“And if it is evil in your eyes to serve the Lord, choose this day whom you will serve” – Joshua 24:15

If the motivating theme of El Shaddai is the human necessity of choice, the game then must present the player with clear options. In my last piece, I talked a bit about the nature of that choice. But the game does something very clever to drive home the implications of those choices. It embeds the two options – either serve God, or serve humanity – in the two primary characters of the game: The protagonist Enoch and the protagonist and player’s guide, Lucifel.

I appreciate El Shaddai for its ambiguity; it is determined to allow the player to make up their own mind about where they stand. But it’s not ambiguous about the nature of that choice. Though the choice may seem difficult, the options presented are no less stark.

El Shaddai is in no mechanical sense a sandbox game, but it does provide a kind of sandbox for the player to act out various beliefs and presumptions about the world.Those choices are helpfully personified in the two main characters of the game, and by being allowed to play as Enoch, the player is forced to “play” with the idea of devotion to God over all else. In other words, the player is allowed to “play” with the idea of faith. El Shaddai is in no mechanical sense a sandbox game, but it does provide a kind of sandbox for the player to act out various beliefs and presumptions about the world.

Enoch is introduced by Lucifel in the intro to the game as a “pretty good guy,” but the goodness of his character goes much deeper than that. The Old Testament account of Enoch merely says:

“After he became the father of Methuselah, Enoch walked faithfully with God 300 years and had other sons and daughters. Altogether, Enoch lived a total of 365 years. Enoch walked faithfully with God; then he was no more, because God took him away.”

Here was a guy who was so faithful, so theologically evolved, that God was like, “Okay, you’re ready,” and gave him the luxury of being the first to be raptured. The implication here is that Enoch was so on-board with the faith that he had no need to prove his devotion any more than he had already.

Then again, by taking him up to Heaven, God was helping him believe. He was keeping him for himself. And Enoch was happy there. He was a scribe for God, a writer who devoted his writing to his glorified Master.

Probably the defining quality of Enoch, then, is his willingness to do anything God asks. Much of the game is spent “purifying” angels, demons, and lost souls, basically beating them up until they evaporate. It’s not up to Enoch, or the player for that matter, to know where they go after that. He’s been given a job to do, so he follows through. When a command is given to him by his creator, he sees no need to question it.

But Enoch isn’t perfect. He struggles more and more with doubt the more he comes in contact with the ‘real world’. In a sense, he is sheltered. He’s spent most of his life unaware of certain truths about the world – not that there were people who believed and lived differently than him, but that they are happy doing so. It’s a truth that shakes him, especially when he sees the way his own faith often puts an end to that kind of happiness.

As Enoch progresses through the game, his crisis of faith becomes more and more pronounced, until God is literally forced to freeze him for several years while he makes up his mind. Enoch’s primary catchphrase, uttered every time he dies and is brought back to life is, “No problem, everything’s fine.” At first, it feels genuine, but as time goes on, it feels more and more forced, as if Enoch is saying it to convince himself more than anyone else. Forced repetition of supposed truths is an exercise any religious person is familiar with. Here, it’s what keeps Enoch moving forward.

But one reason he struggles is Lucifel, who despite being officially positioned as God’s right-hand man ends up subtly subverting him at every turn.

Here’s the thing about Lucifel (and bear with me, this is weird): He’s God’s primary helper, with the power to move through time. In the future, he will become better known as “Lucifer”, the fallen angel who wanted to be like God and led an army of angels in rebellion against God and his heavenly forces. As a being that lives outside of time, Lucifel is well aware of all of this, and at the given moment he is holding his cards close to his chest, only tipping us off when he subtly attempts to subvert Enoch’s mission and devotion.

Lucifel is appointed to be Enoch’s “guide” throughout the game, ever-present, talking directly to God (via a cell phone) at every save point. We hear only one side of the conversation, though, and we get the sense, in the way that Lucifel often seems to be talking down God from his own worries and doubts, that his relationship with God is one of equal power. In fact, it often seems like Lucifel is the reasonable one, the guy who’s left carrying out God’s seemingly insane plans while God simply makes declarations without thinking them through.

But Lucifel is almost certainly up to something. At every turn he seems to be calling into question God’s promises and intentions. His affection for worldly clothing betrays his preference for an overall worldly aesthetic and philosophy. Lucifel is not to be trusted.

Unless, of course, you’re on his side. And that’s the funny thing about El Shaddai. By the end of the game, your mind is pretty much made up about whether you relate most to Enoch or Lucifel. Personally, I found myself on Team Enoch (more about that next week), but I’ve talked to a number of those who saw Lucifel as obviously in the right. Both sides are, as El Shaddai demonstrates, perfectly reasonable. But only one side can be right.

We’re given examples of two ideological paths: the believing and devoted hero, or the rebellious and pragmatic anti-hero. While the game does seem significantly invested in Enoch’s plight, and therefore seems to come out, in the end, on the side of God, it nonetheless seems to subtly imply that we’re only seeing one side of the story. All Lucifel needs is some time, and then he’ll start telling us the real truth. El Shaddai provides the player with fleshed out characters faced with living out their own view of the truth. The question left for us to answer is which of the two we admire most.

PS Vita error code NW-13347-8 fix: unable to connect to the PSN using Wi-Fi

PS Vita error code NW-13347-8 fix: unable to connect to the PSN using Wi-Fi Pick A Disease & Wipe Out Humanity in Plague Inc.

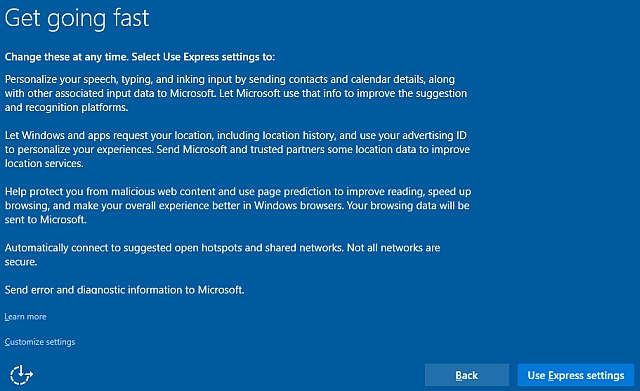

Pick A Disease & Wipe Out Humanity in Plague Inc. How to Configure Windows 10 Privacy Settings During Setup

How to Configure Windows 10 Privacy Settings During Setup How to get Forza Horizon 2 Skill Points for Xbox 360 and Xbox One

How to get Forza Horizon 2 Skill Points for Xbox 360 and Xbox One How to unlock Infinite Health in God of War III Remastered

How to unlock Infinite Health in God of War III Remastered