Like Hideo Kojima’s prior work, Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes opens with a claim to videogame auteurism, confidently assuming the artistic import of the introductory text “A Hideo Kojima Game.” Videogames frequently invoke the auteur temperament of cinema, placing credence in the authorial vision of a singular author and further bridging the influence of one medium on another. Occasionally, opponents levy criticism against the increasing cinematic influence on videogames and against cutscenes in particular, charging that this passive storytelling device robs the inherently interactive quality of the medium. Such a claim, of course, severely limits what videogames can do and blatantly ignores the reality that all artistic mediums borrow from and are in constant conversation with one another. Moreover, the criticism disregards the artistic wealth of videogame authorship, because cutscenes shift the storytelling agency away from the player and back to the developer’s unrivaled vision of the narrative. The cutscene’s vacillating control over narrative agency remains a fundamental tension unique in videogames, building upon – and not simply borrowing from – the work of cinema.

The impact of cinema on videogames endures as a contentious topic in current criticism, often left wanting for substantial answers. A curious take by Chris Priestman on Kill Screen grapples with the question of what makes videogames cinematic, directing attention to how cinematic language like the jump cuts of Thirty Flights of Loving or the split-screen visuals of Unmanned reflects how videogames can refashion existing devices of another medium within the parameters of its own medium specificities. He goes on to claim that the Metal Gear Solid series stumbles at merging both mediums, insisting, “There’s a very distinct difference between the lengthy cutscene and playing as Solid Snake.” But after playing even just the first few minutes of Ground Zeroes, one can spot Hideo Kojima’s playful awareness and rethinking of these distinctions given his reputation for stylized, extended cutscenes. Like the aforesaid jump cuts and split-screen visuals of other games, Kojima maps an initially cinematic technique onto the language of videogames – the uninterrupted long take – and begins collapsing the barriers between mediums altogether.

The opening cutscene maintains the ongoing continuity of real-time narrative flow, refusing to cut to another angle in favor of simply gliding through space as though from the perspective of an invisible camera operator within the sequence. Hideo Kojima recurrently indicates the pervasive influence of film on his entire body of work, not only in lifting a composition by Ennio Morricone for this sequence or even just snatching the name “Snake” from John Carpenter’s Escape from New York, but also in reserving a markedly cinematic quality for rendered cutscenes. The indebtedness to John Carpenter is especially noteworthy in Ground Zeroes, as the opening cutscene’s unbroken ten-minute single take that follows the menacing journey of a skeletal war criminal and his secretive band of soldiers through Camp Omega recalls the extended opening take of Halloween’s equally enigmatic passage through nighttime space. As in Carpenter’s probing camera, Kojima swivels and swoops his simulacrum of a first person perspective between characters, into expressive close-ups, in and out of vehicles, and in graceful arcs even as it shudders like a handheld camera present within the scene. This shaky, on-the-ground quality lends the camerawork a stylized appeal certainly reminiscent of John Carpenter, but also in the roughness of Alfonso Cuarón’s camera in Children of Men or even in the constant movement of Orson Welles’ glides in the beginning of Touch of Evil. In terms of videogames, the single take through a militarized zone evokes Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare’s riveting opening credits tour through a city in the midst of coup d’état, with Kojima’s camera lingering on similar visuals of prisoners knelt before armed guards and expressions of military power.

Aside from the impressive stylization of camera movement through space, the sheer visuals of the sequence alone underline the tight artistic direction of a developer confident in his craft. Hideo Kojima sets the scene in an expressive thunderstorm that cloaks the landscape under cover of darkness, veiling the harsh, overbearing glare of guard tower lights through the glint of rainfall. Long shadows and faceless antagonists cast an ominous tone for the game, informing the attitude with which the player will come to experience actual gameplay. Indeed, it’s in the blend of camera technique and rich visual expression that renders the work of a cutscene so integral to the game. Kojima remains cognizant of the differences between cutscene and actual gameplay, but he’s also more interested in bending these distinctions and foregrounding how both come to play important roles in the experiential whole. Cutscene and gameplay are not in conflict with one another, but exist as part of an uninterrupted, fluid narrative that delivers vital expository information and a palpable sense of tone. Moreover, Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes employs its single take cutscene as a temporal device that unbrokenly bridges one sequence to the next, linking entire worlds and sculpting through time.

