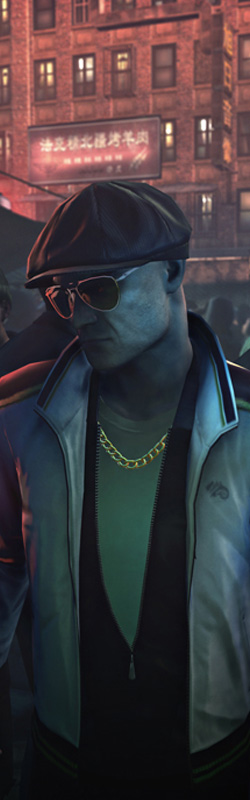

What went wrong with Hitman: Absolution? Too simple, too linear and too confined is the consensus: IO Interactive abandoned the traditions of the Hitman series and it cost them. That’s not to mention the homophobia, and the misogyny of that infamous ‘leather nuns’ trailer. It’s not right, many have cried; Hitman is supposed to be classy! But for all the ways Absolution diverges from its forbears, sexual politics is not among them. This is a reading of Hitman: Contracts and Hitman: Blood Money as socially conservative treatises on human sin and moral frailty—of which the Saints are just the logical conclusion.

Hitman is rightly rightly famous for their larger-than-life villains. Once the series hit its stride with Contracts, no other game could match its rogues’ gallery of colourful bastards, and few could approach the sense of heightened reality in its levels. By Blood Money, the apex of the series, playing the game was like stepping into the fevered imagination of its targets; think Psychonauts with razor wire.

Hitman is rightly rightly famous for their larger-than-life villains. Once the series hit its stride with Contracts, no other game could match its rogues’ gallery of colourful bastards, and few could approach the sense of heightened reality in its levels. By Blood Money, the apex of the series, playing the game was like stepping into the fevered imagination of its targets; think Psychonauts with razor wire.

Far from erasing individuals, then, as Cameron Kunzelman has suggested, Hitman is full of character studies. Where most games give you endless tides of faceless goons, each target here has his own quirks and foibles. Some are quietly touching, like the way drug lord Fernando Delgado (‘A Fine Vintage’) retreats periodically to his room to play the cello. Others, like the secret passage and two-way mirror installed by Lord Beldingford to spy on his maids while they shower (‘The Beldingford Manor’), are simply grotesque. Most are funny: if you impersonate a therapist in ‘Flatline’ you can sit down with your marks for a spot of psychoanalysis (the very science of individuality). Either way, to solve a mission involves becoming intimate with the habits and eccentricities of your serial victim.

These touches are not just window-dressing. Delgado’s jam session can be interrupted, and Beldingford’s secret passage allows covert access to his bedroom. By making each quirk a manipulable game element, Hitman maps personality onto the clockwork of each level, so that vices become vulnerabilities and sins are security breaches. In tragedy, the hero’s downfall is the logical consequence of his personality. Here, if you play well, that is literally true.

Take Campbell Sturrock, the murderous meat balloon who covers a bed like a medieval personification of Gluttony (‘The Meat King’s Party’). Regular deliveries of whole fried chicken provide an easy way to smuggle a weapon into his chamber. Playboy Chad Bingham’s weakness is the same eager penis that made him a liability to his Senator father; slip him an aphrodisiac, wait until he’s done fucking, and choke him as he enjoys a post-coital smoke (‘You Better Watch Out…’). Beldingford’s voyeurism renders his own room insecure, and while Fernando Delgado is best killed while practicing his Bach, his son, Manuel, has the unfortunate but convenient habit of retreating to a basement to sample his own merchandise. These are just examples plucked from a cast of eaters, drinkers and fuckers whose appetites make easy vectors for a poisonous death.

‘Flatline’, a mission from Blood Money literally set in a rehab clinic, is easily the most striking. The situation is explicitly psychological: this is a place where people are imprisoned to protect themselves from their own destructive behaviour. The militarised boundaries and guarded checkpoints which make up the game’s bread and butter exist here as much to keep the inmates sober as to keep intruders out. But the system can’t protect your targets if they insist on subverting it. The mobsters seal their own fates with regular visits to secret booze caches, which, through careful observation, you can find and poison. It’s a clever setup because we already think about addiction in this way—both a crime and a sickness, a moral trespass and a fatal weakness. We are exploiting these men, but they also allow it to happen.

‘Flatline’, a mission from Blood Money literally set in a rehab clinic, is easily the most striking. The situation is explicitly psychological: this is a place where people are imprisoned to protect themselves from their own destructive behaviour. The militarised boundaries and guarded checkpoints which make up the game’s bread and butter exist here as much to keep the inmates sober as to keep intruders out. But the system can’t protect your targets if they insist on subverting it. The mobsters seal their own fates with regular visits to secret booze caches, which, through careful observation, you can find and poison. It’s a clever setup because we already think about addiction in this way—both a crime and a sickness, a moral trespass and a fatal weakness. We are exploiting these men, but they also allow it to happen.

