We often think of procrastination as an unnecessary hindrance to our everyday lives. But if it weren’t for procrastination, the world would be an entirely different place.

When journalist Don Marquis wrote that “procrastination is the art of keeping up with yesterday,” he blundered. In focusing on the idea that procrastination prevents us from advancing further than we were yesterday, he failed to see the colossal impact — both positive and negative — that procrastination can have on tomorrow.

Indeed, the origin of the term stems from the late 16th Century Latin, procrastinat which translates directly to “deferred until tomorrow.” If we look at it this way, it is not just the actions and decisions which are deferred until tomorrow, but so are the long-lasting, world-changing results that stem from procrastination.

We have a whole lot to both thank and blame these procrastinators for. From uncountable suffering, to the greatest works of fiction. From impressive technological feats, to the upending of industries. Despite the inevitable sprinkling of tardiness and indecision, the story of how procrastination changed the world is definitely one worth reading.

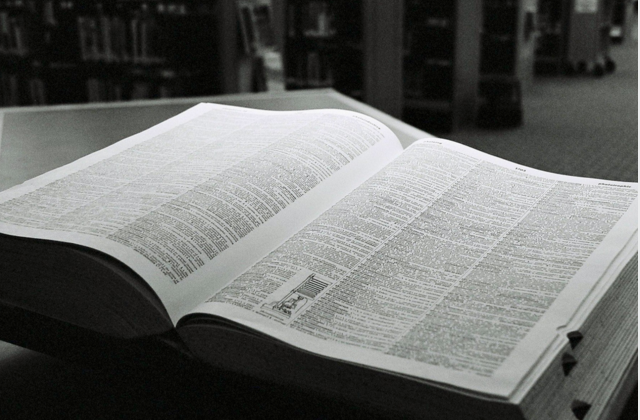

In 1755, Samuel Johnson eventually got around to publishing his enormous masterpiece; A Dictionary of The English Language. This was a work Johnson promised could be completed in three years. The final manuscript was turned in four years late, with the apt definition of “procrastination” simply reading Delay; dilatoriness.

Johnson was well known for being a chronic procrastinator. One of his greatest friends told that almost all of Johnson’s writing, including his much-loved essay on procrastination, was composed last minute. If it weren’t for Johnson’s dilatoriness, his work may well not have been so great, and his name erased from the annals of history.

How Johnson defined procrastination, however, leaves room for improvement. Procrastination researcher Timothy Pychyl added that “all procrastination is delay, but not all delay is procrastination.” The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) more fully defined the term as delaying, “often with the sense of deferring though indecision, when early action would have been preferable.”

It’s this more nuanced definition from the OED that I will mostly be using from here on out.

The first clickable banner ad was sold in 1993 to law firm Heller Ehrman White & McAuliffe. Following this sale, online advertising became a behemoth of an industry. By 2002, Google — launched only a few years before — introduced the first Pay-Per-Click (PPC) advertising model. It’s this model that completely changed the online landscape.

Online publishers could now better fund their work. But at the same time, the Web was awash with banner ads, pop-ups, and pop-unders. Load times were slowing. Websites were looking cluttered. Adverts were infuriating. Users were getting tired.

In the same year that Google introduced PPC to the world, Henrik Aasted Sørensen was trying to avoid revising for an upcoming university exam.

The Danish born Computer Science student, excited by the prospect of creating extensions for the new Phoenix browser (later to become Firefox), used coding as his procrastination tool.

The result? Adblock.

From the day Adblock launched, it was a runaway success. By originally hiding (and now blocking) adverts from the page, it made Internet browsing once again simple and uncluttered.

In 2015, almost 200 million people were using Adblock or similar software, costing publishers $22 billion over the year. Its growth continues, forcing an unwanted conversation between publishers on how to remain profitable.

Speaking to Business Insider, Sørensen says of the publishing industry:

“Funding journalism through advertising seems largely unsustainable to me. The pressure it puts on journalists to constantly create output and generate page views is a race to the bottom for journalistic quality.”

Yet, it’s largely on the back of the results of Sørensen’s procrastination that users are starting to demand a Web with less ads. But without decent ad revenue, online publishers will either close their doors, shift to more “clickbait” articles, or move over to new, largely untested business models.

