Digital Rights Management, or DRM for short, has been a hot-button topic over the past few years. The proliferation of online connectivity has made it easier for publishers to justify various measures that force players to login to play or periodically check a game’s validity with a remote server.

Yet DRM isn’t a recent invention. There are games twenty years old that try to throw off hackers, pirates and thieves through various means, some of which are devious or downright evil. Pirating a game is easy – except when the games retaliate!

Although not explicitly designed as such, early consoles were effectively a form of DRM. By using proprietary cartridges, rather than a commonly available format (like the floppy disk), console makers effectively crafted a form of physical copy protection.

This didn’t stop for-profit bootleggers, of course, but it did stop the average person from copying games on their own. The tactic was considered effective enough that, when Nintendo introduced the Famicon Disk System (an NES add-on that could play games from a floppy), the company added a physical restriction in the form of a big, fat, raised Nintendo logo. Disks without the logo would not work, even if the data on the disk was identical.

Proprietary cartridges are a pretty good way to prevent piracy, but they can be copied after some reverse-engineering, and by the 1990s companies looking to make a buck began to market devices that could copy or “backup” game cartridges, putting piracy within reach of the average gamer.

To combat this, some games inserted code which checked the specifications of the hardware running the game. If an anomaly was found, bad things would happen; the game might refuse to play, might not start properly, or might not allow you to save.

Earthbound, a famous RPG for the SNES, took a particularly evil approach. The game would appear to play normally, but would increase the rate of random enemy encounters, making the game far less enjoyable. And, if you managed to slog through anyway, the game would freeze and delete all your save data during a boss fight near the game’s end. Many rage-quits occurred because of this harsh punishment for piracy.

While the cartridges used by consoles provided a basic form of DRM, computer games never enjoyed such protection. To combat piracy, PC game publishers instead used floppy disks with unusual manufacturing features that could not be easily reproduced, but this also meant users could not make backups – an issue when you ship games on something as fragile as a floppy. Publishers wanted the best of both worlds, so they started to ship physical off-disk copy protection in the form of complex passphrases or codes.

The most well-known example is The Secret of Monkey Island’s Dial-A-Pirate, a rotating paper wheel with faces printed on it and small, rectangular cut-outs with location labels through which numbers could be seen. The game would occasionally show a face of a pirate, along with the place where they were hanged, and the player would have to rotate the Dial-A-Pirate to match the information the game displayed. Doing so would display a short DRM code through the wheel’s cut-out. Other game shipped with puzzles that had to be solved to obtain a key code. Gimmicks like this were called “feelies,” since they were physical and often had to be touched or manipulated to work.

Though creative, gamers who figured out how to solve a feelie could simply share the information on message boards, rendering them useless. Eventually, this idea gave way to the more practical CD key.

The advent of the Internet meant it was easy for people to share the secrets to hidden codes or puzzles, so another type of physical copy protection was required. Many variants appeared, but the strangest is without a doubt Lenslok.

As the name suggest, this form of copy protection used a lens that was held up to a television to decode a scrambled on-screen message. The specifically designed lens would re-direct light, making the code readable. However, this would only work if the Lenslok was held in precisely the right location, and it wouldn’t work at all with extremely large or small TVs. Whoops!

Lenslok wasn’t very popular for obvious reasons, and it was used with only a handful of games (including the famous space-fighter game Elite) in the 1980s. The idea moved on to dongles that must be plugged in to a console or computer to make a game work, which were more reliable, but still very easy to lose. Though these too proved unpopular and are no longer common, the tactic has been used as recently as 2008’s DJMax Trilogy.

The 1990s was an era of relatively light DRM. CD-ROMS were, for a time, an effective barrier against pirates because burners were extremely expensive. Eventually prices came down, but most PC game publishers responded with nothing more than a CD-key that must be entered at installation. Consoles, meanwhile, used a combination of proprietary code and hardware to thwart bootlegged copies. Both forms of copy protection were easy to circumvent, but publishers didn’t seem particularly worried.

Then broadband Internet arrived, and everything changed. For the first time in history, gamers could easily share games with others online. A single person uploading a game as a .zip file could distribute it to thousands of people. Publishers responded with online key checks, which developed into game distribution platforms like Steam and Origin.

While most modern forms of DRM simply try to prevent gamers from even launching a pirated game, some developers have baked in pranks. In Crysis: Warhead, for example, guns will shoot chickens if the game can’t validate that it’s a legitimate copy, while Serious Sam 3 pits pirates against an invincible scorpion. Games which pull pranks like this usually do so when an online validation check fails, or when the game detects that its DRM has been removed completely.

