The website speaks, and something deep inside your mind responds. “9 Most Adjective Nouns…” Before you know it, your lizard brain has clicked. Aha! Now you are trapped in recursive clickbait, and this time about an incredibly boring subject: the 9 Most Important Numbers in Games. But because videogames are a computational phenomenon, numbers go deep into their history. At the lowest level of hardware, all computer games are numbers, and good mathematics remain an essential skill for programmers. So now that you’re here and we’ve got your ad revenue, why not click on? You might even learn something.

#9: £17,000

In 1823, the British government gave Charles Babbage a grant of £1,700 to build the world’s first computer.* By the time they pulled the plug on the project in 1842, they had given him over ten times that amount without receiving a working engine – making £17,000 the final cost of the first cancelled over-budget computer project in history. What I'm saying is that Charles Babbage’s famous Difference Engine was the Duke Nukem Forever of the 19th century. And just like the Duke, it was eventually built – by the London Science Museum in the 1990s, using only materials and techniques available at the time. It worked. That will be of little consolation to Babbage, whose scrappy work habits and eagerness to start designing a new and improved Analytical Engine lost the trust of his backers. “Hey, you know that thing you paid me to build? It’s not done yet, but I’ve thought of something that would make it obsolete!” Yeah.

*There is some disagreement about this; the first mechanical calculator was built in 1642, but Babbage’s would have been the first Turing-complete device.

#8: 9,999

‘999’ would work for this entry, as would ‘99’. The point is, how many games have left you gnawing your controller in frustration once you hit this perversely taunting resource cap? Whether it’s 99 lives in Super Mario Bros. or 9,999,990 points in Grand Theft Auto, older games tend to let you get ever-so-close to a good round number – and then stop you there.

In fact, this was not a matter of how many digits the hardware could store (hardware caps do exist, but they’re usually a power of two minus one, and always hidden behind the screen). Instead, it’s about visual space. In this modern age of HD TVs and four-by-four-digit resolutions, developers have ample screen to play with – but in more primitive times each pixel came at a premium. Only so many digits could be packed into the counter, and while each individual number could change, the number of digits never could. What was once a technological necessity is now an established convention, and gamers young and old are frustrated in the search for the perfect circular wholeness of zeroes.

Historical quirk? Maybe, but the incomplete stat counter seems to get somehow to the heart of computerized play. Isn’t a game always over once we have ticked every box and maxed out every counter? Conversely, a row of nines suggests that there will always be something missing, always something we cannot access – always a desire that will never be met. Good life lesson!

#7: 3d6 & d20

To determine thy stats, adventurer, roll 3d6 and apply in the order you rolled them…yes, the classic Dungeons and Dragons system has not only inspired dozens of computer RPGs but formed the mechanical backbone for more – starting with 1988’s Pool of Radiance and extending all the way through Baldur’s Gate, Planescape: Torment, and even Knights of the Old Republic.

At the turn of the millennium, Wizards of the Coast, who now own the D&D license, rolled out a new d20 system – centred around a now-infamous twenty-sided die – and opened it up to other RPG makers under something like a creative commons license. The company claimed: “one of the major factors which caused the collapse of the commercial tabletop RPG market from 1993 to 1996 was the proliferation of different, incompatible, core game systems.” The system has proliferated across tabletop and computer RPGs alike.

#6: $1.70

One point seventy dollars is the amount of money social games make per person in Who Killed Videogames – Tim Rogers’ majestic account of the social gaming industry circa 2011 and its “cruel mathematics”. As Rogers explains, this player is only “the fluffiest of math ghosts”, and doesn’t exist: “No one actually spends a dollar and seventy cents on a social game…it’s the average of a list of numbers that includes a few five-digit numbers and a sprawling ocean of zeroes.”

Rogers calls this player “the ghost in the middle”, and goes on: “This person, naturally, doesn’t exist in exact dimensions. In reality, he spends either one cent or nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine dollars and ninety-nine cents. Somewhere, in The Social Games Dimension, math is distorted, and the average of those two amounts is one dollar and seventy cents…”

The Man Who Spent One Dollar and Seventy Cents is a tribute not only to the enduring strength of the social gaming industry but to the importance and the blindness of metrics in game development. It’s probably not even the same number anymore. It doesn’t matter. There will always be more math ghosts.

#5: Two

Two: the number of the sequel. Like them or loathe them, they have always been around and always will be – but they have a special significance in today’s gaming landscape.

In games more than any other medium the sequel is a double-edged sword. Because they’re software products as well as artworks, playgrounds as well as narratives, they can be broken. Moreover, they’re broken in ways that can be fixed with a sequel which simply improves the system – something with no direct equivalent in literature or film. Hitman is one series which took four whole games to hit its stride; the first is crap, the second, middling, the third quite good and the fourth a masterpiece. Or look at MGS2, which uses your knowledge of the first game to fly off in a new direction.

But games, too, are becoming more expensive (see ‘$3.4m’), and sequels have always been a good bet. With Bobby Kotick’s comments that he only buys IPs he can exploit endlessly, and series like Modern Warfare and Assassin’s Creed proving tireless cash cows, a big fat two is a surefire way to get the bean-counters to sign off on your project.

#4: K = i*c

Not a number per se but a formula, k = i*c – otherwise known as K-Factor – is the equation used to measure virality in social market. Put simply, it expresses the rate at which your players are successfully inviting their friends to your game. But how does it work?

I could explain. I could say that it involves multiplying the number of invites sent by each customer to their friends by the rate of conversion (expressed as a fraction of 1) at which those invites are accepted. I could tell you that a k-factor of 1 means your player base is growing at a stable rate of , that under 1 means you’re declining, and that over 1 means you’ve gone viral. But telling you this would be to replicate the claims of a bunch of people who don’t actually seem to understand the numbers they’re using.

