In Minecraft, the relationship between redstone dust and redstone torches is elegant in its simplicity because you can make so many different machines by simply combining these two items with blocks — however, redstone repeaters make the work a lot easier.

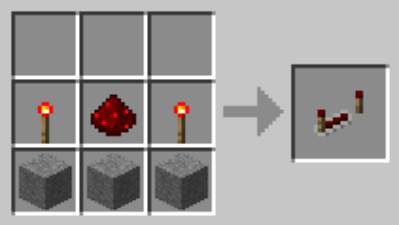

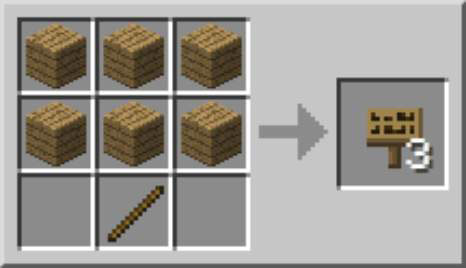

Repeaters are small and versatile and highly necessary for efficient and compact designs, but they’re also a bit more difficult to craft than simple redstone items. A single repeater requires the following items:

Two redstone torches

A lump of redstone dust

Three blocks of smooth stone (obtained by smelting cobblestone blocks in a furnace)

A redstone repeater is a gray panel that can be placed on most standard blocks. Repeaters, unlike dust and torches, cannot be powered from any side: They can be charged only from the back, and they can transfer charge only to the front.

The triangular indentation on top indicates the direction of the charge; power is translated from the wide end of the triangle to the tip. When you place a repeater, the output end faces away from you.

The repeater also contains two small redstone torches on its top. The first torch is at the vertex of the triangle, and the second is placed on a slider behind it. You can adjust the second torch’s position on the slider by using the Use Item button (which is, by default, the right mouse button).

The farther apart the two torches are, the longer it takes for the repeater to update its output when the input changes. This delay time can be one, two, three, or four times that of a normal redstone torch. Basically, repeaters take the input behind them, delay for a moment, and then copy the input in front.

A few properties of redstone repeaters make them individually useful:

Repeaters are adjustable timers. For example, if one branch of a circuit is slightly faster than another, you can put in a repeater to ensure that the branches are aligned. You can also string together lots of repeaters to delay a circuit for a longer period.

Repeaters fit well with other mechanisms. Redstone dust can be tricky, because it automatically connects with mechanisms around it. Repeaters don’t have this problem: Because repeaters have only one way to receive and produce power, they function only when you want them to.

Repeaters are powerful. Current can travel 15 blocks after leaving a repeater. If you want to extend a wire of redstone, all you have to do is place repeaters at 15-block intervals for the wire to run quickly and smoothly. Also, if a powered repeater faces a solid block directly adjacent to it, all mechanisms adjacent to that block are powered. This is the simplest way to power blocks.

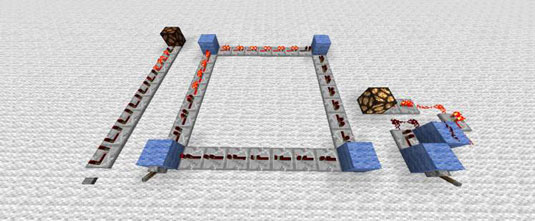

Here are three simple ways that you can apply redstone repeaters in a circuit. You can see a repeater-based timer, a width of current that travels in a loop, and a little example of how compact repeater-based designs can become.

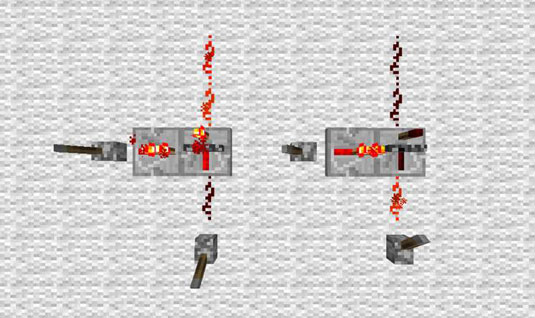

The redstone repeater also has an interesting secondary function, which requires two repeaters to accomplish. If you place a redstone repeater in such a way that it connects directly into the side of an adjacent repeater, you can power the first repeater to lock the second.

A locked repeater cannot change its state. Regardless of input, a powered, locked repeater stays powered, and an unpowered locked repeater stays unpowered, until the repeater is unlocked — it unlocks automatically when the locking repeater is no longer powered.

Each north-facing repeater was set to its current state and then locked, thus acting regardless of its input. The gray bar across a repeater indicates that it’s locked.

The ability to lock redstone repeaters is useful for making circuits that can be halted with a shutoff switch — just put a repeater at the end and add a lever that locks it when activated. Of course, like all redstone properties, it can be applied in many other ways. For example, a locked repeater’s charge cannot be tampered with unless the locking device is shut off first.

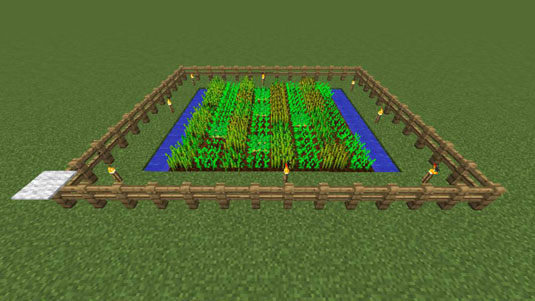

How to Grow Crops in Minecraft - For Dummies

How to Grow Crops in Minecraft - For Dummies How to Apply Dye to Minecraft Items - For Dummies

How to Apply Dye to Minecraft Items - For Dummies How to Plan and Assemble a Minecraft Minigame - For Dummies

How to Plan and Assemble a Minecraft Minigame - For Dummies How to Message Minecraft Players with Signs and Banners - For Dummies

How to Message Minecraft Players with Signs and Banners - For Dummies Minecrafts Medium Biomes - For Dummies

Minecrafts Medium Biomes - For Dummies