The Westport Independent is a game about censorship in a repressive society. You have 12 weeks before the enactment of a Public Culture Bill which will dramatically curtail your journalistic freedom. Do you scuff the polished jackboot of fascism and report the truth? Or do you protect your writers and stick to smouldering celeb gossip?

As editor, you can choose to support the government or encourage rebellion, and you’re in control of which stories get published and how they read. You can switch between different headlines, altering the intonation of each story. Don’t like that line about a study being government funded? Chop it out. The same article can be about a burglar being apprehended, or a homeless man being assaulted. These choices are determined by your moral compass (and how comfortable you are with your staff getting a compulsory manicure from the secret police).

You assign each piece to one of your four writers, who will reject or embrace a story depending on the angle. Some are loyal to the government, others openly in favour of rebellion. Report negatively and the government will view you with suspicion. Things such as mocking the president, questioning policy or drawing attention to deflation will put your writers on the naughty list. Do it too often and they might get arrested. A scandalous display of state repression, but also dashed inconvenient. It’s far harder to fill pages with fewer staff.

Eventually, you get to choose the layout of each issue, ordering pages by importance. This is crucial, because certain stories flourish in particular areas. The rich want to read about industry, celebrity and quail’s eggs, whereas the poor are more interested in crime and society (“Gritty news for gritty sailors”, although I don’t know precisely how sailors could get gritty). You can also alter distribution, and promote your paper in areas best suited to its content. There’s something gratifying about an expertly-pitched paper selling like gangbusters.

Predictably, my first attempt saw me ease into a tepid bath of cowardice. I avoided anything controversial, and stuck to stories about how jim-dandy the president was. It felt safe and sordid, but at least my writers weren’t murdered. By contrast, I went full rebel on my second playthrough. I blew the whistle on expensive presidential statues, and bleated about surging unemployment. My rebellious stance forced one writer to resign. Another ‘disappeared’. I timed my truthbombs horribly, and The Westport Independent closed with just one week to go.

This crisply defines how different approaches lead to different outcomes, but it reveals some flaws. The game rarely lets you report issues from oblique angles. You’re either openly in favour of the government or firmly against them. It’s zesty lesson in the power of spin, but it makes for an unfulfilling experience. As the government became more suspicious of me, I saved the paper by saying nice things about them, like a sickly boy caught making fun of the school bully. ‘No, Crusher, I definitely didn’t say you looked like a builder’s elbow!’

The bigger problem is with the characters. Everything you do hinges on whether or not you care about them. Threats to Frank’s safety mean nothing if you can’t remember which one Frank is. Some effort has been made to give characters a backstory. You learn about their home lives. Short cutscenes add personality by showing conversations in the canteen, and, unlike PC Gamer, they talk about politics and dating rather than which BioWare companion has the nicest hands. (It’s Solas, but the way—soft and supple like nugskin.) Sadly, like most editors, I rarely saw my writers as human beings. Their traits feel one-dimensional, and the cutscenes left me cold. The endings meant less because of this, and it dampened any sense of threat.

Your effect on society is a more satisfying metric. As somebody clever probably once said, the middle classes are the biggest cause of revolution, as well as the biggest obstacle to it. Trying to convert them made The Westport Independent more interesting. My paper became a martini of crime news and tawdry gossip, garnished with a cocktail olive of revolutionary discontent. I felt like I’d made a difference when the rioting finally touched the poshest areas, laughing as the artisan eggcup shops got vandalised. For me, this is where the game actually succeeds. Tempering reports and watching sales grow mattered more to me than how happy my staff were.

Sadly, it’s not enough. A single game takes around 40 minutes, and even though it’s designed to be played repeatedly, it feels laborious. You don’t start making important decisions until week three, and it lacks the immediacy of The Republia Times, which it no doubt took inspiration from. Comparisons to Papers, Please are equally damaging, because this lacks the black comedy or emotive twists. A game about censorship and the powerful reach of the press should feel more relevant than ever, but instead, The Westport Independent is quietly underwhelming.

THE VERDICT

Fallout 4: Hypothesis walkthrough

Fallout 4: Hypothesis walkthrough Destiny: The Taken King Guide - Where to find Taken Champions in The Taken War: Earth

Destiny: The Taken King Guide - Where to find Taken Champions in The Taken War: Earth Press X To Eat Flesh: 10 Examples of Cannibalism in Games

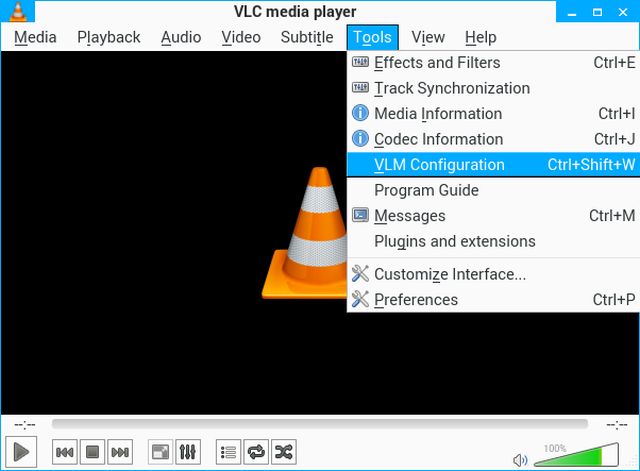

Press X To Eat Flesh: 10 Examples of Cannibalism in Games How to Create a Linux VLC Streaming Media Server for Your Home

How to Create a Linux VLC Streaming Media Server for Your Home In Defence Of Spelunky

In Defence Of Spelunky