There’s a lot of different explanations of how K-factor works. Not all of them work together and not all of them make sense. Most of them DO raise questions they don’t answer, so if the entry on $1.70 is a picture of social gaming marketers as shadowy masterminds of a global addiction plot, consider this the corrective: sometimes, successful people have absolutely no idea what they’re doing at all.

#3: 30

The standard size of a rifle or machinegun clip in videogames, if not in real life, the ubiquity of the number 30 testifies to the slow ‘realification’ of even the most ludicrous shooting games. In the days of Doom it was enough to have a hundred bullets which somehow made their way to your superpowered space gun, but now our firefights – almost without exception – are punctuated by the pause, slap and click of a hasty reload.

It’s interesting to trace the spread of this paradigm. Duke Nukem 3D, the last of the great sprite shooters, was also one of the first to have reloads with certain weapons (like the pistol); the same year, Quake stuck to the old ways. In 1997 Goldeneye wowed N64 fans with now-amusing ‘realism’ while Quake 2 doubled down on bouncy fantasy gunplay. 1998 brought Rainbow Six, 1999, Medal of Honor, and though the anti-realist shooter saw a multiplayer flowering with Quake 3, Unreal Tournament, and Starsiege Tribes, Counter-Strike was already in the water. A few years into the millennium and clips were undisputedly king. Now, even Bulletstorm – a game attempting to hark back to the happy days of yore – includes the function. As Slavoj Zizek put it in his perverse tribute to Margaret Thatcher, “the true triumph is not the victory over the enemy; it occurs when the enemy itself starts to use your language, so that your ideas form the foundation of the entire field.”

In a sense, though, what we can really learn from the number 30 is that gaming’s commitment to ‘realism’ remains skin-deep. It’s a way of signifying realism on the level of player verbs without needing to simulate a realistic world. That’s fine – ‘realism’ isn’t merely good for its own sake – but the appearance of 30 across all kinds of ultimately very silly games should remind us that it can’t be achieved merely by accurate modeling of weapons. Then again, Wolfire’s Receiver is pretty cool.

#2: $3.4m

$3.4 million? That’s what failure looks like. Well, sort of: it’s the amount of money that the new Tomb Raider made in its first month while still failing to meet its publishers’ expectations. That’s right: Square Enix were banking on selling even more copies than the number required to count as the highest sales in the history of the entire series. According to gamesindustry.biz, it really needed to make $5 million just to break even.

This is the number that represents the dire state of the AAA games industry. When huge titles meet critical and commercial success but still don’t meet your hopes, your business model starts to look pretty dangerous. Crystal Dynamics head Daniel Gallagher did say he was “happy with the outcome”, but it didn’t manage to save his publisher from deep cuts and layoffs. As veteran journo Richard Cobbett has put it: “Everyone wants to have the next GTA or Assassin's Creed 3 or Call of Duty, but the simple fact is that most can't.” Sooner or later, numbers like these will catch up with the gaming industry. That makes it the second most important number in videogames, according to my frogmatic numerometer.

#1: 256

But without the number 256, I wouldn’t be typing this at all. This is because the number 256 is a foundational building block of computers, and without the pressure valve of computer games my parents probably would have killed me at age five when I made so much noise a man came round from nearby and punched my father in the face.

Because any piece of information on a computer ultimately exists as a set of charged or uncharged components (bits), they have to count in binary – that is to say in powers of two. But that means that, just as you can’t write ‘1,000’ in decimal notation without at least four digits, what you can express in binary is limited by the number of bits you’ve lined up. And because each bit has fewer ways to express itself than a decimal digit, you need rather more bits to get going: four to count to 15 (1111), five to count to 31 (1111) and ten to count to 1023 (1111…oh, never mind).

Hardware manufacturers needed to group bits together for convenience, and for no particular reason they settled on groups of eight called bytes (or octets). With a full byte you can count all the way up to 1111,1111 – or, in decimal, 255 – and since computers always count zero first, each byte has 256 possible states.

Even now, processors can only handle 32 or 64 bits of information at once (or more, through complicated juggling I don’t understand). But the memory banks they work with are measured in millions or billions of bytes, comprising a ludicrous number of possible states. I bet if you made a pile of all the states a modern computer can hold, they’d reach all the way to Pluto. That’s the glory of maths.

How to View & Send the New iOS 9.1 Emojis on Android

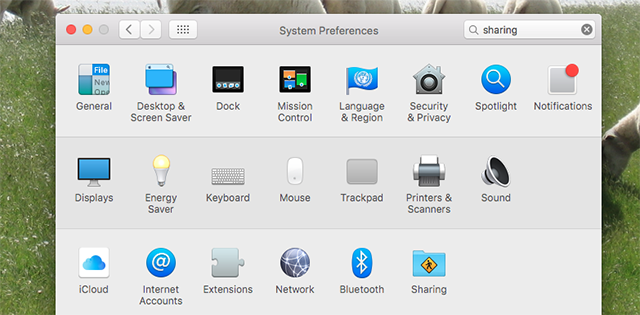

How to View & Send the New iOS 9.1 Emojis on Android How to Share Your Mac's Internet Connection Using OS X

How to Share Your Mac's Internet Connection Using OS X Battlefield 3 Beta Tips and Tricks

Battlefield 3 Beta Tips and Tricks Portal 2 trophies list for PS3

Portal 2 trophies list for PS3 6 Reasons Why You Cant Play Destiny Raids

6 Reasons Why You Cant Play Destiny Raids