This really is a tipping point for the online publishing industry, built largely on the success of a small piece of code written by Sørensen, the procrastinator.

There lingers an irony behind the billions of dollars Google is losing to Adblockers. After all, a sizeable chunk of Google’s ubiquity could owe its thanks to procrastination, too.

When Google went public in 2002, co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin said in their IPO letter:

“We encourage our employees, in addition to their regular projects, to spend 20% of their time working on what they think will most benefit Google. This empowers them to be more creative and innovative. Many of our significant advances have happened in this manner. For example, AdSense for content, [Gmail, Google Maps] and Google News were [all] prototyped in ‘20% time’.”

AdSense is an advertisement service from Google. In 2014, revenue from this (and related services) was over $14 billion.

Other services mentioned, including Gmail and Google Maps, contributed a healthy amount to Google’s remaining $52 billion in revenue (2014).

In effect, Google’s engineers were given free reign to experiment. They were allowed, and actively encouraged, to put off other workloads in the name of creativity and innovation. A pile of to-do items could be left untouched for 20% of the week, with no backlash.

Although this is a slight stretching of the original OED definition of procrastination, it’s still very close.

The resultant services that Google launched thanks to this initiative, helped shape the company into what it is today. These services built revenues that shaped many aspects of our lives; from how we navigate (Google Maps) to how we interact with the world (Android, and soon, Google Glass).

But it’s in the labs of Google X — Google’s secret workshop — that the company’s huge reserves of cash are being put to their most exciting uses. Driverless cars. Ingestible sensors. Space elevators. Wind turbines in the sky.

Without that 20% of time to focus on things other than day-to-day tasks, Google would probably still be “just” a search engine. The success of delaying their engineers’ work for 20% of the week has contributed to Google’s status as one of the major World Changers of the 21st Century.

These technological developments are just the tip of a very large iceberg of developments that procrastination can claim some credit for.

Unsurprisingly, the world of Literature, scattered with its dillydallying writers, is another example worth looking at. In Measure for Measure, Shakespeare poetically addressed the propensity for people to delay:

“Our doubts are traitors, and make us lose the good we oft might win by fearing to attempt.”

If Victor Hugo didn’t have his servant strip him naked and lock him in his study until an agreed hour, Les Misérables may never have seen the light of day. The humming of I Dreamed a Dream would never have passed a person’s lips.

And then we turn our attention back to that chronic procrastinator, Samuel Johnson, or as many called him, Dr. Johnson. The Doc has been, and still is, a towering influence in English Literature. He is the first literary critic that many Lit. students will become familiar with. It is from him that they learn how to fearlessly deconstruct a work. It is Johnson, who first showed the literary world that it needn’t be pompous to be good.

But the list goes on. Canada’s most celebrated writer Margaret Atwood spends the mornings filled with anxiety, before forcing herself to write at around 3pm. Herman Melville made his wife chain him to his desk as motivation to finish one of the greatest works of fiction ever written: Moby Dick. Marcus Aurelius, more a philosopher than a writer, said in his ever-popular Meditations (now spurring on a renaissance in stoicism):

“Think of all the years passed by in which you said to yourself I’ll do it tomorrow.”

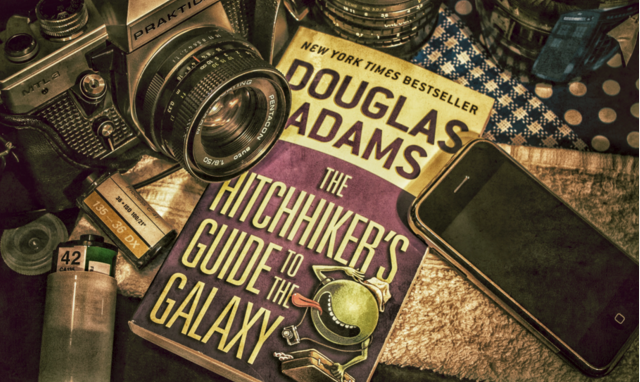

And then there’s Douglas Adams who joked of deadlines “I like the whooshing sound they make when they go by.” It’s Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy (1979) that MakeUseOf readers will likely be most familiar with. We’ve already written about how the franchise is influencing the way stories are told on different mediums. The original radio series spurred on other radio series, numerous novels, computer games, as well as a number of stage productions.

