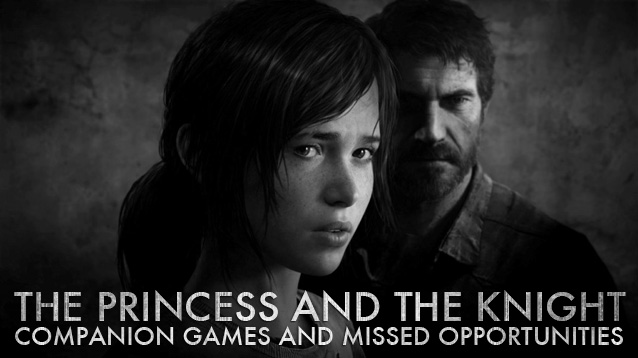

Something has been bothering me lately, and it has to do with missed opportunities. It has to do with Ico and Yorda. It has to do with Gordan and Alyx. Monkey and Trip. It has to do with characters we don’t even know yet. Characters like Joel and Ellie. Companions like Booker and Elizabeth.

Some of the best video game experiences in the last decade have been those that cultivate and develop a relationship between two main characters, games that take the time and effort to craft a believable and intimate bond between ramshackle duos that must travel together through vast, hostile and unforgiving worlds - and come to know and trust each other through their trials and tribulations.

When Naughty Dog unveiled their new intellectual property The Last of Us at Spike’s 2011 Video Game Awards, many were disappointed the narrative focused on yet another post-apocalyptic world overrun with zombie-like creatures, but just as many were just as fascinated with the immediate chemistry between the two title characters, Joel and Ellie. At that time, which of the two characters we would play as was still up in the air, the game still ripe with potential and possibility. Now that more details have recently been offered, one of those possibilities has already been foreclosed. At least in the single-player campaign, we would be playing as Joel.

Why isn’t Ellie the main playable character in The Last of Us?This disappointment made me ask a question that quickly spiraled into a series of questions and ultimately into a disturbing realization of a distinct trend. First, why isn’t Ellie the main playable character in The Last of Us? Second, what other games that feature what I will call “companion” narratives and designs have also chosen not to allow people to play as the female character, and why does this trend seem so consistent over so many of these experiences? I started to tally these games up in my head. Ico. Half-Life 2 and its subsequent episodes. The Prince of Persia reboot in 2008. Enslaved: Odyssey to the West. And in the near future, The Last of Us and BioShock Infinite. All of these games feature male and female companions that must struggle together against all odds through inhospitable environments to survive, and all of these games limit the player to the male perspective.

For those unfamiliar with these types of game experiences, what I am calling companion games traditionally feature two characters traveling through virtual worlds, solving puzzles, avoiding or defeating enemies, and always heading toward a distant yet important geographical location or goal. For example, in Ico a young horned boy must lead a tacit and ephemeral princess literally by hand to safety by trying to escape the castle-prison where they are confined. Likewise, while the power struggle between Monkey and Trip in Enslaved is more complex, the player as nomadic acrobat Monkey must still act as protector and guide to the former prisoner Trip as she attempts to return to her village far from the ruins of the city where they start their adventure. By all accounts, the narratives of The Last of Us and BioShock Infinite feature similar scenarios where a male protector is charged with the care and rescue of a vulnerable yet immensely important female character. It seems for all our modern gendered sensibilities (and I say this with a pinch of sarcasm), the same story of the princess and the knight still creeps steadily into popular culture.

Without getting into Laura Mulvey’s flawed but intellectually important screen theory which hinges on the viewer/player adopting a male gaze, or the discursive matrix of masculinity formed when these scenarios are repeated ad nauseum in cultural texts, or even a critical feminist reading of any individual companion game and the various ways these narratives support patriarchal structures, gender inequality, and female powerlessness, I want to stress that these decisions, the choices developers make to continually place agency and player perspective with the men in these adventures, and the deliberate adoption of what are now tired fairytale scripts have real consequences for the industry, for the cultural imagination of gender politics, and for what forms video games can even take. So when I say this trend disturbs me, I am not speaking lightly.

As much as this trend is tied to the relative dearth of female lead protagonists in video games across the board, I do not want to conflate the two issues. Although it is true that there needs to be more strong female leads (not to mention more non-white and queer leads!), I want to limit my current critique to the choice, made again and again, in male and female companion games to persistently give the player control of the male character. In other words, we need to pick our battles.

To be sure, many out there will probably point to narrative necessity to rationalize the continued use of this trope. The story of Half-Life 2 is Gordon’s story, after all, so why would you play as Alyx? Or in another case, Ellie’s status as special and unique acts as a linchpin in the narrative of The Last of Us, so it only makes sense—doesn’t it?—to ask to player as Joel to protect her.

Are developers letting their game design dictate their stories or their stories dictate the game design?You know, for the good of humanity.

However well reasoned, to this justification I say: then change the narratives! Are developers letting their game design dictate their stories or their stories dictate the game design? In either case, more imagination in both design and narrative needs to be exercised in order to break this unconscious cycle.

Here is an exercise in imagination: Instead of Drake starring in the next Uncharted game, accompanied by his ragtag posse of Sully, Elena, and Chloe, the story follows Elena as she investigates the disappearance of her current (or will it be former?) husband. I mean, she is an investigative journalist, right? We already know she can handle a firearm and scramble up the deteriorated side of any building or cliff, and we know by the way she goes toe-to-toe with Drake that she has the wit to carry an Uncharted game, known for their random character quips during gameplay. So what’s stopping this decision? What’s stopping Naughty Dog from making Elena or Ellie the central protagonist in either The Last of Us or Uncharted’s diegetic worlds? One possible answer: Imagination.

Lacking imagination, we need to ask ourselves some hard questions.

What assumptions do we reify when we craft narratives and design games around the gendered assumption that men should protect women?

What worlds and what possibilities do we foreclose by uncritically celebrating these decisions?

Look back at the first paragraph. Did you even notice that I listed the male name first when referencing all the famous video game pairs? Neither did I until now.

Imagine a twist in BioShock Infinite where half-way through the game, the roles of Elizabeth and Booker are reversed and the player takes control of Elizabeth to guide and protect her former rescuer, where the player is allowed to see male frailty in his or her companion through the eyes of a woman. Hell, imagine a world where Booker is a woman to begin with! Imagine a world where Yorda saves Ico, where Trip guides Monkey to the Promised Land.

I want to immerse myself in an experience where a teenage girl can be the hero, where she can protect the rugged, battle-weary man, where she can reverse or explode the gendered myth of the princess and the knight.

DmC Collectibles Location Guide (Lost Souls, Keys And Secret Doors)

DmC Collectibles Location Guide (Lost Souls, Keys And Secret Doors) How To Play Railroad Tycoon And Similar Games On Android

How To Play Railroad Tycoon And Similar Games On Android How to Beat Old Dragonslayer Boss in Dark Souls 2

How to Beat Old Dragonslayer Boss in Dark Souls 2 Where are all Legendary Weapons and Armor in Fallout 4 and What are their effects

Where are all Legendary Weapons and Armor in Fallout 4 and What are their effects The Talos Principle Walkthrough

The Talos Principle Walkthrough