I often say ‘cosmology’ when referring to the narrative gist of a game’s world. Throughout history, cosmology was the study of the nature of our universe in a broad all-encompassing way, with different thinkers inclining towards the physical, metaphysical, religious, or whatever other area interested them. A cosmological view such as Daoism, for example, might suggest a sense of spiritual harmony woven through all existence.

In many games, we’ve the benefit of being outright given an overarching narrative to bounce with the gameworld, and if it’s well enough crafted, you might feel the story and the gameworld fit each other so there’s a sense of narrative harmony – try to divide one from the other and you’d end up losing a lot of important subtext. BioShock’s Rapture is neat since its Objectivist principles are strongly relevant to everything the player experiences.

A game’s cosmology draws from design of its narrative, gameplay, levels, sounds, visual aesthetic, and on and on, since worldbuilding isn’t just the careful placement of furniture or graffiti inked in blood. It’s heavily dependent on the player’s ability to relate to this world in the sense of what verbs she uses or must refrain from using, and on the game’s plot to frame and contextualize the fictional world’s story events. If the player can jump yea high or can teleport, most level designers take this into account when building a city; how the player navigates the area, what she sees and feels as she does so, is key to the city’s feel.

Taking Dishonored’s Dunwall, your first glance tells you it’s a distortion of industrial-age London, all filth and grime over bleached pastels. A rat plague chokes the city’s population – bodies litter the streets and are dumped into the river en mass. All technological advancements of recent years have gone to protect the aristocracy and the city guard from Dunwall’s desperate, dying citizens, or to better mine available natural resources to fuel these defences. Oppression and disease wear humanity to the bone.

The natural world itself is hostile and distained by its human relatives. Great whales roaming the seas are skinned alive for their oil, knowing of the fact that their extinction will signal some dark global cataclysm. Recent years have seen hagfish, rats and river krusts flourish unfettered. The once-prosperous Flooded District sees the worst of these natural disasters. It becomes your home.

Those rich enough to dwell in comfort are treacherous, misanthropic souls through and through, your usual corrupt officials, decadent nobles and mad scientists. The common folk live in constant fear of the plague, of their betters knocking round to jail them, of the bogeyman you know exists. Your quest for vengeance (or justice) is assisted by this sinister figure’s gifts: access to dark magic and a horribly useful still-beating heart.

Early on, Dishonored unsubtly tells you the city will worsen depending on how chaotic you choose to play: the more people you kill, the more the plague will spread and the worse ending you’ll get. It tells you that aside from combat there’s always the non-lethal stealth option. But the game’s systems are heavily stacked to enable you to slaughter your way through each level – the vast majority of toys and powers available are all about killing people in cool and fun ways. And given the sheer moral desolation of Dunwall, who could blame you for succumbing to temptation?

If you opt towards being merciful, wrangling a way to spare the lives of each noble and official you depose in your mission, it’s much harder, thankless work. Every kill by accident or out of necessity feels heavier, every minute spent waiting in the shadows filled with indignant self-restraint. You fight against the world’s cosmology itself, hoping your attempt to be a good person might eventually make a dent in this horrible world.

In my time with it, looking towards Dishonored’s cosmology interested me far more than the game’s relatively humdrum plot. But examining a game’s cosmology can also help us figure out what a game is trying to do or through which lens we might benefit to examine it.

A common defence of the GTA series is that you don’t have to run over a sex worker to gain cash, and that these actions are more indicative of the player than the game. However, the major focus of any GTA is in enabling the player to be a low down dirty criminal. Crime sprees and reckless driving frame the majority of player-relevant activities (and are far more fun than following the rules of the road and standing around not shooting people). Peaceful activities like playing darts or eating burgers are a thin veneer over the games’ predominant anarchic systems. Whereas Dishonored always allows for a non-lethal approach, any attempt at ‘being a good person’ in GTA is inevitably thwarted by the next mission.

So while the player can choose to stop at every red light, or venture into the countryside and watch the sun go down, it takes a lot of effort to ignore the game’s entire raison d’être: to breed chaos to your heart’s delight. In examining whether the game encourages violent attitudes or fails at satire, it’s vital to consider GTA’s cosmology and how it invites the player to participate within in.

