The worst thing you can do in Ziggurat is miss.

As the game progresses and the alien robots approach in increasingly large numbers, missing a crucial shot can mean death. That one missed shot, that orb of green energy flying off the screen under and over the swarms, can mean, simply, that you will be overrun. You no longer have the second it will take to charge another shot and suppress both sides of the ziggurat before one of them takes you out. Think about the traumatic consequences of dropping a block into the wrong column several stages into a game of Tetris; that’s how bad it feels to misfire in Ziggurat.

But there is more to missing in Ziggurat than simply firing on the wrong trajectory. Ziggurat is a careful balance of excess and temptation, of not biting off more than you chew. This is most clear with the laser rifle that is constantly tempting you to charge it to full power, but which really doesn’t need to be. Often, a less powerful charge is all you need to clear a side of the ziggurat, but we have been conditioned by decades of videogames telling us that bigger is better and we just can’t resist the urge to fire a full-powered shot.

Ziggurat deliberately exploits this. Most tellingly, there is the fact that the most powerful charge is available a moment before full charge—charge for too long and the energy ball shrivel back down to a mid-size thing. In other words, a fully charged shot is not a fully charged shot.

But where Ziggurat most harshly punishes the player for trying to be excessive is when you try to fire a fully charged shot down either side of the ziggurat. Keeping the slopes of the mountain clear are crucial to humanity’s ongoing survival. Yellow enemies, instead of jumping up into the air, simply walk up the sides of the mountain, trying to catch you unawares. Red ones, meanwhile, stand stationary right at the bottom of the slopes, in either corner of the screen, before they leap right at you. Taking them out before they jump can be a huge time saver.

And it should be easy to take them out—just lob a quick, tiny shot down there. But so often—so often—I try to fire a fully charged shot down the slopes of the ziggurat, a shot far larger than is needed. Such a shot, without fail, will hit the ziggurat itself, and the excessive power behind it will ricochet it up into the air like a smooth stone off a lake, flying harmlessly over all the yellow and red robots that a far weaker shot could have demolished in half the time.

It is one of the worst feelings I have ever felt in a videogame, watching that wasted ball of energy and time hit the rock and bounce away into nothing. Every time I do it I know that the game has tempted me into being greedy, into wanting to use a larger shot than was necessary. Every time I do it, I know I’ve taken the bait and fallen for the same joke yet again. I could have dribbled the tiniest shots down the side of the ziggurat and wiped them all out but, no, I wanted the explosion. And now the sky is full of white robots again and I won’t have a chance to take out the red one until it is right in front of me. I had a chance to get on the front foot, but my greed put me on the backfoot. All because of one stupid missed shot.

It’s what makes Ziggurat so mechanically engaging. Much like Dark Souls, you have to teach yourself discipline. You have to teach yourself not to be impatient, not to overreach. Even after you have mastered Ziggurat, there is still plenty to learn. You still have to master yourself.

Dragon Age II: A Revolutionary RPG in the Making

Dragon Age II: A Revolutionary RPG in the Making How to Fix NBA 2K16 Crashes & Errors, NBA 2K16 My Team Black Screen and More

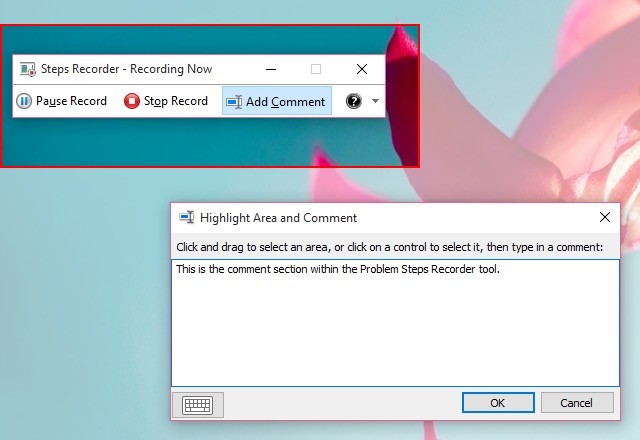

How to Fix NBA 2K16 Crashes & Errors, NBA 2K16 My Team Black Screen and More Try This Built-In Windows Tool to Record System Issues

Try This Built-In Windows Tool to Record System Issues Civilization V: DLC Done Right

Civilization V: DLC Done Right Dark Souls 2 Weapons and Shields Guide - Daggers and Fist Weapons

Dark Souls 2 Weapons and Shields Guide - Daggers and Fist Weapons