The BioShock series is something that, despite its many failings is altogether special. Since its inception in the early years of this generation, the BioShock series has attempted to bring greater standards to AAA video game narrative. Each of them openly billed as a sort of interactive treatise on political philosophy, the three games have been the study of much debate and rather harsh scrutiny, and have largely failed to realize their own legacy.

BioShock Infinite, hampered by little more than a few pacing issues and unnecessary violence, layers it’s carefully crafted story with themes of prejudice, revolution, redemption, unconditional love and the innate curiosity of humankind. After nearly six years, Infinite finally fulfills the once-empty lofty promises of its predecessors.

Violence, prejudiced attitudes, and righteous zeal for imperfect idols might very well be the most recurrent of our species’ sins. One hundred years ago, the western world was steeped in goose-stepping jingoist propaganda and the most basic extension of human rights to non-whites and non-males. At the heart of second wave of European and American colonization, BioShock Infinite is intentionally set in one of the most politically tumultuous times in modern history, providing the seeds for a conversation about issues we continue to face globally.

Infinite explores these ideological vestiges through the eyes of the player-controlled protagonist, Booker DeWitt. A down-on-his-luck gambler, Booker is offered the chance to wipe away his debts, by retrieving a woman locked in a tower. While this may sound like it was taken from the list of clichéd, groan-plots, and a surefire set-up for a damsel in distress, the reality is something far different.

Elizabeth, the aforementioned Princess Peach stand-in, is easily one of the best realized characters in the gaming pantheon. Affecting, intelligent and more than capable of taking care of herself, she is not a love-interest, nor is her role incidental to the plot.

Interactions between Booker and Elizabeth are brilliantly poignant. Watching the pair explore together yield calm, intimate moments that are some of the more natural and affecting that have ever been seen in games. These brief glimpses into their pasts, their thoughts and their dreams allow a more dynamic, gradual construction of character that transcends some of the more tired storytelling methods on which video games have traditionally relied.

The stage for the waltz of Elizabeth and Booker is the flying city of Columbia. Like Rapture before it, Columbia is very much a character on its own. Its aesthetics and inhabitants are one of the more incredible executions, and it calls to a sense of wonder and majesty that is so rare in a modern era nearly devoid of classical myth.

Set against the political whims of Columbia’s many factions, Elizabeth and Booker fight their way through, across, over and several districts of the city. As the Infinite progresses, the city descends into chaos as its political actors move to tear one another apart. As the perpetual center of everyone’s collective attention, the ill-starred pair is constantly beset by the violent tendencies of revolutionaries and unlikely lawmen. While that conflict assures a base level of tension, it’s also the cause of the game’s single weakest link – pacing.

Sadly, BioShock Infinite falls into some of the more tedious habits of big-budget games. Endless waves of murderous baddies can be fun, but without a break, without any calm segments to contrast with the action, those scenes lack context. Thankfully, these issues really only come up in the middle half of the game. Acts One and Three are nothing if not spectacular, and balance metered sentimentality with permissive bloodlust. As a rather stark contrast to its predecessors, the real narrative weight of Infinite is generally unhindered by its unnecessary level of violence.

When that time does come, however, Columbia’s unusual origin provides plenty of unique options for combat and more tactical approaches. Vigors for example, replace the plasmids of the first two BioShock games. They do, however, offer very similar effects. Launching bolts of lighting, setting baddies on fire, and manipulating the minds of others are all when the appropriate tonic is found and consumed. Powering these abilities requires salts, preventing their overuse.

Connecting each of the major districts of the city are “SkyLines”. Within the context of the Infinite world itself these light rails are used to transport goods and supplies between disparate areas, but you can co-opt them to move combat into a dynamic, three-dimensional space. Freight hooks, scattered across the city provide similar albeit more limited opportunities.

Connecting each of the major districts of the city are “SkyLines”. Within the context of the Infinite world itself these light rails are used to transport goods and supplies between disparate areas, but you can co-opt them to move combat into a dynamic, three-dimensional space. Freight hooks, scattered across the city provide similar albeit more limited opportunities.

Elizabeth too plays a vital role in the anarchic battlefield. Canonically, she has the ability to open and access dimensional rifts known as “tears”. In combat, these tears can be used to bring in extra supplies, cover or freight hooks. Periodically, she’ll also toss booker health packs, ammo and salts. She becomes a consistent companion, not unlike Half-Life 2’s Alyx Vance.

Columbia’s greatest triumphs are rooted in its pervasive, meticulously designed atmosphere. The city genuinely feels like a chunk of Victorian America has been lifted into the sky. Its people are skeptical of the changing world. Some fight against the emerging concerns of labor laws, of women’s rights, and of racial integration. All the while, voyeuristic glimpses of the underclasses yield telling clues of fomenting dissent.

Columbia never ceases to feel real. A far cry from the 1960s, pseudo steampunk parade of Rapture, the early 1900s barely has anything that citizens of the information age would call “technology”, beyond the fantastical automata and, of course Columbia itself. Audiologs are presented as self-contained phonographs, when not speaking in person, people primarily communicate through telegraph, and electricity is still an exciting unknown for most.

The people that inhabit this strange, alternate-reality fiction take everything as given. Their honesty and transparency are brought to life by one of the best vocal casts I think I’ve ever seen. Troy Baker (Booker), Courtnee Draper (Elizabeth) and countless others give absolutely inspired performances with perhaps one or two missteps across the entire fifteen hour adventure.

This is the kind of the game that begs to be analyzed, that loves the years of attention and scrutiny it will inevitably receive. Thankfully, Infinite does everything it can to earn that critical diligence. Drawing upon questions that are universally applicable and particularly resonant in an era where society is struggling to redefine itself in the face of countless centuries of discrimination, Infinite is a product of the society from which it is born.

There are so few games that ever seem to attempt to be something more. BioShock Infinite is one of them. Provided that excessive violence isn’t a complete turn-off, this is not a game that you should miss.

Ni No Kuni 2 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game .

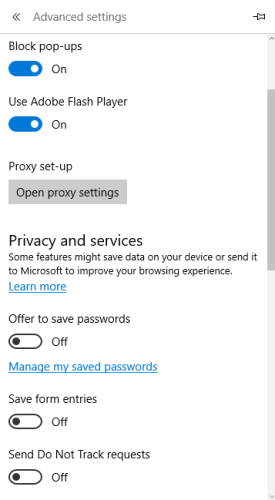

Ni No Kuni 2 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game . A Microsoft Edge Review From A Die-Hard Chrome User

A Microsoft Edge Review From A Die-Hard Chrome User The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt PS4 Pro Tip: Hold Sensor Bar To Open Inventory & Swip To Open Map, How To Reduce Horse Fear Level: Updated

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt PS4 Pro Tip: Hold Sensor Bar To Open Inventory & Swip To Open Map, How To Reduce Horse Fear Level: Updated Sleeping Dogs: The Zodiac Tournament Walkthrough

Sleeping Dogs: The Zodiac Tournament Walkthrough How to do Borderlands The Pre-Sequel Research And Development Side Quests

How to do Borderlands The Pre-Sequel Research And Development Side Quests