The entire Metal Gear Solid series is devoted to a long-spanning political and philosophical war stuffed to the ears with bonkers characters and preposterous plot twists. Were it stone-faced in its delivery it would be just another military-infatuated action hour, but it embellishes every other moment with some silly joke or ridiculous camp flourish. Beneath all the political intrigue it’s at heart an absurd romp, an existential gag, like a clown funeral. It’s so intensely silly, so it imbibes the narrative that even if nothing about the story makes any sense, that’s ok, because the world doesn’t make any sense anyway.

DigiPen’s Perspective you can play it here and you absolutely have to because it is brilliant and I’m going to spoil it a bit) relies on cosmological trickery for its entire twist. The player is repeatedly stepped out from one existence and into another more encompassing one. The mechanics contextualize the game’s title for you, assuring you it refers to spatial awareness before subverting expectations and toying with your fundamental notions of the in-game reality.

Although Perspective plays with a seemingly linear narrative, the use of hierarchy spins it around temporally, since these two realities are actually co-temporal but exist within a reality that is after this other, later reality. It’s a narrative that is very much read from between the lines, and you can only really enjoy the twists by looking at Perspective from a cosmological angle.

Kim Jong-un’s Glorious Missile To Liberate The Nations DX presents a world where North Korea is the chirpy benevolent underdog. The missile you control flies smoothly and gracefully in your attempt to preserve your neighbour’s wildlife (it’s easier if you glide as high up as possible), but becomes jagged and frantic when met by hostile western landscapes and military. Fortunately, our supreme leader is gracious in allowing you three spare missiles. And should you fail, Kim Jong-un can’t even look at his modest North Korean meal for the tears in his eyes at the western nations’ continued future enslavement. Such a kind-hearted man, but just, since you’re told you will suffer eternal punishment. As a farce it succeeds beyond GTA’s best attempts.

Formalizing a game’s cosmology can be very useful as a way to consider a gameworld's narrative holistically and to frame in-game actions within this context. So long as we discuss a game’s plot or the relevance and meaning of player actions it’s handy to have this reference point, as it can give the lie to a character’s beliefs or reveal great depth to something otherwise innocuous.

Stephen Beirne is a freelance games critic and professional human. You can find more of his writing on his site Normally Rascal or by following him on Twitter @ByronicM. If you liked this article, you might consider supporting his writing by visiting his Patreon and becoming a patron.

Gears of War 3: The Gameranx Review

Gears of War 3: The Gameranx Review For One Day Only Get an Additional 15% off All VPN Services!

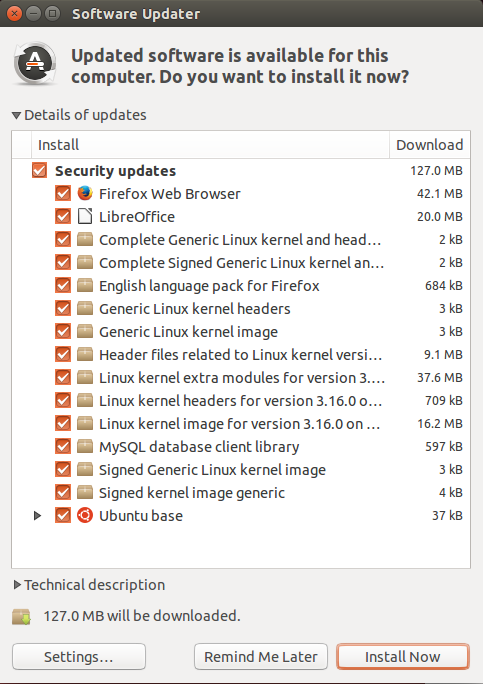

For One Day Only Get an Additional 15% off All VPN Services! How to Overcome Problems with the Ubuntu Update Manager

How to Overcome Problems with the Ubuntu Update Manager Top 13 Tips and Tricks for Newbies in Civilization: Beyond Earth

Top 13 Tips and Tricks for Newbies in Civilization: Beyond Earth FFXV Episode Duscae Demo: Phantom Swords Location Guide

FFXV Episode Duscae Demo: Phantom Swords Location Guide