Many of us are wary of the data Facebook keeps about us. We may volunteer that information, but the extent to which the social network collects it might surprise you – as might what further details can be gleaned or inferred from what we surrender.

Let Digital Shadow loose on your profile and discover that a sophisticated programme can work out a fair approximation of passwords, even!

But the war against the global giant in re-establishing privacy is slowly being won – in Europe, at least. Because Facebook has been given 48 hours to stop tracking non-users in Belgium…

You read that correctly. Facebook tracks non-users.

It doesn’t matter whether you’ve been absorbed in the social phenomenon or resisted it. If you use the Internet – and because you’re reading this, you do – Facebook can track you.

They do this by creating shadow profiles. It’s a rough estimation of you, based on the sites you visit that are either Facebook.com domains (fan collectives, pages promoting companies or political parties, and profiles with sloppy privacy settings) or have a social plug-in that allows readers to “Like” pages. The latter is used on more than 13 million websites, and reads tracking cookies and feeds that back to the company.

The Belgium Privacy Protection Commission (CPVP/CBPL) reckons Facebook “tramples” on European privacy laws; Facebook insists that because their European headquarters is in Dublin, they’re only subject to Irish law. The Commission warns:

“[Tracking people through social plug-ins] does not only impact Facebook users but also virtually every Internet user in Belgium and Europe.”

As of 10th November, a Belgium court has now given Facebook 48 hours to stop tracking non-users who nonetheless visit the site – or else potentially face a fine of up to €250,000 ($267,725) a day.

Why? The court insists Facebook needs consent of these visitors to obtain any personal data. A spokesperson for the social network said:

“We’ve used the Datr cookie for more than five years to keep Facebook secure for 1.5 billion people around the world… We will appeal this decision and are working to minimise any disruption to people’s access to Facebook in Belgium.”

The cookie, according to chief security officer Alex Stamos, is used primarily to combat the creation of fake and spam accounts, and lower the risk of fraudulent activity:

“For example, if the datr cookie demonstrates that a browser has been visiting hundreds of sites in the past five minutes, that’s a pretty good indication that we are dealing with a computer-controlled device (a bot). On the flip side, consistent use over several days usually indicates that a browser is legitimate and should be able to access Facebook normally. While we use this aggregated, statistical information about browsers for security, we thoroughly delete logs generated by the datr cookie after 10 days.”

In fairness to Facebook, the CPVP/CBPL was forced to remove the accusation that data generated by the cookie then created targeted advertisements (which is one reason cookies are typically used for). Stamos further says:

“We do not set the datr cookie when someone simply loads a page with a like button.”

But back in 2011, that’s what the Wall Street Journal said the company’s cookies do. It remains a controversial cookie – because essentially, they’re interpreting either ignorance or inactivity as consent.

Many don’t realise that you’re tracked even if you don’t have an account. The vast majority, even if they do know, do nothing about it. Nik Cubrilovic, developer and former security consultant, says:

“Facebook can’t help but to track, since they are being sent the cookie by the browser on subsequent requests. They read the cookie, which means that they know it is the same visitor… [I]t is not a big leap to make to conclude that Facebook are tracking users and analyzing that data [for the purposes of advertising].”

Austrian activist, Max Schrems founded Europe v Facebook, an organization wrestling for your right to privacy on social media, and attempted to sue Facebook over privacy rights.

However, in July, a Vienna District Court dismissed the case, with Judge Margot Slunsky-Jost claiming Schrems was using the press generated by the class-action for a book he’s writing on data protection – and to further his profile as a privacy campaigner. Max told the Irish Times:

“I am not happy with the ruling but will go to a higher court. The court is simply passing the hot potato on.”

You can follow the Europe v Facebook movement on Twitter, and share their crusade on, uhm, Facebook.

Ahem.

How Facebook responds to the Belgian Court’s proposed fine unless they stop tracking non-users is likely to affect Schrems’ case… and that of the Article 29 Working Party, an independent regulator which also asserts that consent needs to be given for Facebook to collect cookie data.

This might not go through: Facebook is appealing against this decision. If it does, the fine of €250,000 per day would go to the Belgium Privacy Protection Commission.

Either way, the press generated by the case will make more people aware of potential privacy infringements. Obviously those directly affected would be anyone who lives in Belgium, but the implications could be more widespread.

Facebook would have to justify a decision to not track non-users in that country but continue to do so internationally – especially those in Europe. That sounds like a near-impossible task, but Stamos has already posted an argument for keeping the datr cookie en masse:

“In practice, that means we would have to treat any visit to our service from Belgium as an untrusted login and deploy a range of other verification methods for people to prove that they are the legitimate owners of their accounts. It would also make Belgian devices more attractive to spammers and others who traffic in compromised accounts on underground forums.”

People rightly worry about security, probably more so than their own privacy (which is why legislation like the Snooper’s Charter is being proposed), so it’s certainly persuasive rhetoric.

You can delete cookies, of course, and opt-out of personalised ads which publicize your likes. Alternatively, you could turn to a non-tracking browser extension. In fact, there’s plenty you can do in just an hour to regain your online privacy.

Nonetheless, we look forward to seeing how this case plays out.

Are you concerned about Facebook’s use of cookies? Or is it for the greater good? What other tips do you have for keeping personal data private?

Image Credits: Belgium by Mike Hammerton; cookie monster by Michelle O’Connell; and facebook website screens by Spencer E Holtaway.

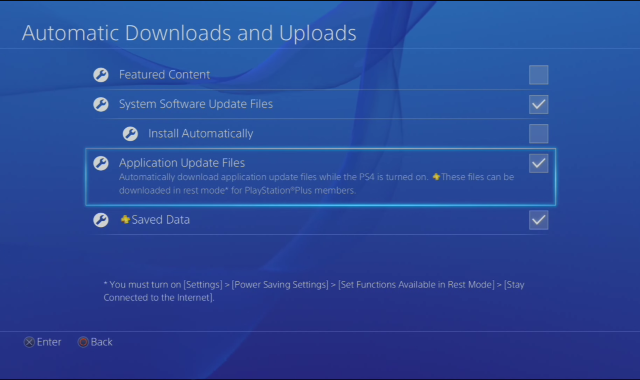

How to Make Your PS4 Update Automatically Every Time

How to Make Your PS4 Update Automatically Every Time Windows 10 Can Auto-Remove Software Against Your Will

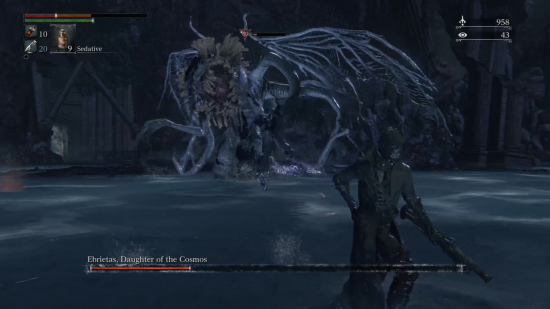

Windows 10 Can Auto-Remove Software Against Your Will Bloodborne Boss Guide: How to Beat Ebrietas, Daughter of the Cosmos

Bloodborne Boss Guide: How to Beat Ebrietas, Daughter of the Cosmos The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt - Gwent Card Locations

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt - Gwent Card Locations Xur Location And Exotic Items In Destiny For June 5-7th

Xur Location And Exotic Items In Destiny For June 5-7th