Malcolm Gladwell gave us the 10,000-Hour Rule. It turns out that rule is wrong. Here’s why, and how you can beat it.

In 2008, Malcolm Gladwell published his New York Times bestseller, Outliers. It’s within this book — based largely on the research of Anders Ericsson — that Gladwell frequently talks about the 10,000-Hour rule, citing it as “the magic number of greatness.”

The book looks at a number of “outliers”, people who are extraordinarily proficient in certain subjects or skills. It then tries to break down what helped them to become outliers.

According to Gladwell, one common factor among these carefully selected individuals was the amount of time they practiced within their area of study. It appeared that only by reaching 10,000 hours (that’s about 90 minutes per day for 20 years) of practice could one become an outlier. To use another of Gladwell’s popular terms, 10,000 hours is the “Tipping-Point” of greatness. You can see him explaining this here:

In the years following the book’s publication, this 10,000-Hour Rule has become a platitude for life-long learners, lifestyle designers, and self-improvement bloggers. This is despite increasing evidence showing that the 10,000-Hour Rule is grossly inaccurate.

This inaccuracy is good news for any of us looking to become even above average in a skill. Gladwell’s rule promised us a massive undertaking when tackling a new area of study.

Instead, it could be a lot easier to attain proficiency.

Anders Ericsson is a Professor of Psychology at Florida State University. It’s on the back of his research on Deliberate Practice that Gladwell constructed his book, and his 10,000-Hour Rule. Some people have misattributed this rule to Ericsson himself, which he sought to correct due to its misrepresentation of his actual findings.

Ericsson describes what could only be Gladwell’s work as:

“[A] popularized but simplistic view of our work, which suggests that anyone who has accumulated sufficient number of hours of practice in a given domain will automatically become an expert and a champion.”

Ericsson went on record clarifying that this is not what his research showed. Within that study, there was no magic number for greatness. 10,000 hours was not actually a number of hours reached, but an average of the time elites spent practicing. Some practiced for much less than 10,000 hours. Others for over 25,000 hours.

Additionally, Gladwell failed to adequately distinguish between the quantity of hours spent practicing, and the quality of that practice. This misses a huge portion of Ericsson’s findings, and is the reason why Tim Ferriss scoffs at Gladwell’s 10,000 hour rule in this video.

On this line, another of Ericsson’s studies showed skills (in this case long term working memory) which could be mastered in “a minute fraction of the 10,000 hours estimated to be necessary to attain high levels of expert performance”, using very specific, deliberate methods of practice.

The takeaway here is that practice may be important, but it’s not the whole story.

One study in Intelligence journal attributed practice to only “about one-third of the reliable variance in performance in chess and music”. The largest meta-analysis in the field found that practice may be responsible for as little as 12% of mastery.

That means there’s much more to mastering a skill than just months, even years, of practice. Genetics may play some role, but science is also giving us glimpses into what else we can do to learn more efficiently.

In recent years there has been a flurry of interest in skill acquisition, and particularly rapid skill acquisition. Tim Ferriss penned The Four-Hour Chef — a 672-page behemoth — tackling this very subject.

Throughout his book Ferriss introduced millions of readers to the idea of meta-learning. That is, the learning about learning. Once we understand how our brain and body learns, we can create a far more efficient learning regimen. In fact, Ferriss, during a SXSWi presentation claimed:

This may or may not be an exaggeration, but what Ferriss is emphasizing here is the quality of practice over the quantity. But even if the real figure is two-years, not six-months, it’s a gargantuan improvement on Gladwell’s hideous promise of 10,000 hours.

What’s more, studies in both science and psychology are repeatedly showing us new, or at least more nuanced, ways of approaching learning. These refined tactics and strategies are able to help us become proficient, expert, masterful, or at least good in a specific domain in a lot less time than we might suppose.

Let me give you just a few of these.

By creating a feedback loop (or a smart feedback loop), you’re creating a way to more accurately spot your errors and identify potential improvements that are having an effect on your learning. One study conducted at Brunel University, UK explains:

“A feedback loop [provides]…the necessary information for adaptive measures to achieve the desired levels of teaching and learning objectives.”

Acquiring the necessary information to get to a desired objective is precisely what rapid skill acquisition is about. It’s about finding out exactly what you need to change to reach your goal more quickly.

For some skills, you’ll be able to track results and measurements yourself. You could throw together some useful Google Forms to provide you with feedback, then adapt your approach based on the results.

For other skills, you’ll need feedback from elsewhere: a mastermind group, for instance.

If you’re learning programming, submitting your code to communities such as Code Review will provide you with valuable feedback about how to improve.

If you’re learning photography, there’s a Photo Critique subreddit for that.

There are similar communities and forums for virtually anything you want to study. The experts in each of these offer an invaluable feedback loop to keep your skills improving faster than simply practicing over and over.

To go back to Anders Ericsson, much of his research has been focused on Deliberate Practice, which I’ve discussed before, and the following video explains it well.

In the article mentioned I explored Deliberate Practice, which is seen by some as one of the most efficient ways to learn. That is, to focus very deliberately on the sub-skills that make up an overall skill.