Others targets are made most vulnerable by their relationships. The two assassins in ‘The Murder of Crows’ betray their positions by flirting with each other over the radio (and incentivise their own destruction with godawful puns). Vaana Ketlyn, in the theologically-themed ‘A Dance With the Devil’, will invite you into a convenient killing space if you first dispatch and disguise yourself as her masked lover. Most telling, however, are the stars of the glorious ‘Curtains Down’ mission. A briefing implies—without saying outright—that your targets are lovers, in language which treats their homosexuality as a scandalous secret (“almost inseparable”; “a sordid fascination bordering on obsession”). In case you miss that, a sneering French cloakroom clerk provides some prurient wink-nudge commentary on the liaison. This knowledge can be exploited: if one target dies on stage, the other, normally surrounded by bodyguards, will run out into the open.

There is something purgatorial in the way these people circle and circle their private drains (what Kunzelman calls “serial repetitions"). They’re stuck in a rut, refusing to abandon the patterns and flaws which constitute their character; in the phase space of repeated play their comings and goings have a distinct shape which you can navigate.

But if you think this is all starting to sound a little regressive, then yeah, no shit. In Hitman’s world, everyone is alternately vain, venal, crooked, foul, lecherous, vulgar, vile, wanton, gross, obscene, pathetic, or perverted, and your job is to visit upon them a vengeance for their moral disgrace. I this loaded language advisedly: although Hitman’s Catholic overtones are so arch and silly that it’s tempting not to take them seriously, its model of sin and vice is properly old-school.

Nowhere is this more clear than in its treatment of sex. Chad Bingham, Vaana Ketlyn and Lord Beldingford are joined by Skip Muldoon, the steamboat captain with a weakness for sweet things and subordinates dressed as sailor boys (‘Death on the Mississippi’), and Vinnie Sinistra, the suburban gangster who entrusts the crucial microfilm to a drunken, randy wife who’ll come upstairs with you if you dress as a pool boy (‘A New Life’). Aesthetically, the portrayal of these characters—as a rampant queen and a disloyal bimbo respectively—is of a piece with the fat-shaming caricature of the Meat King or the homophobic conflation of the operagoers’ sexuality with their participation in a pedophile ring. But moreover, on the level of play, this trope of the target lured into vulnerability by the promise of sex crops up again and again; in the world of Hitman, sexual privacy is fatal, and female sexuality in particular is frequently monstrous.

Nowhere is this more clear than in its treatment of sex. Chad Bingham, Vaana Ketlyn and Lord Beldingford are joined by Skip Muldoon, the steamboat captain with a weakness for sweet things and subordinates dressed as sailor boys (‘Death on the Mississippi’), and Vinnie Sinistra, the suburban gangster who entrusts the crucial microfilm to a drunken, randy wife who’ll come upstairs with you if you dress as a pool boy (‘A New Life’). Aesthetically, the portrayal of these characters—as a rampant queen and a disloyal bimbo respectively—is of a piece with the fat-shaming caricature of the Meat King or the homophobic conflation of the operagoers’ sexuality with their participation in a pedophile ring. But moreover, on the level of play, this trope of the target lured into vulnerability by the promise of sex crops up again and again; in the world of Hitman, sexual privacy is fatal, and female sexuality in particular is frequently monstrous.

Just look at the points in Blood Money where 47 himself is tested for flaws. In ‘A Dance With the Devil’, two assassins are sent to intercept him. One, the man, is brash enough to reveal himself in conversation and challenge him to a duel in a locked backroom. But other, a woman, will invite 47 coyly off-set for hanky-panky and then stab him to death in an outlandishly sexualised cut-scene. Another scantily-clad hitwoman appears in ‘You Better Watch Out…’, trying to tempt you into a private room. “Men are so easy,” she tuts if she succeeds. “Shame to waste such a nice hunk of meat.” These aren’t just killers who use sex, but sexual killers, women driven by murderous libido. Blood Money inherits from the Christian tradition a fundamental misogyny which says women are either scheming temptresses or obliviously wanton; in either case they are to be punished.

In a canonical playthrough, however, 47 will never be tempted. Unlike his enemies, he has no personality and therefore no vices; designed to be anonymous, distinguishable only by his barcode, he is a blank human being (as long as you pretend that ‘white’ and ‘male’ are blank attributes). Moreover, his violence is simply violence, bought and paid for, existing only in the sexless realm of business. Their violence is obscene, sexual; like the shrieking assassin who cartwheels around like a gymnast and orgasms when she kills, they enjoy their victims. So a killer he may be, says the game, but he knows what he does, confesses his sins, and commits them without self-deception or corruption or abandon. He is not like his targets. Of all hell’s denizens, he, at least, is pure.

Of course we can see through this nonsense. Nothing could be more perverse than to plumb the depths of humanity’s depravity while fetishizing one’s own exemption from it. On the contrary, this sexless saviour needs the sinful world, needs the perverts in order to license his sanctimonious and violent chastity; the erotic frisson of vice and virtue cannot cannot be his without something to reject or someone to rebuff or a wickedness to grimly avenge. We can imagine him getting off on his own purity, big hairless penis that he is, furiously masturbating under his heavy suit as he fantasizes about the futile touch of a whore’s supple hand on that hard, uncaring shoulder. I work alone, he will say, tweaking his nipple through his spotless shirt.

