Corey Milne has an interesting concept of taboo. When controversy arose around Tomb Raider's choice to have a criminal sexually assault Lara Croft, the people of the Internet, who use points they've missed as a form of currency, saw this as an opportunity to deliberate what should and shouldn't be in games.

Milne explores this in his article, "5 Weird Places No Video Game Should Go." With all due respect to Milne, he struggles with consistency throughout, however, even managing to twist out contradiction in his opening. He was quick to note early on that rape isn't on this list, explaining that, because games are an evolving medium, a mature and intelligent approach can make rape an acceptable topic. His confidence in games is laudable, because one can argue that an artistic medium should freely be able to tackle any subject. Unfortunately, this, at best, discredits his article as a whole and, at worse, implies that rape requires less intelligent and mature analysis than any of the subjects on it.

An artistic medium doesn't evolve after a lazy afternoon of self-discovery, it evolves after it sets new standards, and saying that these concepts are places where "no video games should go" is incredibly irresponsible. It intellectually neuters the medium, and insults the audience by implying that they lack the ability to engage with the idea. Fear not though, dear reader, for after after much soul-searching (i.e. applying a modicum of critical analysis) I am able to discuss why these are five things games absolutely should discuss.

A good storyteller never does anything for the sake of itself. In a story where a character can kill without a sense of consequence, that is a facet of the character that can be explored, either through gaining understanding of why they think that way or by showing their change and development from that over time.

A mature, critical story can handle this well because a mature, critical story doesn't require its audience to agree with its characters. The most potent part of the gaming medium is its ability to Being John Malkovich players into another entity, allowing them to see a world outside of their own experiences. There is enormous potential here to explore extraordinary concepts, including a character who supposedly kills "for the sake of killing" who could be played as a learning experience for the player.

The “No Russian” instance of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 cited by Milne wasn’t just for the sake of killing. While the series isn’t famous for nuance, it was a moment where players had to decide whether or not they would participate in the killing of innocent people. The consequences fell to the player themselves and the immersion they had in it. It’s not a defense of the segment of the game, but there is a degree of internal accountability. Grand Theft Auto IV, another example that Milne uses, however...

As a reasonable human being, whenever someone mentions feminism, I generally don’t condescend to them and use pseudo-facetious masculinity as thinly-veiled bigotry. Unfortunately, this isn’t the usual response. “Feminism” is a word that, to many, means troublemakers. In a large sense, that’s true. Feminists are rabble-rousers who upset the status quo. It’s a movement, and that is defined by the fact that one isn’t sitting still. While it comes in many forms, it isn’t “that thing from the sixties;” it’s an ideology that means addressing the unbalanced whenever and wherever it exists.

And in games, it exists. Right now, developers born in the sixties of feminism past are developing games, and they are built with the teenage power fantasies that Milne accredits to modern developers. Few would deny that women in games are portrayed poorly, but excuses are offered over solutions. Milne himself says that women “stuff” should be tackled only after more women are in the industry and it can be handled more maturely. This is almost elegantly wrong, if not for the fact that it is so insulting. His contention would have “women stuff” unaddressed, allowing the medium to stay festeringly frat and utterly unwelcoming to women.

Milne also argues that a person can rape another person in a game and it is acceptable narrative if told maturely, but the idea that people should be treated equal is just not something an audience can handle? That is catastrophic.

Much like how killing isn’t always just about killing, sex isn’t always just about being sexy. Sex can represent a lot of different things to a lot of different people. Sex is a form of relating to other people, and it’s as dynamic and as diverse as any other form of relationship. Games have a tendency to be pretty immature with it, but they aren’t incapable of demonstrating adult relationships.

When Milne discusses his concept of sex as being ridiculous in games, he highlights ridiculous examples, while ignoring the possibility of mature examples. As awkward as it is, Heavy Rain tries to depict sex as adult, without the implicit goal of titillation. When Naked Snake and EVA have sex in Metal Gear Solid 3, it isn’t meant to be some sexy romp, it’s a finality in character, and a breaking down in Naked Snake’s guard. Games and their developers realize that it is something that people do, without trying to turn it into a reward, or transform it into some erotic, vulgar envelope-pusher. They have it because it is appropriate to the story.

These developers aren’t too insecure to show adults having an adult relationship. The idea of being so terrified of sex, and yet so comfortable with violence shows a fundamental flaw in the values that people hold. It’s incomprehensible that Milne would say that sexual violence is a potentially acceptable theme in games, while sex itself, and its many consented forms, are unacceptable.