To delve even deeper in this topic, read Cal Newport’s blog, StudyHacks. To quote that article:

“By choosing a specific aim (i.e. becoming an expert WordPress programmer), you can clearly see the sub-skills that are important to master in order to help you achieve this aim — PHP, CSS, etc. Each of these individual sub-skills, of course, can be broken down into further sub-sub-skills. By deliberately focusing on mastering each of these sub-sub-skills individually, you can become an expert WordPress programmer.”

Based on his research on Deliberate Practice, Ericsson writes:

“The effects of mere experience differ greatly from those of Deliberate Practice, where individuals concentrate on actively trying to go beyond their current abilities.”

Unsurprisingly, Deliberate Practice is hard. Ericsson found that elite athletes, writers, and musicians could only sustain the concentration needed for Deliberate Practice for relatively short periods of time. Their concentration on very specific skills, however, ensured they continued to improve and perform at the top of their game.

You can even find tools and apps for tracking deliberate practice in the key areas of your life. Or just repurpose the tools around you.

For e.g. get better at presentations by video capturing your performance with a smartphone. Alternatively, you can search for specialized tools like SpeechMaker.

The web is full of educational games and tools for different skills. Use tools like Anki for learning any new topic. Try deliberate practice for learning programming. And then practice live coding interviews with new tools like Pramp or interviewing.io.

Look around and start the marathon.

The idea of learning through teaching isn’t new. But after a certain amount of research, the National Training Laboratories felt confident enough to release The Learning Pyramid. This is a simple diagram showing the very rough retention rates to be expected through various forms of teaching. The pyramid has its opponents, but for many, it remains a reliable guideline.

As you can see, the passive learning approaches offer relatively low levels of retention. Unfortunately, this is what we often rely on when picking up a new skill, especially as adults.

The participatory methods, however, offer much more promise. The “Group Discussions” (50% retention), as mentioned previously, could be fostered through mastermind groups or online critiques. “Practice by Doing” (75% retention) is where Deliberate Practice comes in. But with “Teaching Others” reportedly offering a 90% retention rate, we can’t ignore this strategy.

“If you can’t explain it to a six year old, you don’t understand it yourself.” –Einstein

Whether you’re already proficient, or a complete novice here isn’t important. If you’re an expert looking to improve, you have a lot to teach. If you’re a novice, you can explain what you’re learning to others.

Harry Cloudfoot, for instance, documented his journey to become a “very good” rock climber using many of Tim Ferriss’ methods. Many of his posts read as lessons that others could follow.

Taking this approach means that you have to truly understand a very specific area of study before being able to teach it to others. This gives you the motivation and responsibility to really get to grips with that topic.

If you’re at an advanced level, you could use sites like Private Tutoring At Home to find tutoring gigs. If you wanted something with less responsibility, you could answer relevant questions on Quora, Reddit, or a subject forum.

One favorite option is to start a blog where you can publish posts explaining your findings, methods, and results. If you want to write posts, but don’t want to set up a blog, you could write on Medium, or even start a private Facebook group and invite people to join. There are plenty of options.

As I’ve explained, Gladwell’s 10,000-Hour Rule is based on very unstable foundations. Luckily for us, the alternative is far preferable.

By paying close attention to how you spend your practice time you can accelerate your learning so that a skill could be mastered in much less time than you think, provided your efforts are smart and deliberate.

You can do this by introducing reliable feedback loops, Deliberate Practice, and an aspect of teaching, into your learning regimen.

What other learning methods and techniques have helped you to accelerate your learning?

Image Credits: man practicing rock-climbing by Nejron Photo via Shutterstock, The Learning Pyramid via WorldBank.org

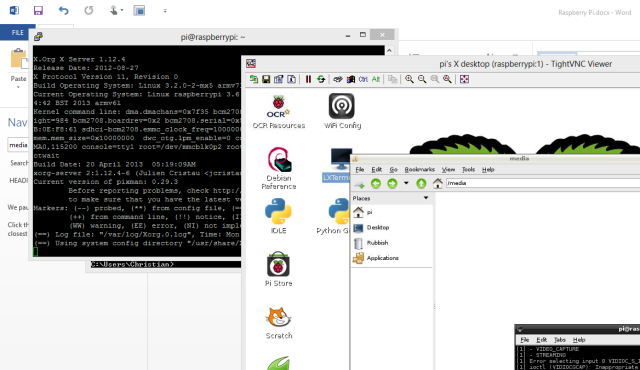

How to Run a Remote Desktop on Raspberry Pi with VNC

How to Run a Remote Desktop on Raspberry Pi with VNC Top 10 Best RPGs for Xbox 360

Top 10 Best RPGs for Xbox 360 The Best Star Wars Books All Fans Need to Read

The Best Star Wars Books All Fans Need to Read Top 5 Most Wanted Unlikely RPG Sequels

Top 5 Most Wanted Unlikely RPG Sequels Fallout 4 Settlement Building Walkthrough

Fallout 4 Settlement Building Walkthrough