Legend of Grimrock was the triumphant resurrection of a long-dead genre. Twenty years ago, first-person roleplaying games with real-time combat were the height of sophistication. I remember: I was there, playing them and having an amazing time. The question is whether this sequel can bring fresh creativity to grid-based dungeon crawling.

Instead of a dungeon, your team of four prisoners is shipwrecked on a mysterious island. You can run the default party, or build your own from an expanded range of character options. These include the disease-immune Ratling, and the Farmer, who improbably gains experience from eating instead of battle. I was frustrated by the original's long skill trees, which forced me to specialise before I understood the game, but there are now more skills with fewer levels, so I felt safe experimenting without fear of spoiling my character builds. It's enough flexibility to satisfy those who enjoy optimising statistics, but it's not necessary for success.

When ready, you're released into one of the new outdoor areas. The beaches and bogs, forests and foggy graveyards all look spectacularly atmospheric in the improved engine. But it's an illusion. You're still moving around a grid on a one-tap, one-square basis. The oddly geometric riverbanks give the game away: it's just a dungeon without a roof.

There's still plenty of underground action too, to please the purists. No longer limited to single storeys, the design kindles a wonderful desire to explore. With so many novel environments, it's easy to lose track as you wander down every path and staircase. Several times I'd be scouring a new area for clues, then stumble over some hidden dungeon. Unable to resist the lure of discovery I'd emerge hours later, clueless as to what I'd been doing in the first place.

To see it all, you'll need to get past the puzzles that often control access to new areas. The diabolical mix of logic, riddles and hidden objects that characterised the original remains intact. Sometimes the solution is a distant pressure plate or secret button, sometimes it's experimenting with diverse switches and levers. There's little handholding: just you, your brain and the uncaring pixels. Getting stuck made me feel anxious and alone. The payoff for cracking the answer was a fleeting moment of being the cleverest gamer in the world.

With so many novel environments, it's easy to lose track as you wander down every path and staircase.

That extra map space has been used to up the ante. Now, some puzzles demand you piece together clues and objects scavenged from the far corners of the island. Opening one stubborn door required me to untangle a cryptic riddle hidden in a library at the bottom of a distant dungeon. It's sometimes overwhelming: faced with some fresh conundrum, I was never certain if the answer was under my nose or hours further into the game. The problem is exacerbated by limited facilities for note-taking, buried in the automap.

If you do get stumped, you can always take a break with the new dungeon builder. Creating your own environments is time consuming, with lots of options to play with, but the simple interface makes it relatively easy. No doubt we'll soon see plenty of fan-made dungeons to download—many less vexing than their progenitor. It hardly bears imagining that some might be worse.

Some puzzles require real-time dexterity, such as the spike trap that requires precise timing to navigate. Combat is the bigger test of reflexes. You launch attacks by clicking, either on weapons or rune combinations for spells. Often you'll also need to quaff a potion or use a magic item in the melee. Monsters often seem to be one step tougher than your party, so even with the relatively sedate pace of the action, overcoming foes demands a skilled frenzy of coordinated clicks.

In the original, fights devolved into a slow-motion circle strafe of backing off and looping round, trying to land blows while avoiding pain. But many new monsters have new moves to thwart this trick. Some have ranged attacks, some assault all adjacent squares and others tumble sideways faster than you can run. This makes combat more tactical affair, where you have to use the scenery as a shield. It also encourages experimentation with the expanded palette of spells and missile weapons. The latter include primitive firearms that are almost as dangerous to the heroes as the monsters. One new class, the Alchemist, minimises this risk by reducing the chance of malfunctions.

Grimrock's greatest strength has always been the seamless stitching of diverse elements. By adding new angles in exploration and tactics, this sequel brilliantly expands the synthesis of puzzles and twitch action that made the original so memorable. Existing fans will love it. But by continuing the unwavering dedication to difficulty, it's unlikely to win new converts to this neglected genre.

Fallout 4 Guide: Where To Find All The Companions

Fallout 4 Guide: Where To Find All The Companions Destiny Beta: Hidden Gold Loot Chests Locations

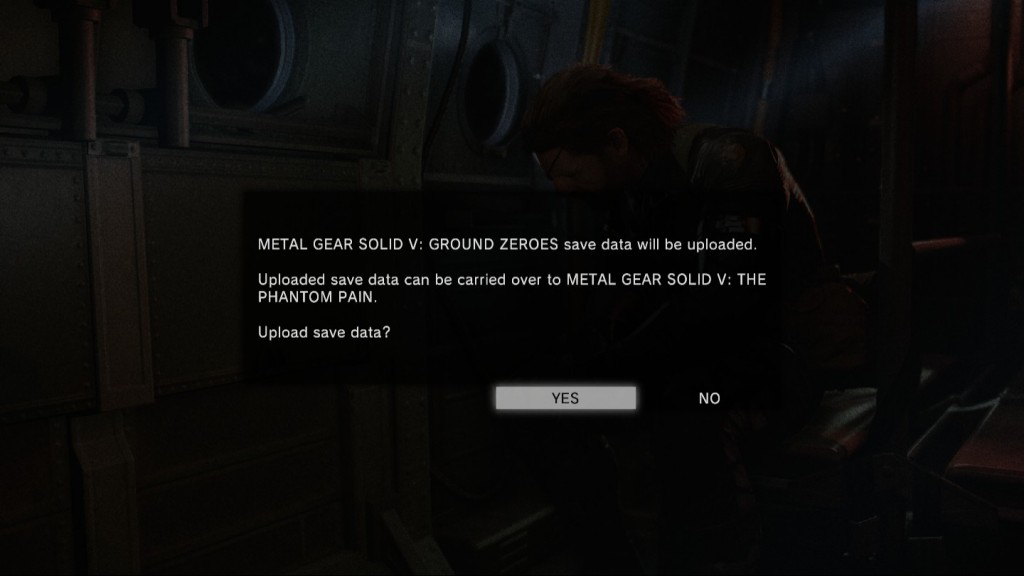

Destiny Beta: Hidden Gold Loot Chests Locations Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain Guide: Here's What You Can Unlock With Ground Zeroes Save Data

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain Guide: Here's What You Can Unlock With Ground Zeroes Save Data Watch Dogs Unlocking ctOS Towers Walkthrough

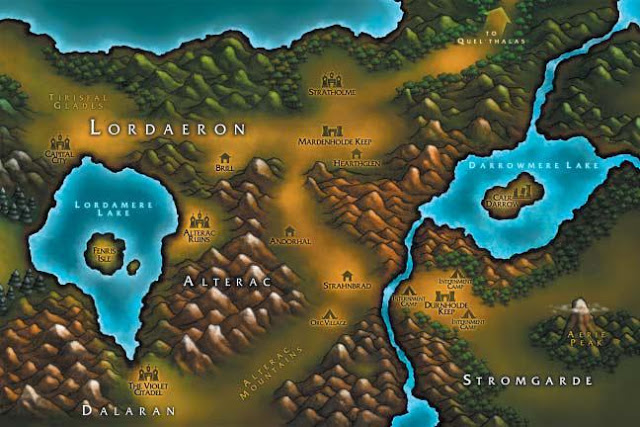

Watch Dogs Unlocking ctOS Towers Walkthrough World of Warcraft - Enter into the Hidden Zone

World of Warcraft - Enter into the Hidden Zone