When we’re told that a game contains violence, what do we think that means? Do we imagine body parts and blood, kicks, punches, bullets and bombs? Do we immediately imagine depictions of gore and mutilation? Are we mowing down waves of enemies with an M-16? That’s pretty much violence, right?

One of the more curious false continuums lobbed forth in defence against contemporary accusations of sexism and rape culture within videogame culture (including discourse over the contentious Hitman trailer and Tentacle Bento, the now-infamous card game rather belatedly cancelled by Kickstarter), was that, because we take heinous violence of other types for granted in videogames, we should therefore not be so hard on the apparently-targeted issue of sexual violence in games. There are two fundamental problems with this particular line of rhetoric: the first is that it assumes that different forms of violence are indistinct and should therefore be thought of as being under the same terminological umbrella; the second is that it assumes that because we take certain kinds of violence for granted, not only is this something we should continue to do, but that we should extend it to the horrendous and violent act of rape.

Now, I understand the reasoning to an extent. It’s a double-standard, apparently that we let other forms of violence go, but huff and puff all day about, for instance, a cute, “cheeky” game about sexually assaulting teenagers in the form of an extraterrestrial cephalopod.

And this is the only extent of that argument which matters, because you know something? We shouldn’t be taking other forms of violence for granted when they bleed into games from existing social and cultural issues, and the prevalence and attitude towards rape is definitely one of those things.

Before you turn purple and start smoking from the ears, let’s just get one thing straight: I play plenty of violent games myself. I am no Jack Thompson. I certainly don’t think games are “murder simulators.” I have no problem feeling a giddy thrill from God Hand, House of the Dead or Street Fighter, and I likely never will. I certainly don’t think games have some substantial power to magically make people more violent. But the essential line between the enjoyment of fantasy violence and violence and apologia which derives from the prevalence of cultural and social ideologies and attitudes is not one we should be trying to blur. That is erasure; that is obfuscation, and it does us no good.

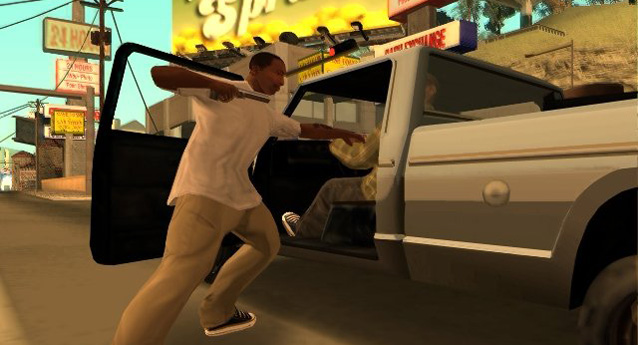

Take, for instance, ghetto warfare in San Andreas, and its intrinsic relationship to American race issues as developed by Rockstar North, in Scotland. Fundamental to understanding why violent depiction is important is in realizing that it has little to do with violence itself, and more with how the violence is contextualized and to which ideas it is associated. Classism, gang war, drug use and racial tension are rolled up into a great big ball, according to Aaron Myles, and the question one must ask when playing a game like this is in asking whether or not the type of violence and abjection being portrayed isn’t being glorified or normalized. We must ask if this is an honest, thoughtful satire of these problems in order to bring some insight them, or whether or not it’s exploiting them for the purpose of entertaining a specific demographic—one which may have nothing to do with the ones depicted in the game.

What about military and foreign policy as presented in games? How does the success rate of torture in—well a number of games, actually—sit with you? Does it convey, perhaps, the idea that government sanctioned torture is an appropriate and effective thing? Does Punisher allow you to make exceptions or rationalize torture as long as it’s being done by the good guys? Even if we’re ok with violence itself in games, do we not ask whether or not these depictions of real-world problems are ok? Do we question how they’re being transmitted to us and what the attitude is surrounding them? I think we ought to, and not just for games. We should be questioning violent depiction in all media and what it says about our culture and what’s being inculcated in us as a result. We can do this for art from past eras with a fairly objective head. There’s no reason we shouldn’t be equally conscientious about what we’re consuming now.

So let’s return to sexual violence in games. Take Tentacle Bento: What is it about how rape is contextualized in this game which makes it so problematic? Why is it different from the harrowing, infamous Silent Hill 2 scene? The distinction here is easy to draw: one is meant to be horrifying. The other is not. Tentacle Bento is supposed to be “cheeky” and “fun,” with the fact of its being “horrible” as kind of an insincere, trivialized afterthought. Does Tentacle Bento necessarily promote rape in the real world? Maybe not. But something I hear repeatedly in its defence is that the game is based around a fantastical trope, and therefore does not represent anything realistic.

