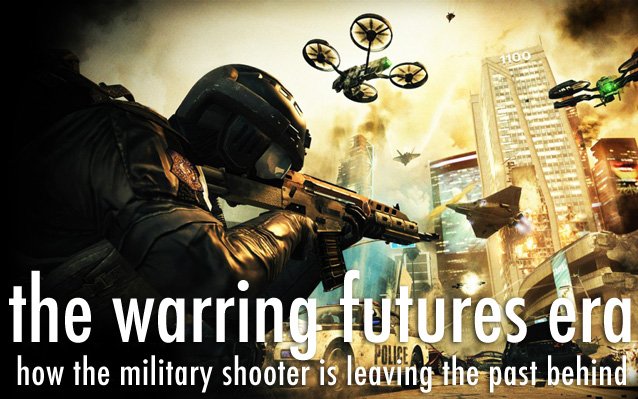

The Future is Black. That’s the slogan to the upcoming new entry in the mega-selling Call of Duty franchise, Black Ops II. After numerous tours of duty through the battles of World War II, a few years spent in (fictionalized) modern-day conflicts, the military shooter genre is finally going places nobody has seen before. It’s embarking for the future--the near future at that.

Call of Duty is not alone in this. Another release this year is a new entry to the not-quite-so-massively selling Ghost Recon franchise, dubbed Ghost Recon: Future Soldier. Both games are set in the near future, focusing more or less heavily on drone warfare and other futuristic gadgets. It might seem like a new phenomenon, but there have already been a number of entries that took the player to battlefields just around the corner such as last year’s Homefront, for example.

However, it takes Call of Duty, the elephant of the genre, to take pseudo-sci-fi near future into the mainstream. And with that there are some interesting implications. This kind of near-future military sci-fi has already been done by a few titles, most notably Ghost Recon: Advanced Warfighter, which had the player control unmanned aerial vehicles and other drones alongside hyper-modern tactical battlefield planning gadgets. But the tools given to the player aren’t the most interesting aspects of these games. In the end, all those titles are videogames, and implementing fancy GUIs for tactical planning are just a way of rooting videogamey elements in the real world.

This is of course another interesting implication: when actual war hardware takes notes from videogames, only for that hardware then seeing implementation as another game mechanic in a videogame. That aside, what’s really most interesting is the fiction behind the conflicts these games envision.

The near future has a lot of potential for politically charged military fiction. Wars involving Russia, China and South America (for example) could exist on the horizon. The ArmA series already featured China as an opposing force extensively in its recent iterations, although they didn’t feature many of the newfangled technical gadgets this new generation of shooters promises. Conflicts involving Sub-Saharan Africa are another issue, with the potential to feature interesting, scarcely used, and fresh locales rife with conflict.

Sadly, most of those games don’t seem to be interested in presenting the player with moral grey areas.Sadly, most of those games don’t seem to be interested in presenting the player with moral grey areas. Take Africa for example, and imagine an American Covert Ops campaign. But against who? Maybe against the Chinese getting a foothold in resource rich countries? That is an interesting conflict, but it shouldn’t be glossed over that a conflict like that usually has the local population bearing the brunt of any hostile exchanges, especially when either side starts recruiting or supplying local militias.

Maybe some will argue players aren’t interested in these kinds of issues. People are interested in playing heroic characters, not faceless soldiers deployed by their government to do corporate dirty work and secure Big Oil’s footing in whatever corrupt backwater country the conflict takes place in. However, raising these issues is crucial if mainstream games will ever matter, even if those issues are just raised as an aside. In the past, games set in modern times only reluctantly skirted current conflicts in favor of completely fictional ones. When Medal of Honor tried the waters of a more realistic backdrop with a game set in the current Afghan war the public backlash was huge. Konami’s big shooter project Six Days in Fallujah was dropped by the publisher due to the game’s controversial subject matter.

It’s perfectly valid to say that a game set during an ongoing war might be too controversial and strike too close to home. However, this isn’t an issue for a game set in any near future setting. Looking at the world today and at the many potential conflicts, coming up with a realistic scenario that’s both interesting enough to base an exciting shooter around and important enough to make a statement isn’t too hard. The medium is more than ready to have its Apocalypse Now, its Deer Hunter, its Platoon.

And that’s where the sad, corporate reality of modern games comes in. Call of Duty surely won’t do such a thing. While the series is now famous for shocking set pieces Activision isn’t ready to face this kind of controversy. They have already positioned themselves clearly by using Oliver North in their promotional videos; this is a controversial step, but not in a relevant direction. At this point, the gaming industry is too risk-adverse to tackle anything not taking place in the weird, self-referential realm of videogames.

Modern Warfare 2’s “No Russian” mission was one such false controversy. While high on shock value, it ran no risk of asking players to think about the real world implications of actual modern warfare. The same will most probably be true of Black Ops II. It will be filled with shock and awe, but little actual substance. In a sense their slogan is right: the future will indeed be black, but it will also be white. And if games are to have any meaning at all, they must embrace all the shades of grey in between.

How to get the 5 Best Destiny Hunter Gauntlets

How to get the 5 Best Destiny Hunter Gauntlets How to Built a Perfect Character: Fallout 4 Guide

How to Built a Perfect Character: Fallout 4 Guide The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt How to - Beginner's Combat Guide

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt How to - Beginner's Combat Guide How To Get Destiny Strange Coins To Buy Xur: Agent of the Nine Exotic Items

How To Get Destiny Strange Coins To Buy Xur: Agent of the Nine Exotic Items Civilizing Video Game Culture by the Sword

Civilizing Video Game Culture by the Sword