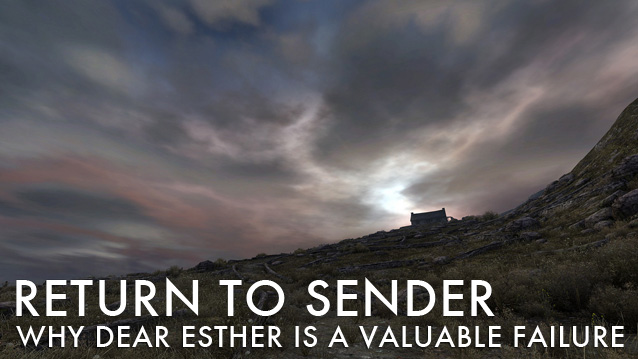

I wanted nothing more than to like Dear Esther, and at first, I really did. Each of the game's individual components made a remarkable first impression. The music set the mood perfectly, the narration flowed elegantly, and the craggy island that sprawled before me seemed a truly awe-inspiring display.

Without any real coherence, the game's eerie facade slowly crumbled until all I had left was ten minutes worth of plot spread thin over two hours of tiresome wandering.And yet, when all these beautiful things came together, they became somehow less than the sum of their parts. Soon, all sense of pacing vanished. Music seemed to start and stop in arbitrary fits. Scraps of story came slowly and unevenly. Even the island, once mysterious and brooding, gradually revealed itself as little more than an attractive corridor lined with invisible walls. Without any real coherence, the game's eerie facade slowly crumbled until all I had left was ten minutes worth of plot spread thin over two hours of tiresome wandering.

But even as I stepped away dissatisfied, an important question was picking at my brain: Why? Surely an experience that promising wouldn't collapse on me without good reason. While I can point to half a dozen niggling flaws, I think the problem is more systemic than that. Dear Esther seems to willfully ignore one important fact: without interactivity, games simply don't excel as a narrative medium.

That may sound like a hard pill to swallow, but think about it for a moment. Would you honestly say that watching someone silently play through the entirety of, say, Half-Life 2 would be more enjoyable than watching a well-crafted film adaptation of the same story? Of course not. Games really only have a leg up over other narrative mediums when they actively engage their core strength, interactivity. Now, that obviously includes branching storylines, but it goes far deeper than that.

All the interactive segments of a game, whether solving puzzles, slaying dragons, or shooting terrorists in their freedom-hating faces, are more than just distractions or filler designed to string together plot points. They throw us into a sandbox, teach us the rules, and tell us to play. And play we do. We imagine, we improvise, we choose, we create. Piece by piece, we write our own stories to fill the gaps. In the process, we both complete the narrative and become personally invested in it. It's for this very reason that games without any narrative at all can still be so compelling.

But Dear Esther clearly has no interest in engaging the medium on either of these fronts. Yes, the narration might be ordered or embellished differently every time you play, but that's merely the illusion of dynamism. The major beats will never change. The final outcome remains inevitable. If anything, this approach is almost more self-defeating, as it means that the bulk of the storytelling mechanics you encounter must be carefully designed to be expendable and repetitious, and that's certainly borne out in practice. The narration and set dressing hint at the Dear Esther's central secret so often with such little grace that you can't help but imagine the game is winking at you. "Did you get it yet? What about now? I'm going to tell you five more times, just to make sure." A good story, no matter how static, demands something of its audience, but Dear Esther seems so intent on spoonfeeding the player that it whisks away almost all opportunity for reasoning or interpretation.

The little there is that might be termed gameplay is similarly devoid of meaningful interaction. Dear Esther really only allows you to walk, look around, and zoom in slightly on whatever it is you're looking at. Everything else, from jumping to crouching to activating a flashlight, is handled automatically by the game. To a lesser extent, you're also free to explore the island, probing into some optional nooks and crannies, but all you'll really gain is a few of the game's two dozen or so props scattered about and, if you're lucky, a new piece of narration. Even if you make a concerted effort to take every detour, you won't have far to go before you're forced to amble back onto the main path.

Dear Esther seems to willfully ignore one important fact: without interactivity, games simply don't excel as a narrative medium.Then there's the ending, which is unquestionably Dear Esther's most flagrant offense. Just as the plot finally presents an opportunity to take meaningful action, control is wrested away from the player. What should have been a poignant, deliberate decision is instead reduced to a cheap, emotionally disconnected cutscene. In a way, it's the most glaring symptom of Dear Esther's core failing. The game places no faith in the your ability to become an active participant, and so it tears away all but the basest of freedoms. For everything that atmospheric setting does to immerse you in the experience, there's half a dozen needless restrictions to draw you back out. As a result, there's simply nothing about Dear Esther that demands it be a game rather than, say, an elaborate theme park ride. It's an art game with no game. It's interactive fiction with no interactivity.

Still, it's difficult for me to truly condemn what has been accomplished here. If nothing else, Dear Esther is a bold experiment in the limitations of its medium, and a failed experiment is just as valuable to our collective knowledge as a successful one. Disappointing though the outcome may be, Dear Esther should be commended for asking some uncommonly pointed questions: What can a game be? More importantly, what should a game be? In truth, I suppose all games engage those concepts on some subliminal level, but Dear Esther does so with an almost scientific rigor, stripping away variables until there's nothing left but a falsifiable formula. Does X plus Y plus Z equal game?

For me, at least, the answer is a resounding no. Dear Esther is not a successful use of the medium, nor is it a particularly worthwhile experience, but that doesn't mean it's not an admirable effort. For all its faults, Dear Esther is the sort of game we should all want to see more of: innovative, thoughtful, and wholly unafraid to question everything we take for granted.

19 Brilliant Gift Ideas for Music Lovers

19 Brilliant Gift Ideas for Music Lovers Best 5 Weapons in Xenoblade Chronicles X

Best 5 Weapons in Xenoblade Chronicles X Pokemon Platinum Guide

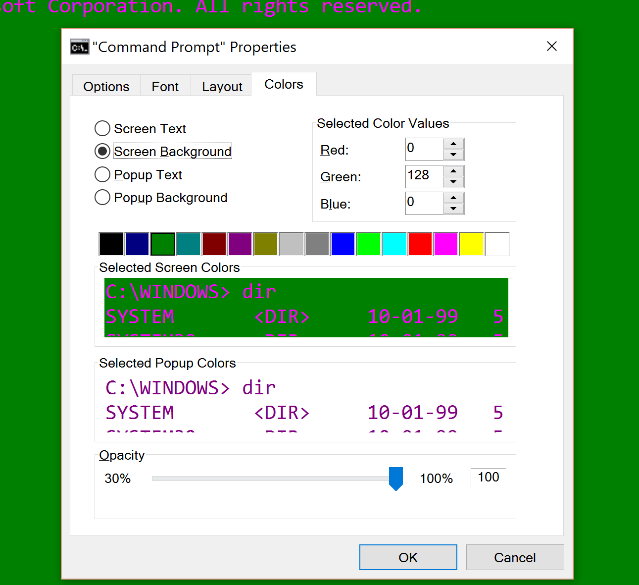

Pokemon Platinum Guide How to Change the Command Prompt Colors in Windows

How to Change the Command Prompt Colors in Windows 7 Twitch Streamers To Watch If eSports Aren't Your Thing

7 Twitch Streamers To Watch If eSports Aren't Your Thing