Note: Gunpoint spoilers within.

On the surface, they couldn't be more different. One's a micro-budget indie game with a bit of buzz behind it. The other is Sony's big first-party hope for PS3 this year, which has had more money poured into it than Scrooge McDuck's swimming pool.

But, having played both in the last few days, I noticed how quickly (and easily, it must be said) they grab the player's attention. Specifically: the introductions to both games are superb. There's no ponderous wading-through of overlong cut-scenes or hand-holding tutorials. They get players engaged with a speed that embarrasses rivals.

I can't talk too much about The Last of Us, as I'm under an embargo that would make the Cuban Missile Crisis look like a spat in a kindergarten playground. I can say, however, that it's so well executed people will be talking about it for years to come – including ourselves, in a dedicated feature on it after it comes out. It's that good.

Gunpoint, on the other hand, has no such embargo, and I'm glad for that. Because it's ace, and I can blabber on about why it is so, at least to me. Developed by Tom Francis, it's been on the radar of many since it was announced. The setup is this: you are Richard Conway, a freelance spy-for-hire who is framed for the murder of an office worker. It's your job to infiltrate various buildings, recover precious data and solve the mystery of how you became so wrapped up in it all.

How you do this is up to you: violence, hacking, sneaking, all three. As you progress, security systems and human opposition increase in complexity and number, and one shot kills. Before long, you'll be hacking grid-based security nets where, say, the light switch is connected to the same circuit that opens the door you need to get through. Setting off a chain reaction (or tricking your enemies into doing it for you) becomes increasingly paramount, leading to some clever (read: taxing but ultimately worthwhile) puzzling. It's out next week. Buy it.

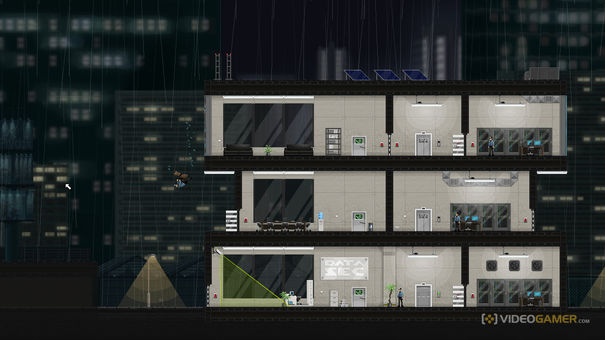

Anyway, back to that first screen. It is excellent, setting the tone with ease. The game's systems can become complex later on, but this first taste is all about atmosphere. Two buildings – cross-sectioned so the players can see what's going on in their many rooms - face each other on a dark night: the sort of night we'd describe as noirish, if our wank hats were to hand (they're in the wash). Suddenly, a figure – wearing a rain mac and fedora, small against the backdrop – comes smashing out of the left building's high window, before crashing off of the opposite structure's wall and through its first floor roof skylight.

As entrances go, it's one of the most memorable I've seen in a while. It didn't make me think 'f**k yeah' or whoop like an American journo at E3, but instead snatched my attention faster than Eastern Europeans on Liam Neeson's family.

A woman in the opposite building calls, asking if it was indeed your good self who had recently propped up Everest windows profits for the year. No is the answer, of course. He is, in the words of a certain mad doctor, after all, a professional.

The chat continues. As it did so I found myself staring at this little man, asking 'how did he survive that jump/fall?' and ruing his raincoat, wishing mine hadn't been taken away by the police. Amongst all this, I barely notice the assassin stalking the top floor. In fact, I don't notice at all, until I hear another window smash, the phone go dead, and the woman fall to her doom.

The assassin jumps out and finishes the job before scuttling off. As for Conway, he just stands there. I wasn't exactly shocked - a word I'd reserve for instances such as 'videogame journos stop moaning' or 'footballer shows humility' - but I was engaged.

Engaged because I'd been taken in by the style, and the questions posed by the beautifully-animated, attention-kidnapping fall, to even notice that the killer was in the building the whole time!

Narratively, this brief few seconds sets up the rest of the game, but it's the expert way it grabs players that means they actually want to plow through and find out exactly what's going on. Lots of games think they have to nanny players, immediately asking them if they know how to look up and down, asking if we know where the crouch button is, and would sir like to crawl under suspiciously out-of-place beam to prove it?

This doesn't. The Last of Us does much the same, even though it's completely different. Both have solid – if pretty tired – premises, but crucially both know how to capture your attention. Which, in a world of try-hard, shoot-bang, HOLD DOWN Y TO LOOK AT EXPLOSION PLEASE LOOK PLEASSSSSSE, is surprisingly hard to do.

Why Star Wars is dead to me

Why Star Wars is dead to me Half Life 2 & Source Engine Tweak Guide

Half Life 2 & Source Engine Tweak Guide In The Spin: Ten of BioShock Infinite’s Unanswered Questions

In The Spin: Ten of BioShock Infinite’s Unanswered Questions Fighting the Future: Jan Klose on The Surge

Fighting the Future: Jan Klose on The Surge .s picks of E3

.s picks of E3