You've killed a lot of men, admit it. You've killed a lot of women, too, except only really recently, when Activision cleared female soldiers for combat duty. Dogs, too, even though in actuality you probably value animal life higher than human. But they were asking for it, snapping and snarling at your throat all the time. You killed all your targets savagely, riddling them with bullets or slitting their throats with a blade. Maybe you even blew their limbs off in World War II, back when that sort of thing was morally justifiable, and you probably even whooped a little as you did so.

Your digital body count is not only something of pride, it's something that you're actively encouraged to improve upon. K/D is expected to increase exponentially, like some sort of demented, alternate-reality stockmarket run by…wait...no it is actually run like that. But, of course, there's a clear line between reality and fantasy. You didn't really kill all those people, and there's a definitive marker between what is only possible in games and what isn't.

Unless, of course, when there's not. While ARMA III and Battlefield 4 may well be pimping their own versions of military 'realism' (via the respective merits of heavy strategising and straight-up impressive visuals), it's a six year-old title that best represents the modern face of war. And it is chilling in its effectiveness at blurring not just the line between real and not, but also representing how a TV screen and reductive language change the horror of war into dispassionate busywork, in the game or otherwise.

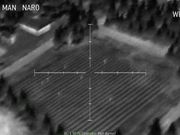

That mission is Death From Above, COD 4's AC-130H-based stage that sees you commanding the aforementioned killing machine. Presented solely in grainy, low-fi, 'white' or 'black hot' night vision, its lack of visual polish has the seemingly counter-intuitive effect of bringing it utterly in line with the real-life footage we've all seen, of laser-guided bombs and rattling chainguns destroying targets.

For a game huge on bombast, set-pieces and just out-and-out nonsense, Death From Above is a marked deviation from what comes before and after. As the plane's 'TV operator'/gunner, your task is to give covering fire for units (including Price and Soap) on the ground. Your primary – indeed only – method of doing this is using heavy ordinance or a massive Gatling-style gun to rout the enemy forces.

Throughout the level's short running time, you'll routinely (in all senses of the word) fire gigantic explosive rounds into fighting – or sometimes fleeing – enemy forces. Just like in reality, there's a pregnant pause after the launch of one of the heavier missiles, punctuated with the silent yet desperate running of those on the ground. Then, a puff of smoke. Job done.

And yet, despite the heavy metal at your disposal, and the outrageous power you can (and will) bring to bear on these foes, the operation itself has a frightening lack of ceremony to it. You are God, essentially, and what you are doing isn't wrong or even unjustified – it simply is.

Many different factors make it so. The aforementioned visuals are a key element of it: low-resolution, difficult to make out, and accurate to real life. A quick google will find you footage that is eerily similar.

But it's the dialogue that really sticks in the mind. Cold and deliberately dispassionate, it's also filled with joking asides between the fire control officer and the TV operator ("Clean up that signal", barks the chief, like someone about to miss his favourite show if it's not fixed). Select highlights include: "Nail those guys", "Woah", "Hot damn", "Good kill, good kill", "Oopsie-daisy", "I see a lot of little pieces down there", "Ka-boom", and, finally, my personal pick: "That's going to be one hell of a highlight reel".

These phrases are repeated often throughout the 10 minute or so running time, and each is delivered with either the boredom of a telephone operator taking instruction or the barely-disguised glee of a fratboy detailing his latest, greatest, fart. Even the name of the level is comical.

Many games use military jargon, and there will many be more to come. But few have managed to combine it with the other real-world elements to such an effect. We're all tango down'd and oscar mike'd out by now, so much so that every time we hear them we barely suppress a laugh. But here, these turns of phrase and euphemisms are exposed for what they really are.

As is the uncertain nature of warfare, even when you're controlling a multi-million dollar metal bird of prey that has more firepower and tracking systems than Robocop's older, harder brother. At one point in the mission, there's confusion in the plane as the crew try and ascertain exactly which part of the (very simple) road ahead they should be looking (shooting) at. One of them asks for clarification. "Which one's the curved road, Over? We're having a bit of trouble acquiring the village...how far up is it?" he asks. The response? "Ugh...hang on."

It's not exactly confidence-inspiring. But then again, neither is its real world equivalent. Whether Infinity Ward intended to replicate some of modern war's most excruciating air support blunders or not, misidentification of targets and directions has played a key part in actual disasters, despite all of the technology available to those controlling the operation.

These include a 1991 Gulf War friendly fire incident which saw an Apache helicopter commander open fire on his own side, due to confusion as to what he was firing at as well as ignoring orders and unwittingly drifting in the night wind. Watching the footage, the combination of arrogance, faith in technology and reductive expression that led to this disaster is replicated well in Death From Above.

Towards the end of Why We Fight, Eugene Jarecki's excellent documentary about the military-industrial complex, an interviewee who was a helicopter gunner in Vietnam gives his thoughts on his actions. He described the act as "shooting at dots on the ground. Like they're not like real human beings...they're objects."

We've been shooting at objects for years, of course. But not before Death From Above, and not really after (despite the raft of imitators), had shooting objects on screen been so realistic as shooting objects in reality. Ooh-rah.

Batman Arkham Knight Guide: Creature Of The Night Guide

Batman Arkham Knight Guide: Creature Of The Night Guide How to Reduce the Cost of Training Herblore in RuneScape Using Creature Creation, Livid Farm and Managing Miscellania

How to Reduce the Cost of Training Herblore in RuneScape Using Creature Creation, Livid Farm and Managing Miscellania Dragon Age Inquisition: Haven Side Quests Guide

Dragon Age Inquisition: Haven Side Quests Guide How to Reduce the Cost of Training Herblore in RuneScape Using Tasks, Distractions & Diversions and Cheap Potions

How to Reduce the Cost of Training Herblore in RuneScape Using Tasks, Distractions & Diversions and Cheap Potions Runescape Money Making

Runescape Money Making