We’ve talked a lot in the past about how companies use social media to track you and how governments could be watching you on Facebook. But there’s another group that’s also watching, analyzing, and capitalizing on every move you make on social media: political campaigns.

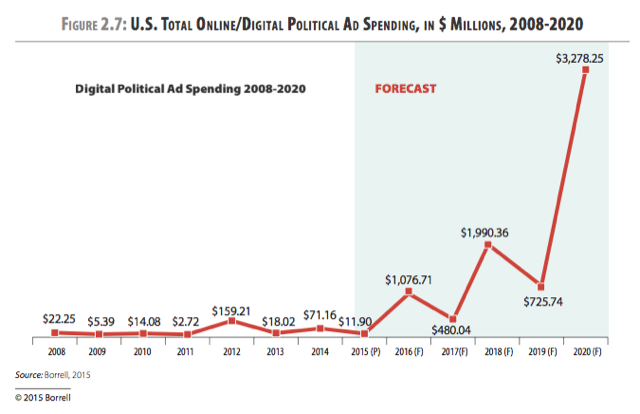

Many people are predicting that spending on online ads by campaigns will break the $1 billion mark before the 2016 US election is over. Campaigns start almost two years before a presidential election, making political campaigning a huge industry in the US. Which, of course, means there’s a lot of money at stake.

Political advertisers have a strong incentive to use highly targeted ads to get the most out of every dollar spent by a campaign. How do they accomplish this targeting? In many cases, via social media sites. Ralph Legnini, the lead political advertising strategist at DragonSearch Marketing, puts it like this:

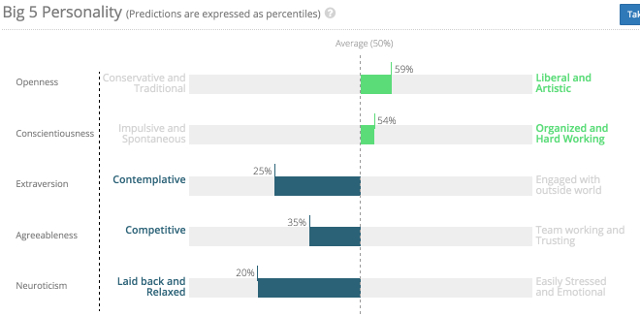

[T]he social media platforms – particularly Facebook – offers very granular targeting options. They have profiled everything about everyone and they know if you cry when someone’s dog dies, or if you support gay marriages, how lucrative your paycheck is, and what political views you have, and causes you support.

He also told me in an email that these data points are like “palettes of color for a painter”; they allow a strategist to build an advertising campaign that targets a narrow range of people with a specific set of ads. Just as a painter benefits from having a wide range of colors available, so a strategist benefits from a wide range of data points.

The types of data that can be used to target political ads are wide-ranging. Campaigns often start by uploading a list of specific users, like those who attended a rally, signed up for a candidate’s newsletter, officially joined a party, or have donated money to the campaign in the past. These people are the easiest to target, as they’ve already shared their information with the campaign.

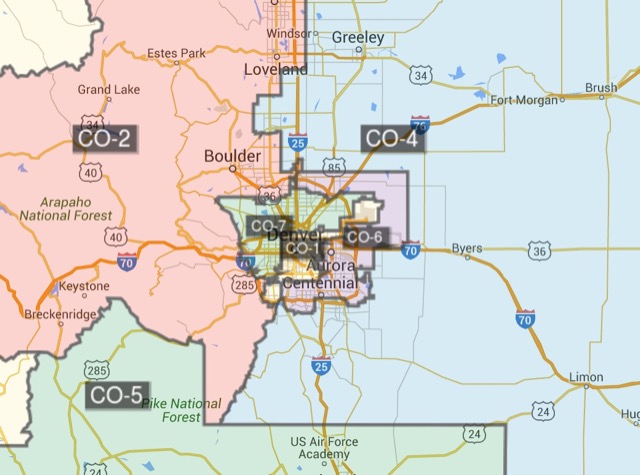

More information can come from voting records; Legnini gives an example of targeting ads to Democratic women in a specific New York voting district, city, and ZIP code that have voted in the last three elections (who you voted for in an election is private, but whether or not you voted, and whether you requested a mail-in ballot, is public record).

How might an agency go about targeting Democratic women when the only thing on record is whether they voted? Easy: get that information from Facebook. The social network knows a lot about you from what you post, which pages and ads you click on, who you’re friends with, and pretty much everything else you do online.

