Minigames are complex and interesting redstone devices that allow the Minecraftplayer to complete a simple challenge. These minigames can be ones of your own invention, though many builders like to imitate classic board games or arcade games in Minecraft.

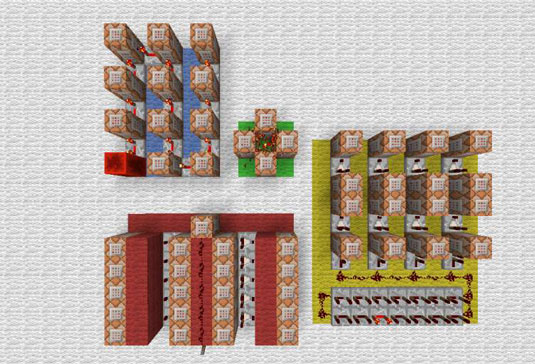

For example, check out this re-creation of a classic game: Place the objects in the correct slots within a time limit. When players press the button to start the game, they’re given 16 different colors of wool blocks and must throw them into the corresponding hoppers before TNT destroys the platform.

This minigame is relatively small, in programming terms, but as with all machines, you need to understand its primary inputs and outputs in order to build it. This list describes the components of this minigame:

A button that starts a timer and provides the player with wool blocks: Command blocks were used for the wool, but dispensers work as well.

A set of hoppers that accepts wool of certain colors and can tell when a single extra block is added to its storage space. Each hopper on the platform has a second one underneath it, filled with wool of a particular color (so that only wool of this sort can be filtered into it).

A system that checks the contents of every hopper after the timer runs out. Because there is little room to work with the actual programming, the engineer must use an alternative form of redstone engineering for this task: minecart tracks. After the timer goes off, TNT minecarts are sent down each of the four tracks and explode only if the player has lost.

Thus, for each hopper that is filled, some booster rails are powered and an activator rail is depowered — if all hoppers are filled, the minecarts pass through harmlessly. This combination of minecart tracks and redstone dust allows you to program in a small space without letting the code interfere with itself.

This example shows the process behind designing a minigame. When you create your own minigame, apply these tips:

Remember what information must be stored in the game. For example, the game of tic-tac-toe uses nine squares to accept three values (X, O, or blank). In Pong, the game must know the position of the paddles, the scores on each side, and the position and direction of the ball.

These values can be recorded by using entities such as players and minecarts, scoreboard objectives, or huge clusters of memory latches. Just be sure to use a method that can connect smoothly with the rest of your game. This is entirely possible — veteran Minecraft designers have built these games and much more with redstone and command blocks.

Connect the player’s input to this information. Think about how each player’s actions change the game, from flipping levers to defeating enemies. The player must somehow be able to make his moves, adjust his pieces, and play some part in winning the game. Thus, at least some of your game’s stored information has to be hooked up to whichever devices are under the player’s control.

Attach the stored information to an output, which updates when needed. For example, if you have a variable that tells you whether a level is complete, you should connect the variable to a device that advances the level when powered.

How to Obtain, Program and Activate a Command Block in Minecraft - For Dummies

How to Obtain, Program and Activate a Command Block in Minecraft - For Dummies How to Plan and Assemble a Minecraft Minigame - For Dummies

How to Plan and Assemble a Minecraft Minigame - For Dummies Minecraft Modding: How to Add Effects to Your Spleef Game - For Dummies

Minecraft Modding: How to Add Effects to Your Spleef Game - For Dummies How to Make and Use Redstone Torches in Minecraft - For Dummies

How to Make and Use Redstone Torches in Minecraft - For Dummies How to Add Levels to Your Minecraft Construction - For Dummies

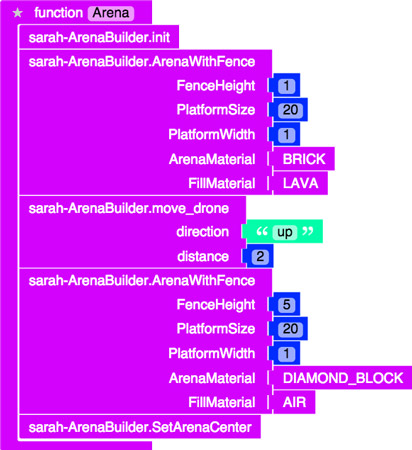

How to Add Levels to Your Minecraft Construction - For Dummies