Of course we can see through this nonsense. Nothing could be more perverse than to plumb the depths of humanity’s depravity while fetishizing one’s own exemption from it. On the contrary, this sexless saviour needs the sinful world, needs the perverts in order to license his sanctimonious and violent chastity; the erotic frisson of vice and virtue cannot cannot be his without something to reject or someone to rebuff or a wickedness to grimly avenge. We can imagine him getting off on his own purity, big hairless penis that he is, furiously masturbating under his heavy suit as he fantasizes about the futile touch of a whore’s supple hand on that hard, uncaring shoulder. I work alone, he will say, tweaking his nipple through his spotless shirt.

Given all this, what are we to make of Hitman’s overt religiosity? Its angels and devils, its fluttering wings? Mere lampshade-hanging; an aesthetic double bluff which prevents us from assuming that the game’s reactionary moral universe is sincere. The knowing deployment of kitsch is a signature of the postmodern and indicates what tremendous fun the game is having with its pseudo-Catholic schtick—but poses no challenge to the underlying ideas. These games gleefully, shlockily, self-consciously (but ultimately uncritically recycle a medieval morality which includes lust and even homosexuality in the category of sin.

So Absolution’s leather nuns are entirely consistent with the previous games. They’ve always used religion, perversion and sexuality to push players’ buttons. As Keza MacDonald noted way back when the Saints trailer first surfaced:

The typical innocence/sin imagery of a naughty nun is warped here to extreme proportions, providing a kind of obscene justification for the violence; as if, because they look like they do, they probably deserve to get taught a lesson, the slutty whores.

This is precisely the regressive attitude Hitman takes to all its targets. They use religious ideas of perversion and sin as shortcuts to them up with vices which invite and enable their own punishment and use religious ideas of perversion to

What filthy people, the player is supposed to muse—what a vile animal is man—and how pernicious woman! Then coldly deploy poetic ‘justice’. We shouldn’t be surprised that when women enter this classic set-up, things get unpleasant in a very familiar way.

All this might actually make Hitman one of the more interesting treatments of character and morality in games. It has a clear thematic vision which is reflected at all levels of play. But it’s an old, old vision, a reactionary and evil one which takes feverish pleasure in condemning the whole world as a hotbed of sinners and whores. Its inherited bigotry lends itself without much friction to the crude extremes of Absolution. They are nothing new—they’re simply louder.

In This Friendly, Friendly World

In This Friendly, Friendly World The Book of Unwritten Tales 2 (PC) game review

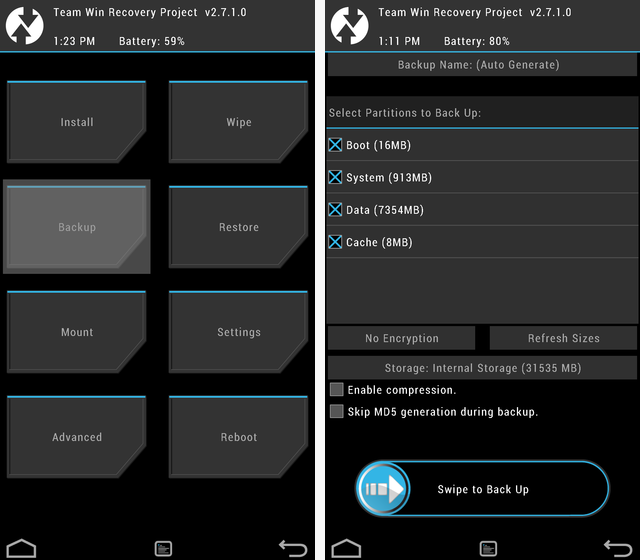

The Book of Unwritten Tales 2 (PC) game review How to View & Send the New iOS 9.1 Emojis on Android

How to View & Send the New iOS 9.1 Emojis on Android The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited How to - Beginner's Guide

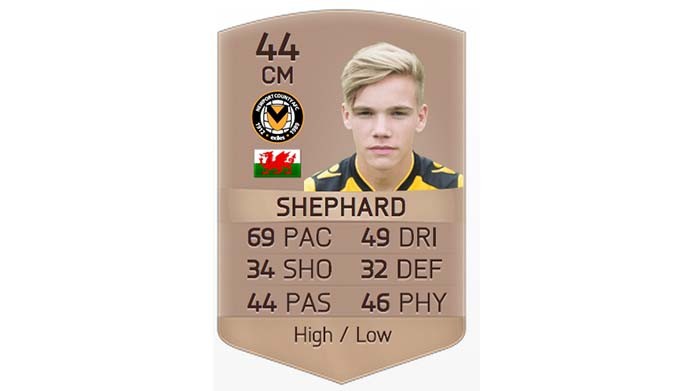

The Elder Scrolls Online: Tamriel Unlimited How to - Beginner's Guide FIFA 16: Worst and Lowest Rated Players - Ultimate Team

FIFA 16: Worst and Lowest Rated Players - Ultimate Team