It won’t call you names, but Dante’s Inferno will offend. Whether intentional on Visceral Games’ part or not – and in truth it’ll be a combination of the two – you’ll not enjoy every minute in Lucifer’s lair. The abhorrence begins with Limbo, the lair of unbaptized babies. When the first infant emerged crying from the hollowed-out womb of a female effigy (which is lying underneath the gaze of a fiery devil) we questioned whether we wanted to keep playing. As it waddled forward on wobbly legs our only option was to take a scythe to it. It’s easily the most disturbing moment we’ve ever witnessed on a console and one that’ll understandably upset a lot of people.

Dante’s also offends with its numbing repetition. Nothing epitomises Hell quite like the invisible barrier. The laziest of all gaming mechanics, it’s capable of marring almost any experience when used without limitations. Not that the opacity matters. Flame barriers, bone barriers, magic barriers: visible or not, ultimately they’re all as bad as each other.

Dante’s Inferno’s crammed with them. Step onto a circular platform or enter a long hallway and you just know you’re about to be attacked. Obstacles are strung across the one exit (Dante’s is as linear as a rope), freaks are pushed through the floor and you’ll be forced to clear house before moving along to the next battle. Occasionally Visceral throws in the odd brainteaser – never more than a basic lever puzzle – but for the most part Dante’s Inferno’s predictability is unmatched.

Then there’s Dante himself: a vile protagonist of astonishing proportions. Dante is fighting through Hell to save his murdered lover Beatrice and return her to Heaven. He’s so foul, though, that his overarching tale of redemption is ineffectual blubber. The man is unquestionably deserving of his trip through Hell, and while we’re supposed to root for his success and Beatrice’s salvation it becomes increasingly difficult to enjoy the skin you’re forced to wear.

The fourth, and perhaps the worst offence of all, becomes apparent only towards the end: the missed opportunities. Having set its marker with the truly horrendous unbaptised baby scene, Visceral Games bottles it. There are still nasty visions later on, but nothing that comes close to the first hour. The Woods of Suicide – a level deep down in Violence – could have been the most creative of all the areas. We predicted rows of hanged people and sobbing souls forever forced to slice their wrists like Sisyphus was forced to roll his rock (yes, this is how your brain works when playing this game). Indeed, your guide Virgil warns you not to enter because it’s too much to handle.

Inside though it’s little more than a few gnarled and admittedly quite peeved faces impressed upon the trees. Your first steps into the eternally agonising portals of Hell, massively disappointing gates aside, are memorable for the endless falling bodies and for tortured spirit after tortured spirit clawing at Dante from within the walls. A few hours into the adventure, however, the formula is never re-stirred.

The journey through the underworld is a whistlestop tour of all the epic poem’s major sights with plenty of dull filler in between. You’re whisked through the nine circles at such a pace that the major areas of Hell act as little more than footnotes punctuating lengthy nothingness. For every boss fight there are a dozen identical rope-swings and cliffs to rappel down. The sensation that you’re not exploring Hell so much as its maintenance tunnels is inescapable. This problem is sometimes compounded by a dodgy camera resulting in unwanted dunks in molten gold soup.

Best Minecraft Xbox One Seeds

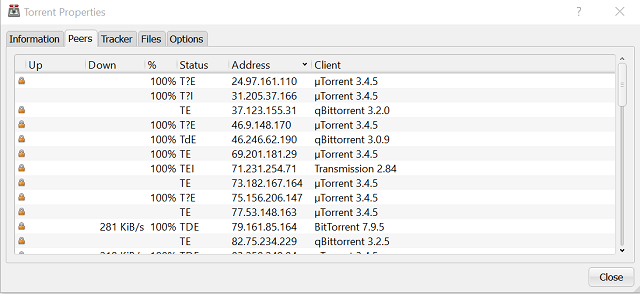

Best Minecraft Xbox One Seeds This One Vulnerability Might Leak Your IP When Using A VPN

This One Vulnerability Might Leak Your IP When Using A VPN MGS 5 The Phantom Pain unlock Cyborg Ninja costume of Gray Fox

MGS 5 The Phantom Pain unlock Cyborg Ninja costume of Gray Fox 8 Amazing Things You Can Do With an iPhone

8 Amazing Things You Can Do With an iPhone Kingdoms of Amalur: The Legend of Dead Kel DLC Walkthrough

Kingdoms of Amalur: The Legend of Dead Kel DLC Walkthrough