It knows where you live, which politicians you’ve posted about, your marital status, your age and gender, events you’ve been to, books you’ve read, major life events, products you’ve purchased, and a whole host of other things. And all of these pieces of information are extremely valuable to advertisers.

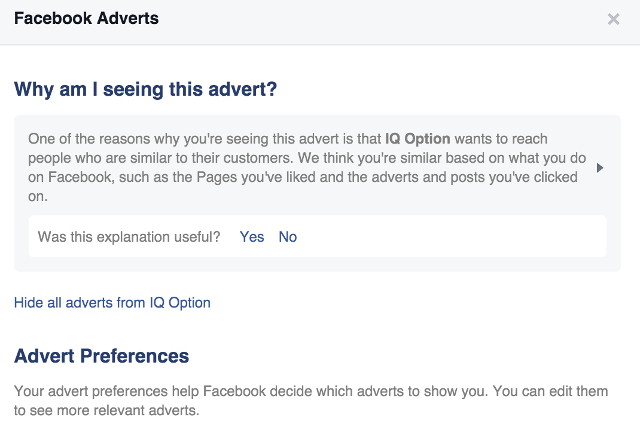

All of this information is analyzed to form an overall picture of you, and advertisers can take advantage of this, too, says Erik Hawkins, the head of Facebook’s political sales, in an interview with NPR. After uploading a list of users, Facebook can create a list of similar people that can also be targeted with ads.

The identities of these users are kept private, but this service allows advertisers to significantly expand their reach to specific types of people. Exactly how Facebook determines that you’re “similar” is unknown, but they say it has to do with the pages you like and the ads and posts you’ve clicked on.

Ken Dawson, head of digital strategies for Ben Carson’s campaign, told NPR that “We can target [users] around how many ads we want to serve them, how often we want to serve them and then build calls to action around those ads.” Those calls to action, of course, are also tailored to the types of people that are being targeted by the ads.

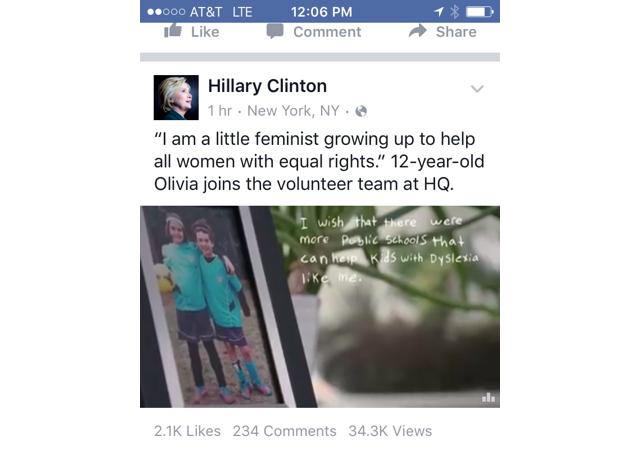

For example, some ads could be served to diehard supporters of a particular party or candidate, encouraging them to call their friends or local representatives, while others will be delivered to undecided voters presenting them with issues that could be relevant to people in their particular income tax bracket—many of them, such as the one below, also appeal to specific emotions and ideals.

The ads are often directed to specific landing pages, says Legnini, that expand on the messaging in the ad. “If you can show that other folks just like those you are directly targeting have already pledged support for your candidate and explain why – then in my experience, you can definitely sway votes that you would not typically get.”

Of course, like any other segment of advertising, political advertising contains a wide variety of different media; images, written content, videos, interviews, petitions, infographics, statistics . . . they’re all used by different campaigns on Facebook, and each is targeted specifically to a group of people that have been determined to be likely to respond to that type of information.

The idea of the “echo chamber” has been gaining traction over the past years as we become more and more adept at filtering out things we don’t agree with online. Whether that’s unfriending Facebook friends that have different political views, finding news sites that only publish stories we already agree with, or unconsciously being influenced by Google, people are often insulating themselves from new ideas. And I was immediately worried about this when I started reading about political ad targeting.

I asked Legnini whether the type of targeting that we’ve seen in recent year runs the risk of making the issue worse by showing lots of conservative ads to conservatives and liberal ads to liberals. He wasn’t worried, though, and gave me an example of a campaign that he ran in which many people were swayed from one party to another largely due to the “creative and aggressive” social advertising campaign that he created.

“[T]he degree in which you would try to sway voters who might be on the other side of an issue is dependent upon the individual election and candidate,” he said, which makes a lot of sense. Of course, different advertisers and different campaigns use a lot of different strategies with information—some will try to fan the flames of their diehard supporters, others will aggressively target the middle of the spectrum, and many will use a mix of the two.

