To begin this article on an agreeable note, I am going to go ahead and assume that both you, the reader, and I are geeks. When I say this, I mean that we enjoy ‘geeky’ pastimes: videogames, comic books, pen and paper roleplaying,and any combination of the above or otherwise unlisted. What I don’t mean to say is that we’re inherently socially inept, that we can’t start a conversation with the opposite sex because we’re frightened, or that social situations leave us frozen, paranoid, sweating in fear or worse, liable to make references to people who simply wouldn’t get them. I say this because geeks are not, by definition, ‘losers’. I say this because such an idea has pervaded popular culture for a while now. I say this because we don’t live in the world of The Breakfast Club – it’s okay to be a geek.

The problem is that it’s only really okay to be a geek from an outside perspective. It has become socially acceptable to mention that you play videogames or read comic books outside of a group of enthusiasts of that subject, but for some who have been identifying as geeks for years, even decades, this is beginning to defeat the purpose of the culture in its entirety.

Geek culture has always existed as a comfort zone for those who do not want to throw in their lot with the rest of the crowd; those who can only stand so much talk about gym routines, so many drinking games, so much sports coverage. It allowed its participants to, as Patton Oswalt put it, construct ‘otaku-esque thought palaces’ where they could revel in the intricacies of the most obscure facets of the arts, free from the judgment of those who didn’t understand. When geek culture first came about, these palaces were secretive and personal; one’s geekdom was one’s quirk. It individualised people, and therein lies the danger posed to geek culture by its increasing popularisation.

There’s no clear-cut answer on how or when it started, but some time or another, those who had spent all of those years building up their own exclusive part of the social structure woke up to find that its exclusivity was gone, and that presented the culture with a big problem.

The problem was that the paradigm shift brought about by the popularisation of geek artefacts made the culture obsolete. What was once the private reserve of the geek was now mainstream. It was like returning home after work to find a group of strangers in your front room watching TV as if nothing about the situation was strange or out of place.

And so, there was counter-action. Most of it came it the form of lashing out, labelling, and the exposing of some rather ugly sides of the human character. People were branded “fakes” and derided. Geek culture sought to hide away again, retreat from the light and withdraw into itself. This counter-action came to a head in a recent Forbes piece by Tara Brown in which she calls out “fake geek girls”, defined as girls who have a half-hearted interest in traditionally geeky pastimes, advertising this in order to gain attention. It’s a prime example of the way in which geek culture has morphed from a collective of like-minded people into a kind of proving ground; each person out to justify their claim to the “geek” moniker with a litany of credentials: PCs built, Dungeons & Dragons campaigns run, years spent buying issues of Batman, each item in the litany representing the culmination of years of work and dedication, each litany representing the strengthening of an elitist frame of mind that seeks to bar entry to those unworthy.

However, this method of preservation is ill-founded and is doing far more harm than good.

Geek culture faces a crisis of identity, slowly becoming worthless as it is diluted by volume.Geek culture faces a crisis of identity, slowly becoming worthless as it is diluted by volume. But the solution to the problem is not to hack away at the new growth like it is a tumour that must be excised, nor is it, as Oswalt suggests, to make the culture implode so that we may start it anew. Instead, we need to repurpose the culture. We need to take advantage of the movement of the tide of mainstream thinking. We need to get beyond The Breakfast Club and we need to do it now.

The real solution is simple. Instead of trying to maintain a minority status and promoting elitist views of what it means to be a geek, we must instead welcome these newcomers into our folds. We have to embrace these new recruits and show them how they can become stronger otakus, more knowledgeable in the field that they have displayed an interest in. As Susana Polo writes:

“The proper response to someone who says they like comics and has only read Scott Pilgrim is to recommend some more comics for them (...) The proper response to someone who appears to want to be a part of your community is to welcome them in.”

In the best case scenario, we will help create new geeks, and our subculture will experience a regeneration as more and more people come to appreciate the intricacies of Shadow of the Colossus, the themes and messages of Braid or the complexities of the DC Multiverse. In the worst case scenario, these newcomers to our culture will find out that maybe geekdom is not for them, the swell in interest will fade, things will return to the way they were, and in years to come we will look back on it as a fad, a phase in the history of mainstream culture.

What we must not do is let vitriol rule the discourse. We must not create ‘outsiders’ as a result of our own inane assertions on what it means to be a geek because that is what will rot us from the inside more than anything else.

Therefore, my comrades, I beseech you to be that mentor that somebody new to our culture really needs. The next time someone claims to be a total gamer because they once knew a guy who played Gears of War, make it your duty to broaden their horizons. You have nothing to lose, but the geek collective definitely has something to gain.

Can You Play Games On A Windows 8 Tablet?

Can You Play Games On A Windows 8 Tablet? Why I Bought My iPhone Straight from Apple (And You Should Too)

Why I Bought My iPhone Straight from Apple (And You Should Too) How to use Remote Play or second screen with PS4

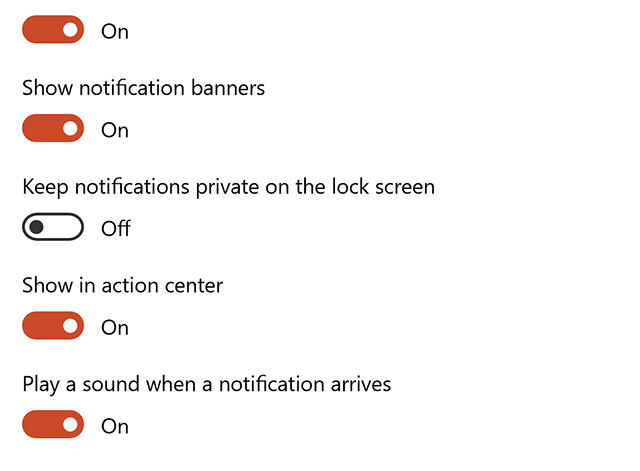

How to use Remote Play or second screen with PS4 How to Turn Off Notifications for Specific Apps in Windows 10

How to Turn Off Notifications for Specific Apps in Windows 10 Oceanhorn Walkthrough Cheats Video Guide

Oceanhorn Walkthrough Cheats Video Guide