SOMA is, essentially, a deadly game of hide and seek with a parade of increasingly bizarre mechanised monsters. You have to make it from one end of underwater facility PATHOS-II to the other without being spotted. Along the way you learn about the base, the sinister experiments going on there, and what happened to its mysteriously absent employees. It’s a pretty basic horror game at its core, but elevated by a compelling sci-fi story and a hauntingly evocative setting.

The game is viewed from the first-person, and you interact with the world in a brilliantly physical way. Click on a door to grab it, then push with the mouse to shove it open. Click to take hold of a switch, then pull back to yank it down. Anyone who played Amnesia will be familiar with this. Everything you touch, push, pull, and pick up feels heavy, tangible. There are no weapons, gadgets, or tools to help you, and you can’t fight back. All you can do is run and hide. It’s a resolutely minimalist game, but with lavish production values that make it feel much richer than it really is.

I can’t say who you are, or why PATHOS-II is in such a mess, because both represent the backbone of the plot. It’s a game of slow revelation. You, like the protagonist, are completely clueless at the beginning. You don’t know why you’re there, why it’s crawling with murderous machines, or where everyone is. But the truth is drip-fed over time, until the reality of your situation hits you like a brick. It’s a wonderfully told, and written, story. It compels you to keep pushing on through the darkness, with shock moments that make you rethink everything preceding them.

Amateurish voice acting is the only sore point. The main character, Simon, never sounds particularly bothered by anything happening to him, including a mid-game twist that would send anyone into shock. Honestly, I don’t like or care about him that much, which diminishes the fear factor. The supporting cast are a mixed bag, but are largely just as unconvincing. However, it’s testament to the quality of the world-building and writing that, although sometimes distracting, the am-dram acting is never enough to make you stop believing in what’s happening.

For me, the highlight of the game is PATHOS-II itself. The best storytelling is found in the environments, not the characters. Located at the bottom of the ocean, it’s Rapture meets the Nostromo. Its claustrophobic, labyrinthine metal corridors are straight out of the 1970s handbook of hard sci-fi set design, and it’s absolutely drenched in atmosphere. Flickering lights, burst pipes, leaky bulkheads, and a strange, black, alien goo seeping through cracks in the ceilings is a constant reminder that this place is seriously broken. The story takes you on a tour of different parts of the base, and they all have distinct personalities and stories to tell.

The lighting is fantastic, making you forever wary of what horrors lurk in shadowy corners. You see peculiar, almost organic machinery dotted with glowing lights, like something out of an HR Giger drawing, that seems to be eating the world around you. Visually, it’s a masterpiece, and every room tells a story: about the people who lived there, about what went wrong, about the outside world, or about yourself. Your character has the ability to touch certain things, including corpses and robots, and hear fragmented memories that tell tales about the base and its inhabitants before its collapse. It’s a setting flooded with hand-crafted detail.

While there are plenty of slow moments where you explore the base and learn about its purpose, it’s when the monsters arrive that SOMA enters more familiar territory. Its cast of robotic stalkers is varied, but their AI is rudimentary. Compared to the dynamic, unpredictable predator in Alien: Isolation, these guys just seem to pace back and forth, waiting for you to mess up and stumble into their field of vision. You don’t feel you’re being hunted by an unknowable evil: more like you’re trying to sneak past a security guard—albeit one made of wires and body parts.

They’re scary at first. You only ever catch glimpses of them in the shadows, which makes them more terrifying. Your mind fills in the blanks, which is always more effective in a horror game than just showing you something. The screen glitches and distorts as they approach, which sets your heart racing. They make horrifying sounds: screeching, rasping, and ranting about ‘black blood’ in garbled machine-voices. My favourite, who I’ve nicknamed Disco Man, has a head made of blinking lights that make the screen distort crazily if you look directly at it. This adds an interesting dynamic to sneaking around it in the cramped confines of a shipwreck, as you can never fully look at it to gauge its movement.

But the monsters’ initial impact never lasts. When they attack, you lose a ‘life’ and are sent back in time to just before they spotted you, giving you a chance to correct your mistake. The more this happens, the glitchier the screen gets, and you start limping. Get caught too many times and it’s game over and back to the last checkpoint—which are, to be fair, generous. In some of the trickier sections, when you inevitably die repeatedly, you’re no longer scared of your pursuer: just frustrated by it. Like I said earlier, it’s no more complicated than hide and seek. I ended up dreading the arrival of a monster, not because it was scary, but because it meant more trial-and-error stealth—and less time poking around at my own pace in those wonderful environments.

Occasionally you leave the confines of the base and wander the sea floor. These large, open areas are a nice change of pace from the narrow, metal corridors, and feature some of the game's prettiest visuals. Some of these sections see you dodging the roving spotlights of killer submarine-bots, but sometimes they offer (ironically enough) some breathing space. I spent a good while just wandering around watching shoals of fish and sea turtles swim past, putting off venturing into the next dark, dingy corner of the base. A level set on a sunken, barnacle-covered ship also offers some variety, and its twisting, cramped tunnels are genuinely nerve-racking.

It’s a curious combination, really: rote hide-and-seek horror, tied to a game with an intelligent, thoughtful story that reaches beyond the bounds of its own narrative. In this universe, people have found a way to make digital copies of themselves—their memories, personalities, flaws—and transfer them into machines. SOMA asks questions about the nature of humanity. It has things to say about free will, individuality, and morality. It makes you think—which in turn makes the bits where you’re being chased around in the dark by a mechanical monster all the more jarring.

SOMA has big, interesting ideas when it comes to story and themes, but this ambition and imagination doesn’t carry over into its game design. But, monster encounters aside, this stricken underwater base is one of the most fascinating, atmospheric spaces I’ve ever explored in a game. There’s all manner of horrific imagery down in those murky depths to be uncovered, and the story is unsettling. In this sense, it’s a great horror game. It affects you psychologically and emotionally—often in a subtle, understated way. But all this does is highlight how ineffectual its more familiar attempts to scare are. Ultimately, it’s what’s inside your head that scares you in SOMA, not what’s in front of you.

Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze Review: A Retro Return

Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze Review: A Retro Return Warhammer: End Times - Vermintide Tomes and Grimoires Locations Guide

Warhammer: End Times - Vermintide Tomes and Grimoires Locations Guide LA Noire: Reefer Madness DLC Walkthrough

LA Noire: Reefer Madness DLC Walkthrough Xenoblade Chronicles 3D Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game .

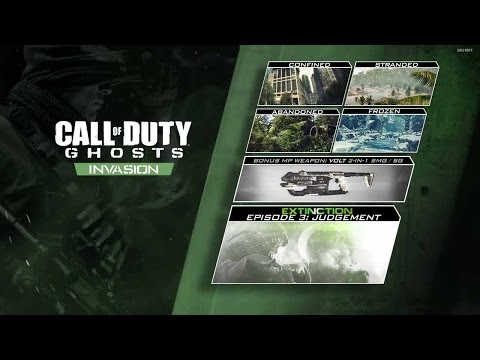

Xenoblade Chronicles 3D Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game . Call of Duty Ghost: Invasion DLC Achievements - Trophies List

Call of Duty Ghost: Invasion DLC Achievements - Trophies List