Of course, even if reinforcing the echo chamber isn’t an issue, there’s still the issue of trusting what you read online: campaigns are going to show you information that they think will make you more likely to vote for their candidate, not necessarily information that presents both sides of the argument fairly.

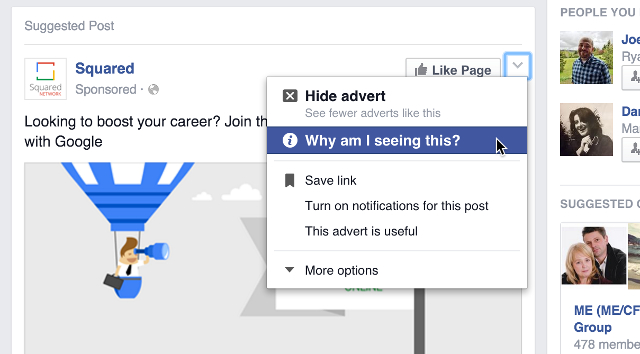

Fact-checking websites can be a hugely valuable resource around this time of the election cycle, and Facebook’s “Why am I seeing this?” feature can also clue you into how a specific ad is trying to take advantage of your emotions or history, so be sure to make use of both of those.

Spend time learning more about candidates in the election, too, so you can see through any potential misinformation. Use sites like ISideWith.com to see whose views you probably agree with. Pay attention to what you’re seeing, think critically, and be open to new ideas. If you can do those things, you’ll not only better understand political advertising, but you might even benefit from it!

What do you think about political advertising on Facebook? Are you okay with the amount of information on you that ad agencies can buy from social networks? Or do you feel like you’re being taken advantage of? Share your thoughts below!

Image credits: Borrell, GovTrack, PathDoc via Shutterstock.com,

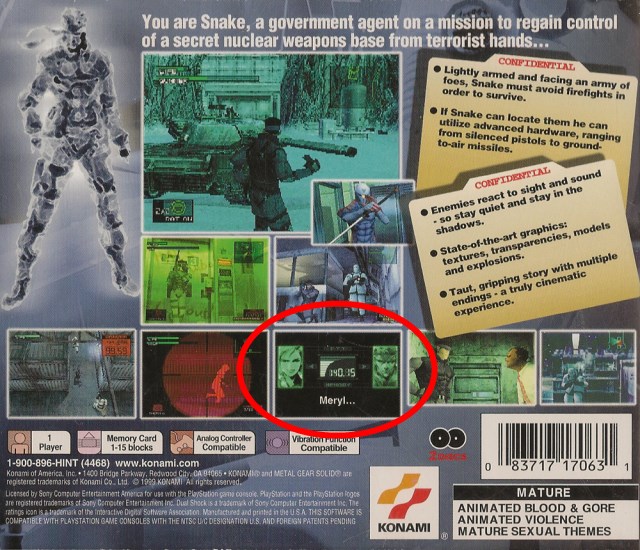

3 PlayStation Games That Made Us Look At Video Games Differently

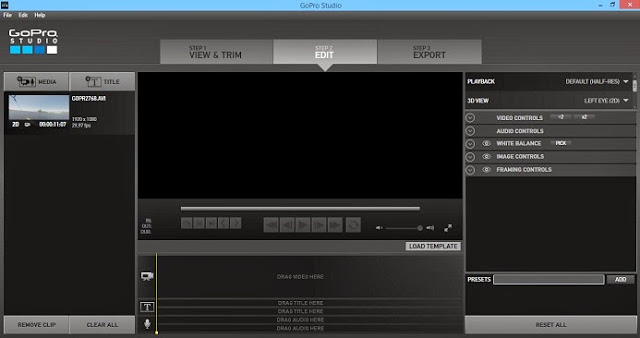

3 PlayStation Games That Made Us Look At Video Games Differently Produce panoramic photos using a GoPro Hero 3

Produce panoramic photos using a GoPro Hero 3 Assassin's Creed Unity Outfits Guide: How To Unlock Altair, Ezio, And Other Assassin's Outfits For Arno

Assassin's Creed Unity Outfits Guide: How To Unlock Altair, Ezio, And Other Assassin's Outfits For Arno 3 Cat and the Forty Thieves Walkthrough

3 Cat and the Forty Thieves Walkthrough Wasteland 2 Wiki: Everything you need to know about the game .

Wasteland 2 Wiki: Everything you need to know about the game .