Like all of the best science fiction shows, Doctor Who has taken modern conveniences and politics, and expanded them into feral beasts with the audience in their maws.

It’s now been over a decade since Doctor Who was revived, but the show itself is well over 50 years old. That’s over 50 years when new technology was popping up all over the shop.

Let us take you on a journey through time with the Doctor to see how this little British show has charted our fear of new technology over the course of five decades and counting.

The series established the idea of the alien in the everyday very early on: nestled in an ordinary junkyard, we first came across the TARDIS, a living time-space ship that’s bigger on the inside than it looks on the outside.

But it took a surprisingly long time for the production team to tackle “modern” technology. In fact, apart from the debut episode, An Unearthly Child, the first full tale set in contemporary London was 1966’s The War Machines.

Amid the Swinging Sixties, the Post Office (now BT) Tower loomed, the tallest building in the city, a fresh addition to the skyline since the TARDIS last materialised there. Of course telecommunications were nothing new – Alexander Graham Bell having first using the telephone in 1876 (a moment partially relived in 2005’s Father’s Day) – but this visual symbol of our interconnectivity inspired Doctor Who‘s resident scientist, Kit Pedler, and writer, Ian Stuart Black, to dream up WOTAN.

That’s the Will Operating Thought ANalogue, essentially a living supercomputer. Just in case you didn’t know.

The War Machines wasn’t simply a story of an artificial intelligence, however. When the Doctor arrives, there are just four days left until it’s linked to military computers across the world, further hypnotizing Londoners into constructing simpler mobile computers: the titular War Machines.

As the world grew ever more connected through technology, the production team realised that it could be a strategic weakness. The concept mulled over the idea of centralized computing, a result of a supercomputer introduced in the early 1960s. The CDC 6600, released in 1964, was the fastest in the world. This was the same year the Post Office Tower was completed.

Interconnectivity was later explored once more in The Invasion (1968), with International Electromatics acting as a front for the Cybermen, who attempted to control the world using radio transceivers.

Created by Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis just five episodes after The War Machines, the Cybermen famously came from early concerns over organ transplants; perhaps to some, the prospect was something out of Frankenstein, particularly before the availability of immunosuppressant drugs, especially cyclosporine, in 1983. Mary Shelley’s novel, one of a handful of banned books all geeks should read certainly informed 1976’s The Brain of Morbius, which questioned transplantation going too far.

Pedler and Davis specialized in speculative science, so foresaw a time when even the natural life of organs would be prolonged by technology – and also replaced entirely. In 1966’s The Tenth Planet, flesh aspects lingered with the Cybermen, despite certain “weaknesses” being removed; the following year, the first heart transplant took place, while the use of pacemakers grew even more widespread.

The Tenth Planet was also Hartnell’s last regular serial as the First Doctor, so in effect, his whole body was transplanted on screen by that of Patrick Troughton’s Second Doctor.

Across the Second Doctor’s tenure, the Cybermen proved an ongoing threat, each time being replaced to a greater extent by technology.

Interestingly, The Moonbase (1967), the second story involving the Cybermen, saw a time when the human race had established a regular outpost on the Moon, acting as a weather “control hub”. This was obviously before Apollo 11’s historic mission – as was The Seeds of Death (airing January to March 1969), incredibly foreseeing a time when we had got bored of space travel.

The late 1960s were arguably the Cybermen’s heyday, but the conceit behind them permeated throughout the following decade. Notably, the unsettling uncanny valley is exploited in the Fourth Doctor era.

In Tom Baker’s debut story, Robot (1974), Professor Kettlewell grew emotionally attached to his metallic creation, while The Invisible Enemy (1977) gave us the lovable robotic companion, K9. But these friendly visages were consistency undermined: K9 was obviously deadly, while the Robot was used by evil would-be usurpers.

The message seemed to be to not get too attached to the machines, drawing direct correlation between our emotions and the robots’ lack of feelings.

In The Robots of Death (1977), we’re treated to an Agatha Christie-inspired murder-mystery, carried out by a series of eerie “Dums,” “Vocs,” and “Supervocs” – the machine class system imposed by humanity. It’s perhaps telling that a supposedly-mute Dum is, in fact, undercover and so isn’t as “dumb” as it may appear.

We also see an example of robophobia, described by the Doctor as “an unreasoning dread of robots. You see, most living creatures use non-verbal signals. Body movement, eye contact, facial expression, that sort of thing… While these robots are humanoid, presumably for aesthetic reasons, they give no signals. It’s like being surrounded by walking, talking dead men.”

These robots are, however, being corrupted by Taren Capel, a scientist raised by robots who wants their freedom. Outside influences affecting machines is a common theme in science fiction – generally fighting against Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics – and in the previous tale, The Face of Evil¸ it’s actually the Doctor who gives an artificial intelligence a split personality. Once his mind is eased from Xoanon, the supercomputer gives up its God complex and returns to sanity.

