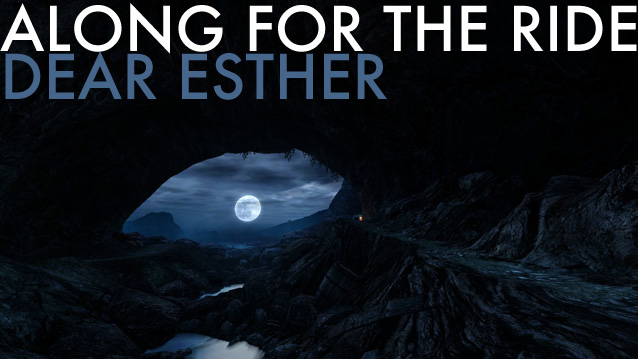

From the articles I’ve read on Dear Esther so far, I think there’s one thing most everyone can agree on: it’s controversial. It’s not controversial in the classically “whoa look at how edgy we are” sense—if you’re looking for dead baby jokes and the like, you’d best look elsewhere. Where it’s most controversial is at its core—people can’t even manage to agree on whether Dear Esther is really a game.

Dear Esther, for those not in the super-exclusive I’ve-Beaten-Dear-Esther club, originated as a Source engine mod released in 2008. It’s been described near-ubiquitously as an “interactive ghost story”, though I feel like “ghost story” is used a bit loosely as the game is not conventionally scary (or conventionally anything) and the apparitions aren’t exactly all up in your grill—in fact, you might have to do a fair bit of looking around to notice the scares at all. During my first play-through, I spotted a single shadowy figure peering out over a cliff in the distance and actually assumed I was just seeing things. My second time around, though, I realized that there were more of them—a whole lot more—and knowing that these things had been there the entire time, whether I noticed them or not, honestly made me a little paranoid.

Dear Esther is designed, from start to finish, so beautifully and thoughtfully that it kinda blows my mind a little bit.With that in mind, let me just say that Dear Esther is one of the most beautiful games I’ve played in a very long time. Not just visually beautiful—though it certainly is that—Dear Esther is designed, from start to finish, so beautifully and thoughtfully that it kinda blows my mind a little bit. The game is largely quiet, but Jessica Curry’s sleepy, tragic soundtrack always seems to kick in at the precise moment the game could use a little mood music. Things are placed where the player will notice them; random objects that serve to clue you in on the mystery, anomalies in the landscape placed at the very edge of your line of vision to lure you in a particular direction. Just as you start to wonder where you’re headed and why, a new piece of narration kicks in with more backstory—albeit occasionally contradictory backstory— to intrigue and befuddle you further. From the very beginning, everything has drawn you towards the radio tower—that familiar red light blinking against an unfamiliar backdrop. In the wise words of Mr. Plinkett, “You may not have noticed, but yer brain did.”

But it’s Dear Esther’s gameplay, not its level design, which calls into question for many the validity of calling it a game. Your only responsibility as the protagonist is to explore, and the only key mappings are your standard WASD and the left mouse button to zoom. There is nothing to win in Dear Esther. You aren’t playing for points and the apparitions don’t do any physical damage. There’s no objective, only a story to tell. This is where people seem to get upset, calling Dear Esther out for calling itself a game when its interactivity is so limited that they believe there could just as easily not be any interactivity at all. I’ve read forum posts where frustrated customers have complained that they spent $10 on a thing that only took them an hour and a half to complete and didn’t make any sense. That’s fair, sort of, although I’d like to ask those people when they last took a trip to a movie theater and if they complained afterwards regarding length over cost. But I understand the sentiment—these people expected a game. Like, a game game, potentially of the shooty clicky variety. They got something quite a bit different, and in their disappointment likely found the whole thing a little pretentious.

But for seemingly every player that found themselves disillusioned with Dear Esther’s gameplay and ambiguous plot, there are a few more who came out of the experience eager to discuss it with others—“What did you see? Did you hear this piece of narration too? Did you see the apparition on the cliff? The paper boats? Morse code?! WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?”—and how often does a video game do that? Dear Esther is an experience that evokes an almost Alternate Reality Game-like response from its fans. As you explore the lifeless Hebridean island, each paragraph of narration exposing your protagonist as slightly more unhinged, distressed and even delusional than you’d previously assumed, it becomes clear that the illusion wouldn’t have worked without the interactivity provided by the Source engine. Lack of choice be damned, Dear Esther couldn’t have been anything other than a game—and with more indie developers creating similarly interactive storytelling experiences, maybe it’s time to expand our definition of the word.

Dear Esther isn’t for everyone. It’s a slow, quiet exploration game with an ambiguous plot, and you’ll find no definitive answers at the end of the rainbow. If you’re looking for a traditional horror game with all the trimmings, probably refrain from dropping ten bucks on this title. Personally, though, I haven’t found a “ghost story” experience so enjoyable and so fun to analyze since before Marble Hornets jumped the shark.

Endless Space: A Review

Endless Space: A Review Dishonored Blueprint Locations Guide

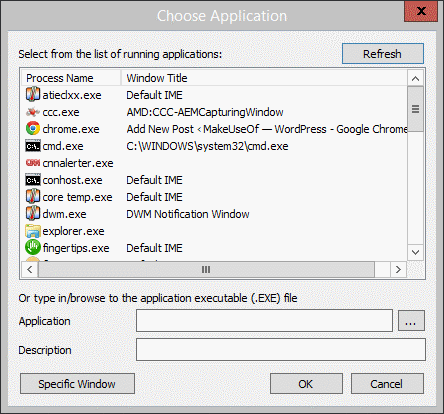

Dishonored Blueprint Locations Guide A Mouse Hack That All League Of Legends Players Should Know About

A Mouse Hack That All League Of Legends Players Should Know About How to take screenshots with PS VITA

How to take screenshots with PS VITA Batman v Superman: Jesse Eisenberg as Lex Luthor

Batman v Superman: Jesse Eisenberg as Lex Luthor