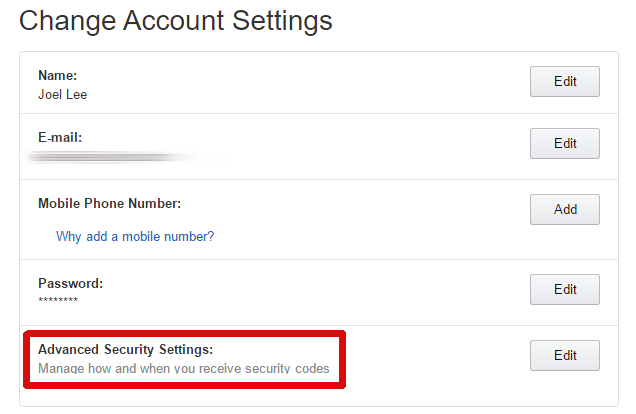

What is it that makes effective horror work? Mind you, when I say horror, I don’t mean jump scares or gratuitous amounts of virtual blood splashing across the screen. Horror for me means being thrilled—in a not-too-good way. Being scared, even. Being afraid of taking a peek around the corner out of fear what might await me there.

In the realm of gaming, there are quite few titles that successfully pull this off. While there are a lot of games that feature jump scares around every corner, only a small number of entries into any genre manage to elicit a feeling of genuine unease, and even fewer manage to truly, deeply scare.

In order to understand this relation, I first want to point out how effective horror does not work in games—how it is oftentimes undermined by certain game mechanics.

The big difference between non-interactive media and games’ approach to horror is, that the consumer (read: the person in front of the screen, not the person giving up money) of a book or movie is forced to witness gruesome things happening without the means of preventing them. In a game, the player is usually given any amount of tools to work against whatever the source of dread might be.

After some initial shock, even the most gruesomely hideous monster eventually becomes just another entry in a glorified shooting gallery.Interactivity in a large number of horror games boils down to action gameplay with the usual toolset—guns, knifes, sharpened (or blunt) sticks. With these tools, and in with the opportunity to proactively and aggressively defeat whatever horrors the game might throw at the player, tension filled situations arise for sure. However in the way that games usually work, those situations usually are designed so that the player can overcome them—maybe not easily, but aggressively and actively.

This undermines the scariness—the horror at hand. After some initial shock, even the most gruesomely hideous monster eventually becomes just another entry in a glorified shooting gallery. Worse yet, even the most hideously gruesome monstrosity will become familiar with time. The player has learned that their bark is usually worse than their bite, and their bite usually can be countered with a blast from the trusty, ubiquitous shotgun.

There are however some exceptions to this. One would be the infamous Pyramid Head creature from Silent Hill 2. When the player first encounters it, after having had a few glimpses of the monster in cutscenes and the game proper before, it quickly turns out that the rules from the rest of the game don’t apply to this particular creature. Any weapon at the players disposal is ineffective, and this first encounter cannot be won by attempting to overpower the Pyramid Head, but by evading its attacks, until the creature just walks away to disappear for a while.

Some time later in the game, the creature re-appears, hunting the protagonist down through a twisted maze. At this point in the game, the player is very much aware of his weapons being useless against this thing, which eventually adds to the absolute dread every other encounter with it evokes.

Another example of a prominent exception is the equally infamous Shalebridge Cradle level from the third Thief game. I needn’t go into any further details about the level, which Molly Carroll wrote about in her article yesterday. Kieron Gillen has also provided the ultimate rundown of that level.

Both of these examples are from games that apart from these encounters may be creepy, but not necessarily outright scary and horrifying, mostly due to the game mechanics or the thematic nature of the game.

Silent Hill 2 is a great game, a great narrative and a good horror game, but due to its main game mechanic being one of fighting rather than avoiding terrible creatures, it isn’t always quite as effective as with the Pyramid Head encounters, since the player can just blast his way through all the other horribly disfigured creatures the game features as opponents.

Thief is a series with a lot of mysteries and supernatural things going on, but it’s main mode of operations isn’t scary by most means—which makes the scary moments in the game even more powerful in contrast.

So from the negative provided above, it’s possible to derive a possible positive in terms of how horror works effectively in games. Basically, effective horror is an issue of player agency. However, the problem is that if the player has too little agency, in a horror game that aims at being effective by limiting the player’s options too drastically, it can quickly become frustrating instead of scary.

For a game to be truly scary, the player must not have the possibility to just go out and kill the source of fear with a shotgun blast.

Amnesia’s effectiveness stems from the game’s mechanics being aimed at making the player very vulnerable and not providing any method of fighting the horrors lurking around in the dark crevices the game offers for exploration.This is a scare tactic that has been proven effective by a number of games. One of the first was the Clocktower series, in which the player had to effectively evade any pursuer. A similar method was used in some parts of the (Forbidden) Siren series, most drastically so in the most recent entry, Siren: Blood Curse / New Translation, in which the player takes control of a little girl for some part of the game, which can only evade the mean spirited zombies. In both these cases, the limited player agency in combination with ‘stealth’ works exceptionally well for making the game experience absolutely horrifying.

The pinnacle of scary games though without a doubt is last year’s Amnesia - The Dark Descent, an independently funded title by Fritional Games using their own HPL Engine. Amnesia’s effectiveness stems from the game’s mechanics being aimed at making the player very vulnerable and not providing any method of fighting the horrors lurking around in the dark crevices the game offers for exploration. Also, the game plays very strongly with darkness, light and sanity. The game’s protagonist suffers from severe fear of the dark, which means if he stays in unlit areas for longer times, his sanity begins to slip, making him harder to control effectively. But the ghoulish monsters lusting for blood can see him when he stands in a lit area. Also, taking a glimpse of a monster takes a toll on sanity.

So whenever a monster comes around, the character has to hide in a dark corner, slowly going insane, staring a wall, observing the gruesome sounds of the horror lurking around. Horror in games can hardly work much more intense, much more effective than this.

The difference between Amnesia and a lot of other horror games is that Amnesia is not an action game with a lot of combat that’s dressed up as a horror title. The game's mechanics are geared toward horror alone. If more designers tried embracing this approach, we would see a lot more games that truly deserve to be called scary. So by making a game impressively scary, designers should start with the mechanics. The best story and environments and creepy sound work won’t help too much if your horror game is just horror flavored action.

(Ed: For more scares, read about the Best Horror Games on the PC of All Time.)