Sometimes it feels like every video game wants to be an RPG. Racing games insist you level up your cars. Shooters want you to level up guns. You Must Build A Boat is a tile-matching puzzle game with dungeon-running thrown in that cheekily insists I level up a boat I happen to have. No reason’s given why I have a boat, and after each upgrade at precisely the moment I think “Why am I doing this?” it screams the answer in words that slam into the screen one by one: You. Must. Build. A. Boat.

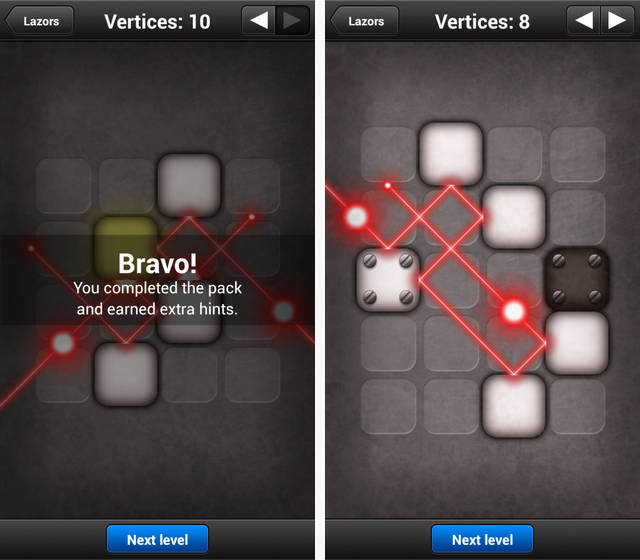

If the phrase “tile-matching puzzle game with dungeon-running thrown in” sounds familiar, you might have played EightyEight Games’ previous creation, 10,000,000. A popular mobile game that later came to PC, it gave you a grid of icons to play match-3 with while an adventurer ran through a dungeon at the top of the screen. When the adventurer came to a monster you had to slide rows and columns to match swords or staves for an attack; when a treasure chest appeared you needed to match keys to open it. Meanwhile, the edge of the screen was creeping closer to that adventurer’s back and if you took too long–or got hit too often–it caught up and the round ended.

You Must Build A Boat repeats the formula almost exactly, although with just enough tweaks that the original now feels like it’s missing something. Now it’s possible to continue making matches while new tiles slide into place, increasing the pace. Traps are another new addition, hovering toward you like drones, holding an icon you need to match before they arrive and forcing you to waste a matched set. There are still crates to match with a chance an item will pop out–scrolls with one-shot spells, a bow that drops a magic arrow on one enemy’s head like a nuke–but instead of those items being kept in an inventory at the top of the screen, now they float in the grid. They’re harder to forget about but until you use them they take up precious room.

The most significant new addition is the boat. Achieve a quest objective and the boat grows, perhaps adding a smithy or gymnasium or a monster who joins your crew and adds a small bonus to your stats. While the pixel art doesn’t do much to differentiate them–a zombie looks much like an orc in You Must Build A Boat–they nevertheless add personality. I assume they’re hanging out on my party yacht playing shuffleboard and drinking abusively while we’re sailing from dungeon to dungeon.

I say ‘sailing’ but what actually happens is the crew all jump up and down, which seems to propel the craft through the water somehow. It’s one of dozens of small, completely unnecessary touches that add joy to You Must Build A Boat. The sound of shattering glass accompanies each match; captured monsters burst out of a box marked “DANGER”. Upgrading my sword involves clicking a bunch of times to make a bar fill up, but as I do I hear a hammer smacking away at a forge. I’m not clicking a mouse, I’m a burly blacksmith working hot steel! It’s delightful.

Sometimes I wonder if I’m the one being played.

All that delight does cover up something slightly sinister. Like all games about watching numbers go up, sometimes I wonder if I’m the one being played. Each round of You Must Build A Boat is short, but I always get at least a bit of gold, or some of the other resources necessary to keep my aquatic menagerie growing. I keep wanting to go back for more in the same way I always want another cookie, and that’s an impulse I distrust. It’s not a feeling unique to this game, but it’s there and it’s dragged me back for so many hours I experienced a version of the Tetris Effect–when everything in your house starts to seem like it belongs at one end, lined up in neat rows.

But I can’t entirely hold that against You Must Build A Boat, because there are so many details to appreciate. When you get booted out of a dungeon it says ‘You Win!’ no matter how badly you did. Your loot is as likely to be tuna, shampoo, and a pencil as precious gemstones. The Hammerhorn summons your crewmonsters to your defense, leaping across the screen in a blur of pixelbeasts. There’s a green-haired guy named Woodward who looks after your library and gives advice on the weaknesses and specifics of each new monster type, which is often hilariously useless. “Monster analysis: Orc – green.” Thanks, Woodward. The mathematics behind it may feel manipulative, but all these touches are so gosh-darn nice I happily forgive it.

SimCity Previewed: A Sandbox for City Builders

SimCity Previewed: A Sandbox for City Builders Batman Arkham Knight: take on Firefly and put out the fires

Batman Arkham Knight: take on Firefly and put out the fires How to add Custom Character portraits in Shadowrun: Hong Kong

How to add Custom Character portraits in Shadowrun: Hong Kong Japan Adventure Walkthrough Guide

Japan Adventure Walkthrough Guide CEO Fraud: This Scam Will Get You Fired & Cost Your Boss Money

CEO Fraud: This Scam Will Get You Fired & Cost Your Boss Money