Nearly thirty years ago, the final episode of M*A*S*H aired. Lots of people saw it. In fact, if you owned a television back then, it probably was more likely that you saw the episode than not. The episode had Hawkeye Pierce, Alan Alda as leading man, struggling with a woman who killed a chicken to keep it from making noise while enemy soldiers walked past them. Not to spoil the three decade old show, but it turns out that the chicken was just Hawkeye replacing the woman’s baby in his mind. It is a potent plot point that breaks a previously unbreakable character, and has become one of the most iconic television moments of all time.

The power behind the storytelling in games is that, when actions are taken, they have to be taken by the player. Imagine a game where that isn’t a requirement, but an option. Imagine the M*A*S*H finale. Imagine Sophie’s Choice. Imagine a scenario where enough gravitas is put on to the life of a child, and, as a player, you have to decide whether to take that life or not.

If the stage is set where killing the child is about impact and effect rather than just shock value, and if it is handled in a way that doesn’t diminish the morality of it, then the murder of a child can be important.

There could be no other number one than this. Torture in real life is as unforgivable as anything else on or off the list, isn’t it? It strips a person of all ability to defend themselves. It’s willpower against harsher conditions than anyone should ever have to face. It’s valid, because it is, unlike most anything else on the list, a legitimately difficult subject to tackle. What can justify torture in a game?

The same can be asked of real life. The fact is, people have and do torture others in real life. It isn’t just sociopaths, torture experts have been people who do that during the day, then go home to their spouse and children at night. It’s easily possible to justify those people as being purely monsters because they perform the work of monsters, but what if they aren’t?

Take, for example, a war game. A person interrogates someone for information, due to propaganda, due to dehumanizing the enemy, and due to desperation for protecting one’s own. A game can expose the grisly nature of war on a much more gruesome level than giving numbers, or gunning down faceless AI. It can give a face, a personality to the enemy. The player can see a strong-willed person with conviction, and be forced to break them down.

It can carry a message against war itself, or against the way mankind chooses to wage it. If a developer is capable of respecting games as an artistically-capable medium, they can show that the system of war forces good people to do horrible things, and that it forces them to do it to good people.

If you respect that games are a medium that are maturing and evolving, then the idea of a controversial idea should be exciting, not frightening. Throttling games with anything on this list is only telling of one’s own insecurities and ignorances. It is a medium that, developer and audience-willing, can provide a unique platform for new experience and new perspective.

Video games can be a path to enlightenment if we’re willing to follow.

How to use the Mortal Kombat X All Hidden and Secondary Secret Fatalities

How to use the Mortal Kombat X All Hidden and Secondary Secret Fatalities Fallout 4: Cure / Avoid Mole Rat Disease - tips

Fallout 4: Cure / Avoid Mole Rat Disease - tips Pokemon X And Y: Things We Do NOT Want

Pokemon X And Y: Things We Do NOT Want Bloodborne: The Old Hunters - How to Get the Bowblade

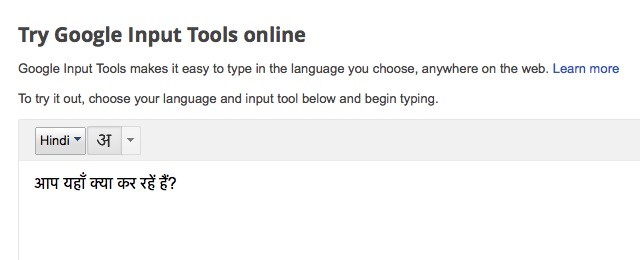

Bloodborne: The Old Hunters - How to Get the Bowblade 3 Lesser-Known Google Services That You'll Find Useful

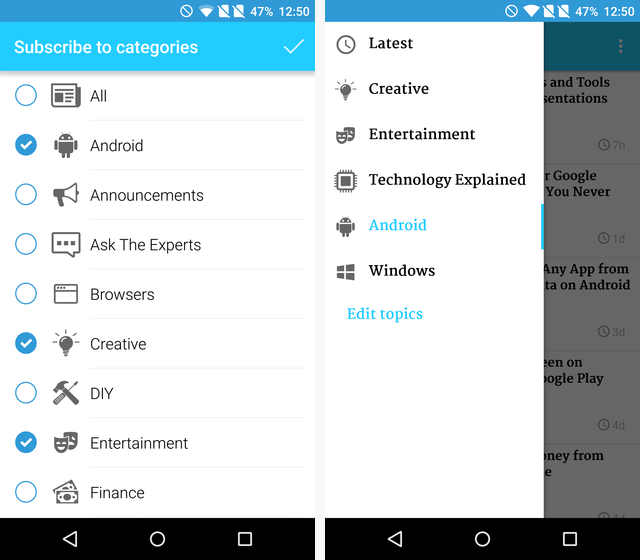

3 Lesser-Known Google Services That You'll Find Useful