The Android Invasion (1975) presents us with untrustworthy duplicates of familiar faces, including the Doctor’s companions, Sarah Jane Smith and Harry Sullivan, but the next time androids appear, it’s more of a romp. The Androids of Tara (1978) is an upbeat retelling of the 1894 novel, The Prisoner of Zenda by Anthony Hope, both considering the political ramifications of doppelgangers.

That’s not to say the Third Doctor era lacked threats from technology: fans typically remember The Green Death (1973) for its giant maggots and its touching farewell to popular companion, Jo Grant, but it’s the Biomorphic Organisational Systems Supervisor (BOSS) that reveals a production crew rallying against authority figures.

The Doctor is of course exactly that, but the Doctor Who team were more troubled by corrupt elements, egotists who think they know what’s good for society. This was more a political commentary than an attack on technology, but they demonstrated a machine’s power over humanity in The Mind of Evil (1971).

Except the Keller Machine actually contained a living Mind Parasite, feeding off negative emotions.

Doctor Who in the 1970s seemed intent on teaching us not to trust machines. They can aid us, and even look like us, but something sinister lurks within. That emotional connection that we subconsciously attach to inanimate objects weakens us.

The notion is largely forgotten about during the 1980s, although some tales still warn viewers about how technology can be used to manipulate us.

In particular, the show turns its eye on television itself. Vengeance on Varos (1985) tells of a society hooked on interactive TV. Political prisoners are tortured live on television, subject to the public’s whimsical voting. It’s like American Idol, but not quite as painful to watch.

It cautions us about how easily we can be dehumanized, how empathy can be lost when staring mindlessly at the so-called “idiot’s lantern.” Reality television might seem a relatively new concept, but shows like Candid Camera had been running since 1947 on radio and 1948 on TV, and similar shows were on the increase in the UK.

At the conclusion of Part One of Vengeance on Varos, both real-life viewers and those on Varos were tricked into believing the Sixth Doctor was dead. That manipulation continued in The Happiness Patrol (1988), which showed a perfect civilization where everyone is happy – because anyone who wasn’t happy simply disappeared. Once more, this seems like an overt political statement, but the illusion of a care-free society is relevant to how parties can twist media.

Interestingly, when the show returned in 2005, media manipulation remained a big issue. The Long Games aw the human race controlled by the output of broadcaster, Satellite 5. As The Editor notes, “The right word in the right broadcast repeated often enough can destabilize an economy, invent an enemy, change a vote.”

2015’s Sleep No More, too, toyed with the same notion: after much subterfuge, a seemingly-electrical threat, the Sandmen, were revealed as being behind the recording. Presented as a “found footage” tale, with no incidental music or proper title sequence, the whole idea was that the Morpheus signal that manifests the Sandmen is transmitted through the episode, so anyone who sees the tape would carry the creature.

Andrew Cartmel (script editor, 1987-1989) was a fan of sci-fi in general and especially the Cyberpunk movement, considering that technology would result in a dystopia rather than the glittering futuristic cities in the sky envisioned by many fantasy writers.

With writer, Ben Aaronovitch, a well-worn – but nevertheless pertinent – trope was reintroduced: Battlefield (1989) blurred the lines between technology and magic. After all, technology from the future would look like wizardry. The Doctor was fashioned into Merlin from the Arthurian Legend.

After the show’s cancellation in 1989, the following 15 years was a terrible time for Doctor Who, the 1996 TV movie providing an oasis in a bleak desert. The 90-minute film, a British-American-Canadian co-production, saw Sylvester McCoy’s Seventh Doctor regenerate into Paul McGann’s Eighth Doctor. His arch-enemy, the Master (Eric Roberts), provided suitable menace to proceedings.

True to form, Doctor Who looked to the future, envisioning a problem at the turn of the Millennium. The TARDIS’ power supply, the Eye of Harmony, is opened and threatens to suck in the planet unless the Doctor can close it with an atomic clock.

Based on an idea suggested in 1879, using atomic transitions to accurately measure time, the first atomic clock was built in the UK in 1955, and a substantial (in size and cost) commercial option was subsequently available. Though smaller atomic clocks were soon made, it wasn’t until 2004 that a chip-scale version was made.

Still, it reflects early concerns about the so-called Y2K bug, namely what might have happened if computers couldn’t get their metaphorical heads around the date switching from 1999 to 2000.

A man-made object made by manipulating atomic physics had the potential to save the day, but the actual threat here is advanced alien technology.

