I remember from back in college the nature of conversation according to Roger Scruton, philosopher and despicable git. Scruton wrote how the art of conversation was dying: conversation is supposed to be enjoyable, frivolous, not motivated like an interrogation or an interview. He compared it to the act of play, as with a child who plays simply because it’s fun and not because of side-effects like productivity.

Scruton framed his arguments as critique of hectic modernity where everybody’s always busy and mainly converse to optimize their commute efficiency or establish social networks and the like. The details may be off or I maybe misremembering completely. Nevertheless, at the time I took a disliking to his stance, if not because of his rancid classism then at least in disbelief that conversation was ever this sublime transcendence, and not, say, a mode of communication.

Videogames, on the other hand, have largely drifted towards the extreme opposite. Rather than conversation being a thing that players enjoy, I get the feeling that it is generally thought to detract from the point and the joy of a game.

Think for a second about the role that conversations usually play, at least in the domineering AAA model. Specifically, think about longer exchanges of dialogue, rather than anything that could be pasted into a twenty second trailer. Typically conversations motivate the next mission and serve to debrief. They justify plot structure and convey information to the player on objectives, game rules or as worldbuilding elements. They prod you to relate to characters, endearing them or delineating the character for a distinct narrative purpose – if you don’t like this damsel, it won’t mean anything when you have to save her. And the more these functions are ingrained into gameplay segments (like where characters natter while the player plays) the less they ‘get in the player’s way’.

Good designers aim to substitute gameplay in place of operative conversation. And for figuring out ludological solutions to a narrative problem, fair play to them.

But why are conversations considered a narrative problem? Are they too ‘un-game’, meaning not interactive enough? Or hazarding a guess, might it be because putting words in the mouth of the player-character risks jarring the player from the game? Or might it be that writing a good conversation is hard?

The way conversations are treated as functional and as design obstacles to be overcome makes me wonder about the disconnect between narrative and gameplay. We still haven’t quite shed the ‘gameplay versus narrative’ baggage of ye olden days: when conflict arises between the two, good design dictates that gameplay should win out. Since conversation seldom involves shooting, stabbing and jumping – the gameplay language of the AAA model – it’s deprioritized. And it’s often surmounted in interesting ways.

One big solution is the silent protagonist. Nip the problem in the bud - no need to worry about the player rebelling against narrative teleology when the protagonist has little narrative agency. For many, the silent protagonist maximizes their potential to immerse themselves in the gameworld without the pesky squawking of a dissociative personality.

For me, in most cases, the downside is the game then feels like one long fetch quest, except instead of wolf pelts I’m arbitrarily fetching humanity’s salvation. The presumption of married agency can also work adversely: Half-Life 2 wasn’t improved by Eli Vance solemnly describing my Gordon Freeman as Earth’s last hope, and all the while I mockingly twirled around the room, singing “lu lu lu.”

Although occasionally used appropriately, the silent protagonist is often a crutch to excuse an absence of energy to write a player-character.

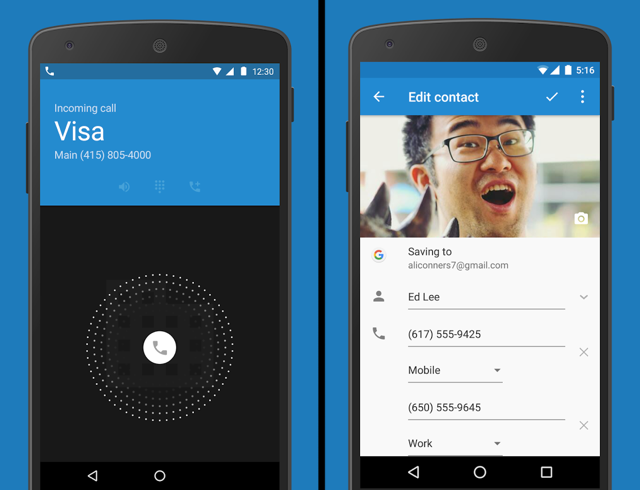

Another popular solution to conversations is the dialogue. Extending interactivity into conversation helps excuse longer conversations to the player, even if the end gamestate is unaffected by dialogue choices. Of course, a narrative still can’t account for every desirable dialogue choice, but so long as it hits all the reasonable beats most players will make concessions.

Truth be told this often works wondrously. It allows leeway to the player without diminishing the player-character à la the silent protagonist.

Some games, however, like Mass Effect 2, imbue conversations with traditional ‘gameplay’ designs, treating character interactions as obstacles to overcome and opportunities to level up. The Paragon/Renegade system is rigged to instantly solve any relationship problem at the push of a button: deus ex dialogue. It’s design tailored to those who only see value and meaning in systems through whatever toy results. Filling up your bars to win a social dilemma gamifies narrative to justify it within formalist definitions of the medium.

I can’t imagine Roger Scruton would be terribly pleased with conversations being so goal-orientated, so utilitarian. Nor am I terribly pleased at this notion that characterization even warrants solutions, as if teleology manifesting through dialogue is more problematic than that manifest mechanically.

