Take a trip to Lusk and you will find a sign for a classic wood dining set for $250. Walk or fly around Luskwood and you will find what looks like an up-and-coming development with a few properties for sale. Land is also available in Ahern, Dore and Morris, and property values are surging.

An average day in suburbia? Not quite. This is a day inside Second Life, a virtual world created by San Francisco-based game developer Linden Lab.

Welcome to the virtual economy, where currencies such as the Linden dollar trade against the U.S. dollar, companies like Internet Gaming Entertainment (IGE) create markets for everything from magic shields to potions, and entrepreneurs sell notary services and the latest fashions. One of the most popular games, World of Warcraft, reached one million North American players in August, three months ahead of its first anniversary. The games are particularly hot in America and Asia. After World of Warcraft was released in China last June, 1.5 million paying customers signed up in a month.

Such ventures ?known as massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) ?have spawned economies that would rival those of a small country but fly largely under the radar of economists, government statisticians and people beyond the 12-to-35-year-old demographic. However, these economies are becoming increasingly important, says Wharton legal studies professor Dan Hunter, adding that they could redefine the concept of work, help test economic theories and contribute to the gross domestic product in the United States. 揑ncreasingly, these virtual economies are leading to real money trades,?notes Hunter, one of a handful of academics closely following this trend.

Another is Edward Castronova, a professor at Indiana University, who has written a series of papers examining the virtual economy which he estimates at somewhere between $200 million to $1 billion. In general, virtual economies are supported by assets collected during a game ?such as the power to slay a dragon ?that are then sold on the Internet for real dollars to other players looking for a competitive edge.

Steve Salyer, president of IGE, says the market for virtual asset trading could hit $1.5 billion in 2005 and $2.7 billion in 2006. Salyer's projections are a blend of internal data and research from outside sources such as DFC Intelligence and the Yankee Group. 揘obody can say for sure how big the market is,?adds Dmitri Williams, a speech communications professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 揑t's not like you can go on the street and poll people to find out.?In addition, he notes, many of the players who buy virtual goods are internationally based in locales such as China and Korea, making the dollars they spend hard to track.

While the size of the market is debatable, experts agree that virtual economies are expanding rapidly and warrant more attention. 揑t's really amazing that this hasn't gotten more attention,?says Kendall Whitehouse, senior director of information technology at Wharton. 揧ou can learn a lot from these worlds.?/p>

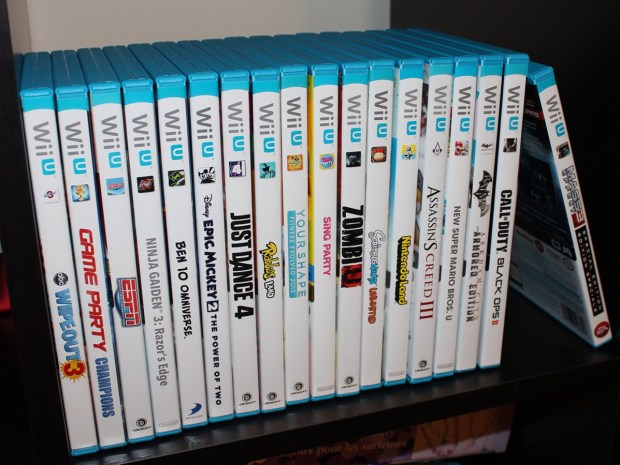

Sharing screenshots from Wii U in 5 easy steps

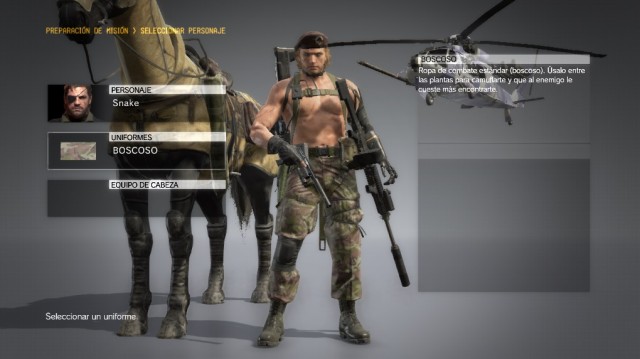

Sharing screenshots from Wii U in 5 easy steps MGS V: The Phantom Pain - Miller Head Replacer MOD

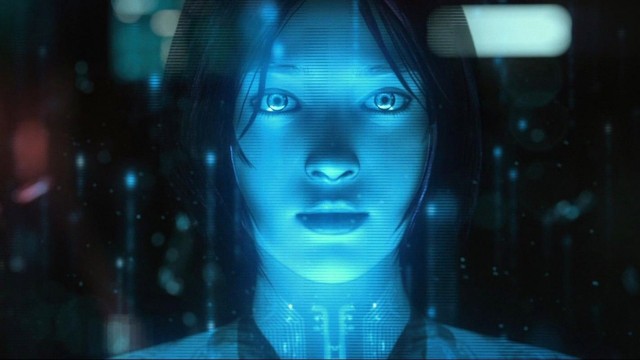

MGS V: The Phantom Pain - Miller Head Replacer MOD Mission 15 - Guardians: Halo 5 Guardians Walkthrough

Mission 15 - Guardians: Halo 5 Guardians Walkthrough Fallout 4: Kidnapped Trader walkthrough

Fallout 4: Kidnapped Trader walkthrough Halo: Reach Achievement Video Guide in HD

Halo: Reach Achievement Video Guide in HD