The everyday isn’t the only concern: a great fear is technology beyond our control – for instance, weapons of mass destruction used for political agendas. 2013’s Cold War was an examination of the 1980s climate of fear; as the Doctor says, “East and West standing on the brink of nuclear oblivion. Lots of itchy fingers on the button… Hair, shoulder pads, nukes: it’s the ’80s. Everything’s bigger”.

Indeed, if we look at the Fifth Doctor story, Warriors of the Deep (1984), writer Johnny Byrne could foresee similar tensions lasting into the year 2084. I guess we’ll see whether that’s true or not.

When Doctor Who did return to our screens, there was a new technological landscape to explore: computers being commonplace, the Internet, and cellphones!

2005’s aforementioned The Long Game flirted with the idea of body augmentation as journalists collated news using chips surgically implanted into their heads.

However, it wasn’t until the following year’s Rise of the Cybermen/ The Age of Steel that the production team fully explored technology integration. Reworking the notion of inter-connectivity working against us, an alternative genesis of the Cybermen showed how The Invasion‘s International Electromatics (acting as Cybus Industries) could have conquered Earth easier using Bluetooth.

The Doctor naturally subverts this, and the EarPod devices and downloads that enslaved humanity are turned against the Cybermen; making all technology compatible leaves the enemies essentially at the mercy of an emotional virus.

Similarly, the Sontarans turn our own technology and subsequent concerns about global warming against us in the form of ATMOS, a GPS navigation device that also threads throughout a car and reduces its carbon dioxide emissions to zero. The idea brings new meaning to the phrase, “This is your final destination!” ATMOS then releases alien gas that threatens to choke the planet, as a not-so-subtle (but nonetheless effective) warning about global warming; it’s no coincidence this two-parter is called The Sontaran Stratagem/The Poison Sky.

Commonplace technology has consequences. But that’s what Doctor Who does: turn the things we take for granted into everyday nightmares – and that’s not solely technology. Shop window mannequins, statues, and even the subway cannot be trusted.

It was only a matter of time before we were warned about Wi-Fi.

The Great Intelligence was created for The Abominable Snowmen (1967), a disembodied sentience capable of taking control of humans and robots; a much-loved classic monster, the Intelligence appeared only twice in the original 1963-1989 run of stories, but made a comeback in 2012’s The Snowmen. The following year, it returned in The Bells of St. John, harvesting minds through Wi-Fi.

Our long-term exposure to wireless signals meant the Intelligence could control its “cattle” better than ever before – “hacking” them and altering IQs, conscience, obedience, and paranoia – while occasionally trapping particular minds in the Internet permanently.

As head of the corporation rolling out this infected Internet signal, Miss Kizlet describes their objective as, “preserving living minds in permanent form in the data cloud. It’s like immortality, only fatal”. Whereas in The Web of Fear (1968), the creature had a physical web, the Intelligence had integrated itself into the online “Web”.

When Matt Smith’s Eleventh Doctor debuted, he used technology to save us after the Atraxi plan to incinerate Earth in order to destroy their escaped prisoner. In 2010’s The Eleventh Hour, he concocts a virus on a smartphone, resetting all counters to zero, thus alerting the Atraxi to the whereabouts of Prisoner Zero.

And that’s the thing about Doctor Who: it reflects the values and fears of nations, but the Doctor is always there to help – and often by using a foe’s technology against them. So, while Doctor Who has charted humanity’s fear of new technology over the past 50 years, the ultimate message is one of hope, salvation, and using technological advances to our advantage.

Which episodes do you think tech-savvy folk should watch? What new technology should Doctor Who exploit next? What new or future technology do you fear? Please let us know in the comments below!

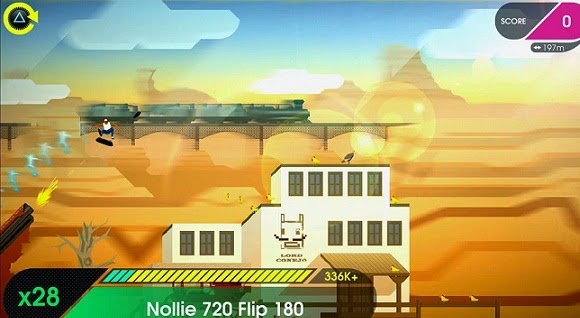

OlliOlli 2 (PSN) review

OlliOlli 2 (PSN) review Destiny Wanted Bounty Location Guide For Week (Aug 11 to Aug 17): Map Location & More

Destiny Wanted Bounty Location Guide For Week (Aug 11 to Aug 17): Map Location & More Dantes Inferno Guide

Dantes Inferno Guide Crysis 3 Achievements | Trophy Video Unlock Guide

Crysis 3 Achievements | Trophy Video Unlock Guide FF14: I Believe I Can Fly – How to Unlock Flying and Aether Current Locations

FF14: I Believe I Can Fly – How to Unlock Flying and Aether Current Locations