This is the follow-up to our interview with Irrational Games writer Drew Holmes on the upcoming BioShock Infinite. Be sure to read the first part, which covered the iterative process in developing the game.

There's a myriad of differences between Bioshock and Infinite and apart from Elizabeth, Columbia and Christ knows what else, is that Infinite is the first Bioshock game without a silent protagonist. I've always found it to be notoriously difficult to get a first person character just so. Unless it's nuanced and measured, when a character says something even slightly different to what the player thinks, or feels, at that particular moment, then the immersion is lost to wind and time. I ask what sort of challenges Irrational face when going from a silent protagonist, to a voiced, fully-realised character.

Drew Holmes: Stepping back for a second, in terms of the reason behind it. Jack, in Bioshock, his purpose in the story is to be the silent cipher, integral to the WYK stuff. This time around we're not repeating ourselves, we're trying to do things and one of the new things we wanted to do is have a character, for this story Booker had to be a real character and had to interact with the world, and he had to have a history, so I think you start there.

An obvious, but nonetheless necessary point to make. A bonafide character struggles to be a character without a voice, Gordon Freeman notwithstanding.

DH: For a while, as you write Booker and you want to keep him silent so that people can bring more themselves to the world, but he's talking, and we were doing some playtesting with some external people and what we were finding is that at that time, people felt that Booker wasn't talking enough. They wanted to hear more of him, and I think because he is a character that has a history, people want to know more of his opinions.

From the time I spent, Booker didn't exactly wax lyrical, but that was largely due to the fact he was alone, or at least keeping to himself, and it worked, it made sense and he felt genuine. But let's al l sit and consider whether Ubisoft had the same issue with Jason Brody in Far Cry 3.

DH: So I think the cipher angle, of the immersion, was interesting because we were essentially getting that players didn't feel immersed enough because they didn't have a better sense of who Booker was. Dome of the stuff he was saying couldn't be trusted and people were thinking he was holding back information that the player should've shown earlier, which wasn't the case. So we went back and made some tweaks to the game so people got a sense that what Booker says, you can take it at face value. He's not holding anything back from them. But yeah, it's ultimately it's a lot of trial and error, and it's focus-testing and relying on your gut.

You get a lot of focus test data back and a lot of times it says the player doesn't like this part of the game and you've almost got to work like a detective to figure out what the root cause of that is. There was an example with Liz, early on, we'd done all these things with Liz and we'd built her up to be this fully realised character and the AI worked great and she was helpful in combat and all these wonderful things, But we were getting this feedback that people didn't connect with her in the way that we were connecting with her. You trace it back to this very small thing that happened shortly after you meet her and her reaction to something that Booker does was at the root of it, immediately forcing people to say 'what did she do this thing that doesn't make-' it just sticks in their brain and eats and them. So we went back and we changed her reaction and all of a sudden, people loved Liz. That one, single, tiny thing. So we've really got to be mindful and listen to the feedback that we're getting, then really start to analyse what's at the root of the problem.

The perennial problem of the AI companion, more often the irritating little shit perched upon a shoulder than an actual person. Alas, no meeting with Liz so I cannot begin to comment, but interesting nonetheless.

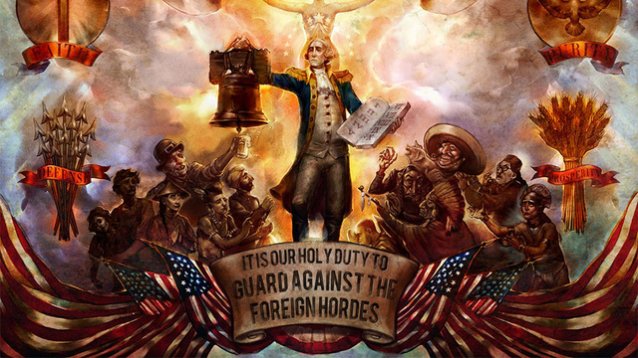

One of the main things that struck me about, and a lot of people, in the hour of Infinite I played is The Raffle. Without sauntering in to spoiler territory too much, as this scene should be experienced as unblemished as possible, The Raffle explores Columbia's racism and explores it hard. If game explore racism Games then have a tendency to approach it in an indirect sort of way, look Skyrim, or Mass Effect and you have racism, but it's Salarians and Elves. That's not to say it's an indictment of those games, by any means, as it befits the context of each perfectly, so I ask he he thinks there's a particular reason why others developers don't want to explore racism in such a head-on fashion?