Guardian columnist Marcus O’Dair points at how Hitchhiker’s Guide helped to “pave the way for everything from Red Dwarf to Men in Black.” Stephen Fry explained that Adams’ masterpiece differed from all other science fiction in that “it was absolutely on a human scale.” Yet O’Dair goes on to show that:

“Large portions of the saga were conceived at the last possible minute, often under house arrest by whoever had the misfortune to be [Adams’] editor at any given point.”

However infuriating for his editors, it’s fair to say that Hitchhiker’s Guide would not have been what it is, nor what it’s become, if it weren’t for Adams’ penchant for procrastination.

We tend to think of religious leaders as men (and women) of decisive action. But this is far from the truth. After all, procrastination has lingered in Buddhism since its genesis. Ananda, the Buddha’s direct disciple, was supposed to ask the Buddha about which vows were minor ordinations, and which were major. After all, the Buddha was going to explain how the minor vows could be abolished. But Ananda kept delaying. The Buddha died. So now, 2500 years later, all vows are still taken by Buddhists, just to be safe.

“Procrastination is [moral] defilement” (Utthãna Sutta, v. 4P)

Much more recently, the Dalai Lama explained that as a young student, “only in the face of a difficult challenge or an urgent deadline would [he] study and work without laziness.”

Naturally, through Buddhist practice, he managed to overcome his idleness, going on to preach that:

“Since the illusion of permanence fosters procrastination, it is crucial to reflect repeatedly on the fact that death could come at any time.”

The Dalai Lama is now an inspiration around the world, especially in the West, where a new-found intrigue with secular spirituality is taking hold. It’s not too hard to imagine the spread of practices such as meditation, and the popularity of meditation apps (particularly HeadSpace) to be related to this fascination with the Dalai Lama and his own struggles with procrastination.

How Buddhist practices can help with procrastination is no secret. On a basic level, meditation can be used to train the mind to focus. To guide the mind into the zone. To harness attention more acutely. The Bell of Mindfulness is a Chrome extension that can help with this. By periodically reminding you to take a breath and refocus, you can catch yourself before you get sucked into a chain of procrastination. If you want something more invasive, try StayFocusd.

But deeper Buddhist practices, such as the incorporation of the eight-fold-path into your life, can help further. A main example being the ability to be fully immersed in whatever you choose to do by being able to let go of any other desires or distractions that crop up. If you don’t want to pursue Buddhism in itself, Urge Surfing is a technique that could be of use, also.

Johann Rall was a British Commander during the American War of Independence. It was during December of 1776 that Rall directly faced George Washington in the small but pivotal Battle of Trenton.

The night before that battle, Rall was enjoying an evening of chess and cards. Mid-game, he was handed a note from a local loyalist, alerting him to the nearby gathering of Washington’s forces. Too engrossed in his game, Rall placed the unread note in his pocket. It was only the next day, when Rall was leading his troops in retreat from the battle, that he was killed by a musket ball. The note was found unopened in his jacket pocket.

If Rall had in fact opened that letter, enabling for better battle preparations, the outcome could easily have been different. As it was, Washington took a huge number of prisoners, while suffering negligible losses. Washington’s resounding victory improved the flagging morale of the Continental Army, leading to many re-enlistments, ultimately contributing heavily to the overall outcome of the war.

Procrastination also rears its head in the American Civil War, with George B. McClellan famously putting more effort into preparing for war, than actually plucking up the courage to go into battle.

It is military leaders like these who we now — thanks to their procrastination — blame for the loss of battles and military advantages. Perhaps it would have been wise for men like these to read military leaders like Marcus Aurelius who also felt the urge to procrastinate. But Aurelius largely overcame this, allowing the Romans to once again dictate the political landscape of their time. What Aurelius said of procrastination would have been relevant in many of these examples:

“Ask yourself with regard to every present difficulty: ‘What is there in this that is unbearable and beyond endurance?‘”