I want us to think about the representation of types of violence in games as potentially being reflections of things which happen in the real world, framed by an attitude with which we approach the concept and its subjects.The problem with this is that arguing for the pure realism of something as making it uniquely capable of conveying ideas is patently false. Art does not need to be realistic to spread real ideas. There are clearly elements of San Andreas or Punisher which are already far from realistic, while being aesthetically verisimilar to realism. Tentacle Bento does not need to represent human-on-human sexual assault to convey the attitude of rape being flippant, fun and normalized. It even went so far as to offer players the chance to put a female loved on in the game—with or without—their consent, which is a blurring of the real and the fake if I’ve ever seen one. The problem with Tentacle Bento has nothing to do with tentacles. In some ways, the problem isn’t even in representing rape as a concept. The real issue is in how rape is being represented: how it is so fundamental a mechanic to playing that it does not shock in quite the way it probably should. Rape is so profoundly and intrinsically a part of player success in this game that its very real, very distinctive complexities and trauma are totally undermined.

I’ll be honest: I don’t want this to devolve into a discussion over whether or not the game should or should not have been cancelled or a derailment into censorship discourse. What I want is to use this experience as an opportunity for us to talk about the ideas that games and other media are capable of putting in our heads, and to which extent we take this type of enculturation for granted. I want us to think about the representation of types of violence in games as potentially being reflections of things which happen in the real world, framed by an attitude with which we approach the concept and its subjects. I want us to wonder whether or not those reflections and frameworks are problematic or incomplete, considering the realities of those problems. I want us to think about how we can improve representation, heighten our insight toward these issues, and extend compassion and empathy toward victims of different kinds of violence rather than demean, ignore and even spite them for the purposes of entertaining ourselves.

The way to rectify whatever double-standard exists is not in pretending that all violence should be thought of as alike. This is a profoundly lazy, entitled and oblivious way to approach these issues. Sure, videogames are not violence simulators—this is a ridiculous strawman—but no less are they “simple entertainment” incapable of affecting the way we think about the world around us. So we must address them with a respect for nuance. Games, like all media, are capable of influencing our attitudes toward real-world social ills, how we process them and how seriously we take them. This is a far cry from videogames actually making us do anything, but is still hugely important to how we internalize and think about our culture. We must be vigilant and reflective about the ideas presented in games, and we must freely and conscientiously express those concerns. If we fail to have that dialogue, we fail as a culture.

5 Tips To Improve Your Prison in Prison Architect

5 Tips To Improve Your Prison in Prison Architect Sequence 7 - Motion to Impeach: Kill the Earl of Cardigan - Assassin's Creed: Syndicate Walkthrough

Sequence 7 - Motion to Impeach: Kill the Earl of Cardigan - Assassin's Creed: Syndicate Walkthrough Pokemon ORAS Tip: Get a 100% encounter rate for Feebas at this location

Pokemon ORAS Tip: Get a 100% encounter rate for Feebas at this location 5 Ways Gamers Can Save Game Progress To The Cloud

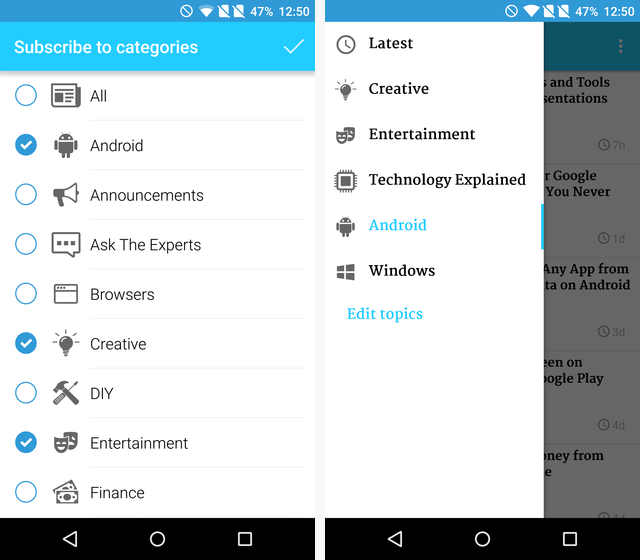

5 Ways Gamers Can Save Game Progress To The Cloud Download the New MakeUseOf App for Android

Download the New MakeUseOf App for Android