DH: In terms of what other developers are doing, I can't really speak to it because I don't know what it's like on the ground there. I do know that our viewpoint is that there's no such thing as something video games can't talk about, or something video games can't do. I think you have to respect games as an art form and as a medium, and there's no reason you can't tackle any of these more mature themes you see in books, TV or film. Games shouldn't be any different and I think as far as the way we have chosen to tackle the subject head-on, it goes back to creating a world that feels authentic and setting the game in 1912, if you're not willing to address those issues, racism in particular, then it doesn't feel authentic and you're already going to have players immediately feel that something doesn't feel authentically 1912. On top of that, I think that we're not putting these issues in the game to exploit them. It's not meant to be salacious, it's there because the story and the characters require it. It's so engrained in the culture of Columbia, who Comstock is and what the story is, that to remove that aspect lessens the experience.

But a conscious decision was made, from the outset, to set a game in 1912, from a city borne of the Columbia Exposition at the Chicago World's fair. (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86088452/1893-05-12/ed-1/seq-2/ & http://www.loc.gov/rr/news/topics/worldsChicago.html – a very apt image and appropriate source) A time and place widely regarded as the ground zero for the emergence of American Exceptionalism and if you didn't have the racism, Infinite simply wouldn't be a game about American Exceptionalism.

DH: It wouldn't be about a lot of things, in the same way that if you look back at Bioshock, the example we use is and always bring up is with the Little Sisters. The save and harvest of the Little Sisters was infanticide, that's pretty much as taboo a subject you can get, but when you actually play the game and understand, within the game, what the context of that is and you finish the game and step back, can you imagine Bioshock without that choice? I think in the same way that when people play Infinite, and they see what the story is and they see how, not just the racism but religion, the class warfare that happens in the game, that it's so engrained in the DNA of the game that when you finish it, you can't imagine any of those elements not existing.

And then it died again. Thankfully, I'd just about run out of time. Phew.

I hope that went some way to alleviate the crushing weight of expectation and anticipation Bioshock Infinite has laid upon itself as because even with only a handful of loose playtime clanking around in my pocket and Drew's dulcet tones still echoing off the walls of my brain, Infinite may well be precisely what we were hoping for.

Mind Blown: 40 Final Fantasy Secrets & Facts

Mind Blown: 40 Final Fantasy Secrets & Facts Grammy 2015: Sam Smith and Pharrell Williams join the gala

Grammy 2015: Sam Smith and Pharrell Williams join the gala Fallout 4 Chems Healing Effects, Cure Drug Addiction

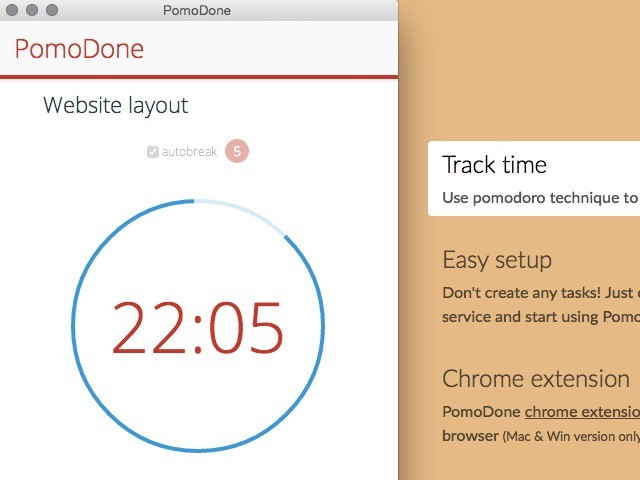

Fallout 4 Chems Healing Effects, Cure Drug Addiction Add Pomodoro Timers to Your To-Do Lists With This App

Add Pomodoro Timers to Your To-Do Lists With This App Review: Wasteland 2

Review: Wasteland 2