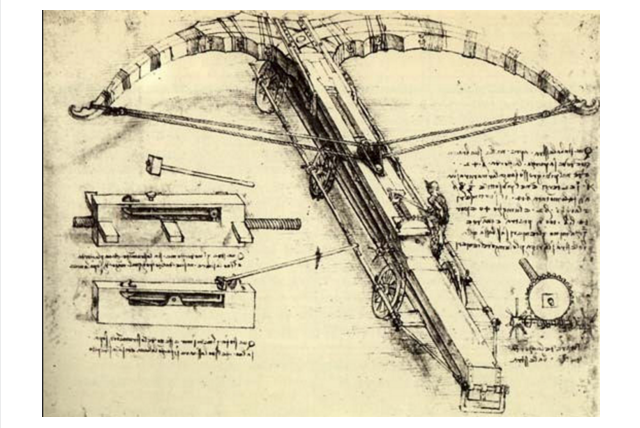

Lastly, we turn to that great Italian polymath, Leonardo da Vinci. His renown is great around the world, but his completed works are few. His incomplete works, on the other hand: they’re everywhere. Part completed architectural plans, sculptures, and paintings scatter da Vinci’s life.

The Renaissance man was famous among his peers for being unreliable. His customers were often left empty handed, needing to approach other artists to actually get their hands on a completed project. As just one example, da Vinci took 25 years to complete Virgin on the Rocks. Despite his dilatoriness, however, da Vinci’s impression on a huge number of industries outside of art remain incredible.

For it was da Vinci’s incessant curiosity to solve problems, and to learn new skills and subjects, that made it so hard for him to focus solely on completing his commissions. If it weren’t for his procrastination from these actual commissions, we wouldn’t be able to marvel over his 15th Century ideas for things like:

Most of da Vinci’s ideas were impossible to make reality until hundreds of years after their conception, but their inspiration on future generations of engineers and artists is beyond doubt. His work on human anatomy also spurred others on to more enthusiastically study the human body, leading to untold medical discoveries.

The idea that procrastination is something to be overcome is now largely the norm. The scientific studies surrounding procrastination tend to focus on why we procrastinate, and how we can stop. At MakeUseOf, we’ve written many times on how to beat procrastination, prevent Internet procrastination, stop procrastinating, and cut through procrastination.

But just as I recently aimed to show that productivity in and of itself is neither good nor bad, I hope to also have shown that procrastination in and of itself is neither good nor bad.

As we can see, the possible results of procrastination, though usually unintended (see AdBlock), can be profound and world-changing. Granted, we can use techniques such as structured procrastination or productive procrastination to make sure our delays are still productive (see da Vinci). But this isn’t required for procrastination to have some form of meaningful consequence. That being said, it’s probably still not something we should actively encourage.

However we look at it, procrastination has had an immense direct and indirect impact on the world. Some of those results have been positive, some negative, and for others (such as the ongoing conversation around online publishing), it’s just too soon to tell.

So before you go back to your procrastination, I leave you with one quote:

“This is the perplexing thing about procrastination: although it seems to involve avoiding unpleasant tasks, indulging in it generally doesn’t make people happy.” (James Surowiecki)

After reading this, do you think the world would have been a better or worse place, if it weren’t for procrastination? Is procrastination still something we should be seeking to obliterate?

Image Credits: Dictionary by Greeblie (Flickr), aaadorable! by Peter Petrus (FLickr), Eric Schmidt, Sergey Brin and Larry Page by Joi Ito (Flickr), always know where your towel is by Benjamin Balázs (Flickr), Les Miserable Weather by Garry Knight (Fickr), Meditation by Moyan Brenn (Flickr), The sun is shining brightly in the morning sky, through our American Flag. by Beverly & Pack (flickr). vinci_design_giant_crossbow_1482 by Art Gallery ErgsArt (Flickr), Procrastination A1 by Rachel Fisher (Flickr)

Destiny: The Taken King - How to Get The Touch of Malice Exotic Scout Rifle

Destiny: The Taken King - How to Get The Touch of Malice Exotic Scout Rifle Metal Gear Solid V The Phantom Pain: Africa Side OPs Walkthrough

Metal Gear Solid V The Phantom Pain: Africa Side OPs Walkthrough Top 10 Xbox 360 Games of 2013

Top 10 Xbox 360 Games of 2013 The Fallout 4 Rumor Dog

The Fallout 4 Rumor Dog Separation Anxiety - Diablo IIIs Dangerous Precedence of Always-Online-Singleplayer

Separation Anxiety - Diablo IIIs Dangerous Precedence of Always-Online-Singleplayer