The first time I rounded a corner in Sunset I just about fell out of my chair, startled by my own reflection as I came nose-to-nose with a glass door and a low-res woman with dead eyes, barely blinking, peering at nothing. It was creepy, but I got over that. What I couldn’t get past was the feeling that I wasn’t the real Angela Burnes. Sunset’s protagonist comes in two forms: one is a character in the story, and the other is a reflection of the player and game designer, a distortion. The real Angela, I think, is the one who exists without me. When I took control, I felt like a fraud.

Angela is an young African American engineering graduate and activist who becomes stuck in a fictional South American city during a US-backed military coup. She makes ends meet working as a housekeeper for wealthy art collector and bureaucrat Gabriel Ortega, whom she never meets in person. Sunset explores their relationship, how they relate to each other and the unrest outside, and how that divides and connects them. Once a week, I assume Angela’s body and wander Ortega’s penthouse completing chores while he’s out—clicking on things that need doing—and poking through his belongings. I can also reply to his notes, and most things I do can be done ‘warmly’ or ‘coldly’. I can arrange his shoes playfully or neatly. I can help myself to a drink while cleaning up, or just put away the glasses. I can express my presence, leave kind and flirtatious replies to his notes, or be invisible to him.

Sunset isn’t really about investigating like in Gone Home, where everything has already happened and you’re piecing together the past from what’s left behind. It’s more like pausing an in-progress play and messing with the set dressings. I deduced some things from Gabriel’s possessions, but anything I missed was filled in by Angela’s voiceovers at the beginning of each day. The unnatural mouthfuls felt over-rehearsed, like she woke up and pre-planned her thoughts about “people organized by hierarchy, aimed at each other with purpose, instead of breathing and flowing through each other, like a city’s supposed to feel.”

Being a bit overwritten is fine, because the plot is interesting—it follows the rise of an oppressive new government and the rebels opposing it—but Angela’s thoughts seemed to come from a different person than the one I was playing as. When her brother became involved in the revolution, for instance, she deduced that Gabriel was angry about his actions, and in turn she was furious at him and his privilege. And yet I walked around leaving kind notes and gently warming his austere penthouse. I didn’t understand why she would like the man at all, or show him any affection, but I wanted to see if my warmness changed anything. It doesn’t seem to, and you won’t find Telltale-like moral conundrums or branching paths.

Sunset itself also seemed to push me toward the flirtatious Angela. The blue, cold options were dull, while the warm options were creative and smart—it was hard to make Angela humorless, because she didn’t seem that way, but the warm options didn’t fit either: she’d never met this man, she resented him, so why did she seem so fond of him so quickly?

I felt a little uncomfortable in Angela’s shoes, like I was acting against her will to satisfy my own hopes for the story. I don’t think that was the intended theme—my relationship with Angela and the game—but I still enjoyed the plot and what feelings I did share with her. I felt lonely when Gabriel left town, even though the apartment was empty whenever I arrived anyway. I felt comforted when I put out a still-smouldering cigarette and tidied other evidence of life. It felt good to be kind to him in his depression—whether or not that’s what Angela would do—as I tried to drive the pair’s relationship toward something caring. The two are divided by wealth, power, and ideology, and discovering their values, or how they approached the same values differently, was fascinating enough that I wanted to see it through, even when it started to drag.

That happens about halfway through, when the plot slows and then gently rolls—with a couple of spikes—into a foreseeable conclusion. At that point, some of the days really did start to feel like chores, especially when I got vague tasks like ‘clear the area in front of the windows.’ The apartment is pretty much made of windows, so that’s just a mean joke, making me shuffle around the place looking for a hotspot to click on. And even though I rarely chose the ‘cold’ options, getting the interface to show me them was finicky, adding to the sense that I wasn’t ‘supposed’ to choose them.

At one point I just sat down and listened to music, enjoying the pink and orange light in the approach to dusk.

I liked being in the apartment, though, even after I was bored of checking off Ortega’s to-do lists. Sunset nails the 70s design with keenly observed light fixtures, furniture, and architecture, as well as fantastic playable records with properly space age stereo equipment. At one point I just sat down and listened to music, enjoying the pink and orange light in the approach to dusk. Angela’s growing relationship with the space is the most interesting relationship in Sunset. As it progresses, the disconnect between her internal dialogue and affection starts to resolve, and I can see how she’s become attached to Gabriel's quirks and passions.

Given that a central theme is the juxtaposition Gabriel’s values with the burning city he holds them above, the city itself is a bit underdeveloped. The buildings outside look like cardboard models, and don’t fit in. I encountered a few other off-putting visual flaws: an untextured object, glassware that looked like it melted spacetime, and overzealous orange lights that caused the staircase to turn radioactive. I also had a problem with the mouse disappearing (turning off my second monitor fixed it), but Sunset mostly ran just fine for me, and its visual flaws were rare, if acutely noticeable among the otherwise pristine light and lines.

Sunset delivers an interesting plot and interesting characters, but I often felt like an invader, like I should have been reading Angela’s memoirs rather than adding notes. But it tries to tell a story in a way I haven’t experienced before, and I’m happy to have played it, and to be thinking about how young interactive storytelling is and how it might evolve. I also appreciate that Sunset’s creators have put writing about things like civil rights, class structure, and intimacy into my game library—sat among a mostly homogenous set of themes, Angela represents a happily broadening spectrum of characters and ideas in PC gaming.

Silence: The Whispered World 2 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game .

Silence: The Whispered World 2 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game . 4 Tips for Doing Real Research on Android

4 Tips for Doing Real Research on Android Mario, Hyrule, Splatoon: Here's How Nintendo Won E3 2014

Mario, Hyrule, Splatoon: Here's How Nintendo Won E3 2014 How to Manage Windows Update in Windows 10

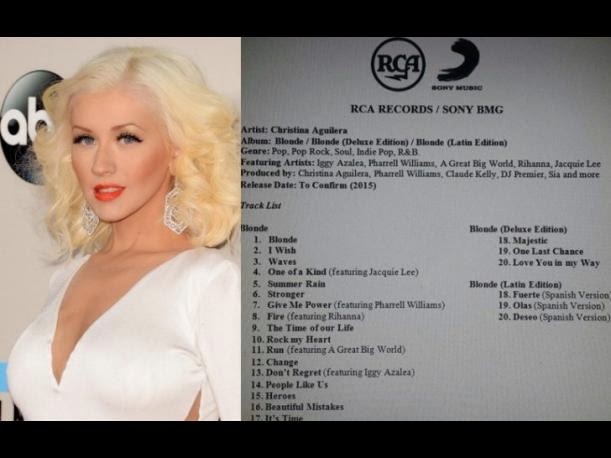

How to Manage Windows Update in Windows 10 Details for Christina Aguilera’s Upcoming Album Potentially Leaked

Details for Christina Aguilera’s Upcoming Album Potentially Leaked