Though these gags are amusing to watch on YouTube, they highlight the downsides of modern copy protection. Creating a backup copy can be very difficult, if not impossible, and attempting to do so may simply trigger DRM. Some of the worst offenders, like SecuROM and StarForce, have been known to malfunction for no real reason at all, or because CD-burning software is present on an “offending” PC.

Consoles are not much better. While hackers and pirates continue to get around each console’s built-in DRM using modified hardware, these modifications can be detected and lead to a ban from using online services like Xbox Live. Worse, hardware modification can trigger a ban whether they’re used for piracy or not. Today’s consoles are more like PCs than ever before and, as a result, theoretically easier to hack – but the punishment for mods has become too high for most players to risk.

Some might say that we’re in a dark age of DRM. Certainly, the tactics used today seem draconian when compared to CD keys. But perhaps things are not so bad, because copy protection in the 80s was also pretty severe, and wasn’t offset by digital storefronts offering games at absurdly low prices.

What do you think about DRM’s current direction – and where it might head in the future? Sound off in the comments!

Image Credit: Bryan Ochalla/Flickr, Hector Sanchez/Flickr, CPC-Power, Final Boss Blog

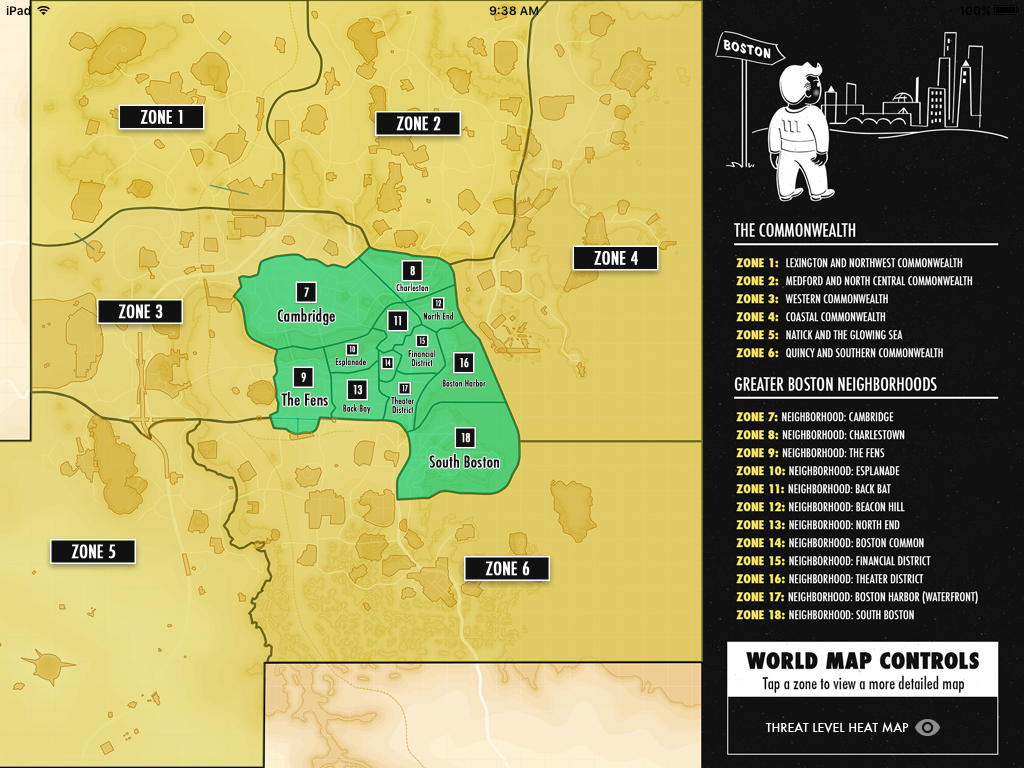

Fallout 4 Guide: All Bobblehead and Magazine Locations With World Map - Spoiler Fee

Fallout 4 Guide: All Bobblehead and Magazine Locations With World Map - Spoiler Fee Fallout 4 Guide: S.P.E.C.I.A.L., Perks and Character Build Strategy Guide

Fallout 4 Guide: S.P.E.C.I.A.L., Perks and Character Build Strategy Guide What You Need To Know Before Buying A PC Or Console Racing Wheel

What You Need To Know Before Buying A PC Or Console Racing Wheel Gravity Rush Walkthrough

Gravity Rush Walkthrough Gears of War 3: RAAM's Shadow Achievements List

Gears of War 3: RAAM's Shadow Achievements List