The source of the “problem” lies in a double standard between narrative and gameplay. It’s safe to say most players have reconciled the fact that Sonic won’t plant a tree or hug Robotnik no matter what buttons you press in the Green Hill Zone. Unless they release DLC, Booker Dewitt will never fry up an omelette and Scott Shelby won’t shoot crows at people. Although the exact extent to which Murder of Crows is used in BioShock Infinite is partially governable by the player, everybody still knows that they can only act when they’re allowed to. We’ve all long since reconciled that the player is bound to the devs’ teleology in this respect, although we enjoy the game more the less it’s said.

As we play, the verbs we expect are thematically bound to the core gameplay. Early into any game we rationalize that player actions will largely revolve around these established mechanics –BioShock Infinite is mostly shooting, whereas Heavy Rain is more context-orientated. Using our imaginations, we can extrapolate the core verbs to imply nuance, so shooting can be aggressive or playful. And because we expect them, we’re accepting of the limits on our actions, within reason, rationalizing it as Booker mostly shoots because he’s a shooting type of guy.

On the other hand, dialogue is just a bunch of words, and if Booker can say those words and intone like so, the array of dialogue options for him opens up. We’re accepting of the action limitations born from mechanics, since running and flying are worlds apart mechanically, but we don’t hold conversation in the same esteem, perhaps because the character is shown to know the words and social cues from before and could feasibly express them in different combinations.

With a stock of words easily at-hand, dialogue seems so potentially flexible. To the anxious designer, the player’s attitude towards the narrative is the sword of Damocles.

Except, if we’ve grown accustomed to projecting subtext onto the player-character via mechanical limits, why expect that characterization depicted through dialogue should limitlessly cater to us in a way mechanics don’t?

The rationalization of character actions hinges on adopting a soft determinism to justify narrative context – Booker is a thug, a soldier; Shepard is military-bred – which is a philosophy of action just as applicable to people in reality. They act this way because, well, they are this way. It’s existentially satisfying to draw a causal line between our deeds and our soul; it helps us own our actions.

In truth, words are no less determined. Verbal communication isn’t a raffle of signifiers, it’s a form of expression causally linked to the speaker’s identity. The meaning inferred is an expression of their character at that moment in time. Even accidental meaning reflects character, like Kenny’s prejudices against Lee in The Walking Dead. If someone’s actions are determined and limited by her character, so too are her beliefs, opinions, and dialogue.

Despite all the energy invested in finding work-arounds for dialogue and conversation, we already know all this, at least deep down. So long as a character remains distinct and compelling, we accept their words and their deeds as fixed beyond our input. When done well, dialogue trees demonstrate our propensity as players to assent to narrative limitations – I can’t think of a single conversational option in TWD that did not feel “Lee Everett” enough.

Moreover, the same goes when you remove player choice. Hotel Dusk revels in the best dialogue in any game I’ve experienced, due to the fact that the characters speak and interact like real people. They’re not mission objectives, not parrots of exposition. Conversation turns naturally; it’s enjoyable without the need for gamifying bells and whistles.

Narrative-heavy (read “dialogue-heavy”) games like Hotel Dusk, 999 and Phoenix Wright aren’t special exemptions from the medium. They work because player enters an understanding that this will be the narrative mode, and they do their best to reward the player with enjoyable conversations, rather than through grinding for conversational XP. And if the conversation is interesting enough, we don’t actually need it to be broken up every ten seconds with another bloody shooting segment.

The art of conversation need not be such a scary thing for game designers, nor should it be relegated to the repertoire of niche titles. It’s another tool available to storytellers, and it can be very useful, very fulfilling, if practised and honed and given the chance. Shunting it aside as a ‘not game enough’ way to wax narrative serves only to foster a limiting, reductive attitude as to what a game can be.

Euro Truck 2: most famous 18 Wheeler truck games

Euro Truck 2: most famous 18 Wheeler truck games The Forest PC game Fix for Crashes, Black screen, Slow loading, No sound, Cant Save, Textures issues

The Forest PC game Fix for Crashes, Black screen, Slow loading, No sound, Cant Save, Textures issues Dead Space 2 Multiplayer Guide

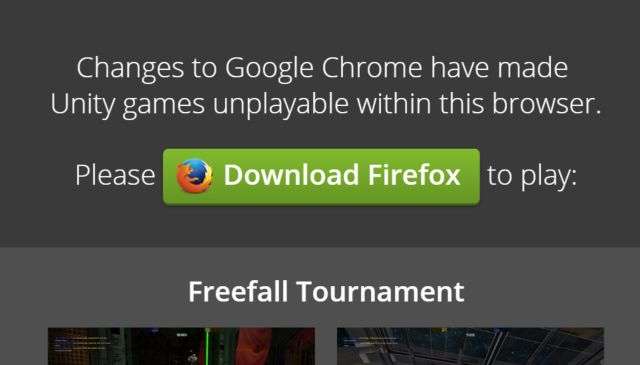

Dead Space 2 Multiplayer Guide Download and Run Your Favorite Flash Games Before They Go Away

Download and Run Your Favorite Flash Games Before They Go Away Minecraft (PC) Update 1.9 - Combat against the Ender Dragon

Minecraft (PC) Update 1.9 - Combat against the Ender Dragon