When a new horror-survival game surfaces, gamers climb over each other to be the first to wet their pants in welcome terror. Videos adorn YouTube like so many offerings to the video game gods, and we watch these Let's Plays, reveling in the genuine emotion pulled forth. Gaining internet infamy, playing titles like Amnesia and Slender for any length of time are badges of honor that gamers wear proudly.

At first glance, the question of "Why do gamers like to be scared?" seems easily answered. Horror movies bring in billions of dollars in profit every year, so you might assume that people simply have a taste for a bit of the ol' ultraviolence. However, there is a divide between watching a horror movie and experiencing a horror-survival situation. When a person plays a game, assuming they actually enjoy video games, at some level they are immersed - even an incredibly basic one.

Drawing a gamer into an interactive state affects them much more than if they were to only watch someone playing the same horror game. Typically, first-person titles tend to affect men and women more than third-person perspective. Being in the body of the protagonist is such a powerful point-of-view that developers looking to scare the shit out of players almost have to adopt that perspective, unless they have fantastic camera mechanics, like the original Resident Evil.

Quite a lot goes into the construction of creating a frightening video game. Merely placing a player into an environment with a giant scary monster isn't going to be enough to legitimately terrify your everyday gamer. Looking at titles like Serious Sam, DOOM, and Borderlands, we see fantastically designed enemies, with unsavory and grotesque looks, but the parts don't add up to a survival-horror experience. Whereas many games, like the aforementioned titles, give players a multitude of ammunition, health, defensive abilities, developers looking to really scare their audience seek to instill a sense of urgency and the burden of limitation on the player. That idea includes things like no health pickups, few or sometimes even no weapons, and a lack of information.

As I play Amnesia, I'm struck by how little I want to continue, but my inability to stop. My fear drives me forward, keeping me in a game that has me isolated to a closet, horrified at what I'll see if I open the door. Even with spectators watching me - shaming me into acting like a person who has their wits about them - I am unable to contain my fear as it leaks out of me in cries of terror, gasps, and guttural exhalations.

Being one of those screaming masses, shouting "NOPE.AVI!" at my computer while moving my avatar in the other direction, instead of merely quitting out of the game, I can examine my own reasons for continuing onward. Obviously, I derive some amount of pleasure from being frightened and maybe that is an inherent human need. Bear with me here, I'm about to get very psychoanalytical. In our everyday life, we rarely encounter the bizarre, the horrifying, or anything amounting to actual danger. Exposing ourselves to something different from our routine lives is ostensibly a fulfilling experience. By gripping that emotion with two hands in a situation where control is continually available, gamers are able to wade about in their panic while still seeing straight through the entire encounter.

Many studies have been done by various scientific institutes centering around why people love horror movies and other terrifying thrill-based activities that leave you wondering if you will survive to see tomorrow. Only a few examinations have been made into what makes scary video games so terribly appealing to the masses. Ken Levine has talked about his game-darling Bioshock with NBC News, and how impactful it is to take control of a situation from a director or producer and give that power to a player.

"With a video game, you can't point the camera exactly where you want it to go for exactly how long you want it to go, but you can also have that moment with the player where he's like, 'I don't want to go forward, I'm nervous about going forward,'" Levine said. "And then there's that moment where he actually makes himself go forward anyway. You never have that disconnect where you're shouting at the screen: 'Don't go into that dark room you idiot!' because you're the idiot walking into the dark room."

In another dark - but crowded - room, full of my friends, I witnessed a group-attempt at Slender. Shouting at the player, we added to the suspense, but ultimately didn't feel nearly as affected by the experience as the person currently running about. As we collected pages, with Slender Man drawing closer, shrieks of "He's right behind you, don't turn around! Don't turn around!" began filling the room, sending the player into a panicked state of immobilization. After turns had been distributed and everyone knew what it was like to run from Slender Man, one of my friends commented that the game was much more frightening when you were in control, but simply watching took a significant step back from the terror.

Whatever rationalization you choose to justify turning down the lights and snuggling up with an insomnia-inducing game, the bottom line is that horror-survival titles pick at the corners of our brain we rarely get to explore. Tapping into fear, developers are giving gamers an experience that can only be replicated in a "Haunted House" where real people jump out at you from behind corners wielding chainsaws with no chains. Am I even making sense anymore? We play these games because the experience is novel and something we have never - and will never - become accustomed to.

Batman: Arkham Knight Costumes Guide: How and Where To Get All Costumes/Skins For Batman, Nightwing and Robin

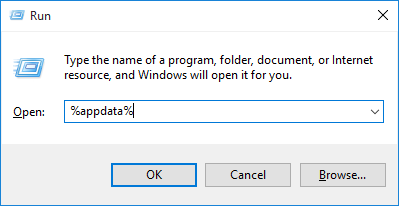

Batman: Arkham Knight Costumes Guide: How and Where To Get All Costumes/Skins For Batman, Nightwing and Robin 13 Run Shortcut Tricks Every Windows User Should Know

13 Run Shortcut Tricks Every Windows User Should Know Killing Floor 2 (PC) Monster Guide

Killing Floor 2 (PC) Monster Guide Serious Sam Double D XXL Review: A New Definition of Six Gun

Serious Sam Double D XXL Review: A New Definition of Six Gun Gears Of War 3: Secrets & Easter Eggs Revealed

Gears Of War 3: Secrets & Easter Eggs Revealed