This temporal playfulness is especially apparent when Kojima detaches his camera from the magnetism of Skull Face only to find Big Boss/Snake lurking on nearby seaside cliffs. The moment represents a transferal of camera consciousness from one subjective perspective to another, and the game, still ongoing in its long take without any cuts, enters into the third person camera of gameplay. In linking the single take of the cutscene to a smooth transition in full control over Big Boss, Kojima maintains the fluid continuity of an unbroken perspective, deftly meshing the world of the cinematic to gameplay. It’s a profound, understated gesture that acknowledges the single take camerawork and lack of montage inherent in gameplay, recognizing the capacity of videogames for “a level of fluidity not seen in previous visual media like film or television. Abandoning montage creates the conditions of possibility for the first-person perspective in games… even if the game itself is a side-scroller, or a top-view shooter, or otherwise not rendered in the first person” (Galloway 65). After all, when playing a videogame, the camera remains affixed to the player-character without interruption by montage (with a few exceptions, i.e. Thirty Flights of Loving, some survival horror titles with predetermined framing, etc.), leaving the experience of gameplay grounded in real time.

The continuous progression from cutscene to gameplay renders the experience of playing through Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes a Bazinian exercise in videogame realism. My final playthrough of the game was a completely unbroken experience without dying, rendering the entire game from the opening cutscene to the final extraction by helicopter one continuous, sixty-minute excursion. To charge the infusion of cinematic techniques in videogames as detrimental totally discounts the realm of possibility for artistic expression. Cutscenes in particular remain useful, but never entirely obligatory, tools for authors in service of the narrative and overall experience of the game. Discouraging the use of cutscenes confines art to arbitrary parameters and stifles the creative capacity of those developers looking at all avenues in conveying meaning. Hideo Kojima’s effort in Ground Zeroes crafting a strikingly elegant single take and seamless transition into gameplay allows us to not only see the kinship across mediums, but to feel the sculpted contours of authored visual fluidity. That’s the ultimate appeal of the Metal Gear Solid series, highlighting the tension between player agency and authorial direction, the fundamental essence of all videogames in history. Here, this tension becomes liquid, allowing us to effortlessly inhabit both within and without – both in the same instant.

--

Works Cited

Galloway, Alexander R. Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. Print.

--

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on First Person Scholar, Thumbsticks, and Medium Difficulty, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.

Where to Find All 60 Collectibles Location in Star Wars Battlefront

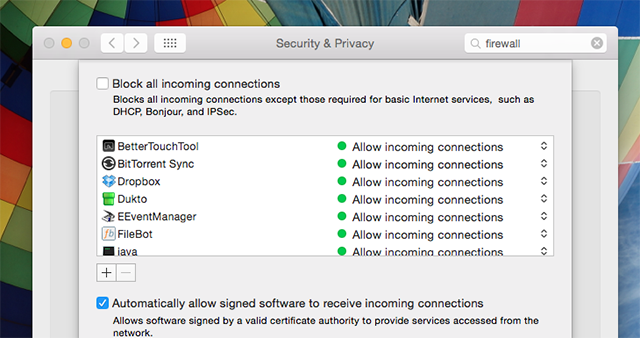

Where to Find All 60 Collectibles Location in Star Wars Battlefront Fallout 4: How To Access Secret Dev Test QA Area Using COC QASMOKE Console Command

Fallout 4: How To Access Secret Dev Test QA Area Using COC QASMOKE Console Command Best ways to earn Glimmer in Destiny beta

Best ways to earn Glimmer in Destiny beta The Easiest Way to Fix Blurry Fonts in Windows 10

The Easiest Way to Fix Blurry Fonts in Windows 10 Football Manager Classic 2015 review

Football Manager Classic 2015 review