Last week I wrote about Binary Domain’s trust mechanic and how it originally starts out as just a ‘gimmick’ to distinguish Binary Domain from every other shooter but, by the end of the game, works wonders to meld the gameplay and the narrative together. It managed to mesh the events of cut scenes and the gameplay skirmishes together seamlessly so that I actually felt the exclusion that my character himself felt.

Another feature that starts off as just another gimmick before going somewhere really special is the game’s voice recognition. Orders can be shouted at your squad during battles using that headset you typically only use for multiplayer games, telling your NPC squad to “Attack!”; “Fall back!”; or “Cover me!”.

It’s not an entirely new gimmick, to be sure. The SOCOM series on the Playstation 2 tried to do a similar thing and, completely unsurprisingly, it works fairly terribly on both accounts. Maybe it is better for those with American accents, but in Australia, ‘Just add voice recognition’ is about as likely to make a game better as ‘just add gesture controls’. It’s the kind of thing that, superficially, is going to detract from the game more than it can possibly contribute.

It’s not an entirely new gimmick, to be sure. The SOCOM series on the Playstation 2 tried to do a similar thing and, completely unsurprisingly, it works fairly terribly on both accounts. Maybe it is better for those with American accents, but in Australia, ‘Just add voice recognition’ is about as likely to make a game better as ‘just add gesture controls’. It’s the kind of thing that, superficially, is going to detract from the game more than it can possibly contribute.

I tried Binary Domain’s voice controls for all of ten minutes before I got fed up with shouting the same phrases at a dozen different paces and cadences without comprehension from my squad mates. Even when it did work, it just felt kind of pathetic, shouting at my single-player game. For a lack of a better term, it was just too geeky and weird, and it wasn’t contributing anything to my experience.

Fortunately, though, there is the much more tolerable option to just hold down a button and choose an order from a list of commands. Once I gave up on the mic and embraced this, I found myself far more likely to stop and see just what commands could be given to my squad at a given time. I was far more likely to actually engage with these people.

It doesn’t take too long before you realise this voice system—with or without real voices—is not really a command system so much as a conversation system. Not only can you bark orders during skirmishes, but you can have conversations during the down times. These conversations allow you to build up trust with the disparate members of the Rust Crew. It’s nice to see that the voice used to bark commands in battle is the same voice used to get to know people socially. It allows the two sides of these social relations to gel nicely.

But even still, for most of the game this system feels tacked on. After shooting through a hundred robots, one of your squad mates might ask you a yes/no question like: “I sure could go for a beer after this is all done, Dan. How about you?” You answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The answer you need to say to make them trust you most is pretty blatant.

Sometimes a third option is possible. Usually this option is some kind of joke. Something that would be an absolutely absurd answer to the question asked, like “I love you” or “God damn it!“ You know it isn’t the right answer, you know your trust will go down, but it receives some awkward responses that can sometimes be humorous. Sometimes. It’s like a tacked-on feature of this tacked-on system.

But just like the trust system, the voice commands/conversations suddenly and covertly come to greatly affect my engagement with the later part of the game. While the trust system was manipulated in a way to change the overall feel of being part of my squad for the final hours of the game, the voice system powerfully affected one particular moment in an unforgettable way.

After Faye finds out she is a Hybrid Person, she confronts the Rust Crew and starts a fight with them. Dan is conflicted. He has feelings for Faye. He considers her a human and doesn’t want to kill her. But Faye already feels betrayed by the Rust Crew and has climbed to a second floor balcony and is taking shots at us with her sniper rifle. “This is all a mistake!” I remember thinking, “Why can’t we talk this out?”

For the longest time I refuse to shoot at Faye. Dozens of robots are attacking us, too, and I focus on wiping them out instead, refusing to fire at this woman that Dan made love with in an awkward videogame cut scene several hours earlier. But it wasn’t just because Dan had sex with her that I didn’t want to kill her. She was one of us! I was invested in her. It seemed wrong to have to end her life now just because of who her mother is.

During the battle she starts talking to me, much like team members often do during battles. “What’s wrong?” she asks me. “You’re here to kill me, aren’t you?”

I hold down Left Bumper to see the options I can respond with:

“Yes”

“No”

“I love you.”

That’s right. “I love you.” Here, in the middle of a boss battle in a cover-shooter, I can scream out “I love you!” at the person I am fighting. Here is this tacked on conversation system, and here is this tacked-on third option that has been used before only as an awkward, eye-roll-worthy joke throughout the game. But now it means something.

That’s right. “I love you.” Here, in the middle of a boss battle in a cover-shooter, I can scream out “I love you!” at the person I am fighting. Here is this tacked on conversation system, and here is this tacked-on third option that has been used before only as an awkward, eye-roll-worthy joke throughout the game. But now it means something.

I press the corresponding button, and shout “I love you!” at Faye, at the boss, at a woman I made love with.

She doesn’t believe me. “Give me a break,” she says. “You’re all here to kill me.”

I can speak again, and I have the same three options: “I love you!” I press.

I can’t help but imagine what this would have been like if I had tolerated the voice-recognition option for the whole game. I can’t imagine what it would be like, after hours of shouting “Fire!”; “Attack!”; “Yes”; and “No”, to start shouting “I love you!” at my TV set in a vein attempt to stop a boss fight. I would have to shout it over and over, not just twice, as I try to get the damn game to recognise what I am saying. I would be sitting there desperate for her to hear me and stop shooting at me.

I doubt many players actually tolerated the voice-controls for that much of the game. But someone out there, I don’t doubt, has had a phenomenal experience with this fight, professing their love to a character they don’t want to kill.

The best part is that it actually stops the fight. Not for long, sadly, but when you say “I love you” that second time, the fighting momentarily stops. And suddenly, voice-controls aren’t just a gimmick anymore. I don’t know what happens in this fight if you don’t answer with “I love you.” Maybe nothing changes at all. I don’t think that is really relevant. For this play through, I was able to tell someone I loved them instead of trying to kill them, and it ended a battle.

Just with the trust system’s ability to make me feel excluded from the Rust Crew, the command/conversation mechanic allowed me to have an actual, strong emotional connection with a character, and to actively invest in that relationship during gameplay. It was no longer just the fact that Dan had fallen in love with Faye during cut scenes. Here I was able to decide that I cared for her, too, by telling her how I felt and trying to get the fighting to stop.

Binary Domain is a game full of surprises and double-takes. It builds your expectations up and subverts them in interesting way, both with its story and its mechanics. It’s in the way it makes you feel empathetic for the hollow children. It’s in the third-act introduction of hybrid people. It’s in the ‘trust’ system that actually made me feel excluded from a group of people. But in the end, I can’t think of any scene that exemplifies Binary Domain’s unexpected ability to move me more than a boss battle against an entirely organic woman classified as non-human being halted by screaming “I love you!” For a game about binaries, Binary Domain is anything but black and white.

PS4 Role Playing Games List

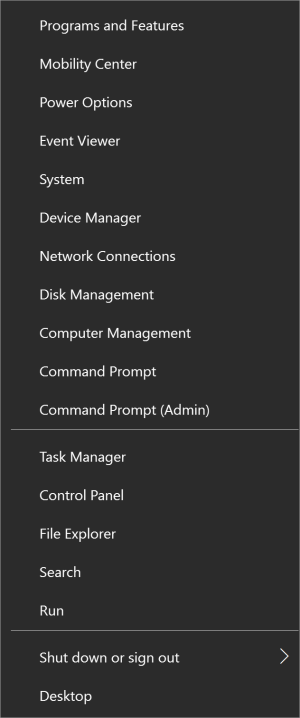

PS4 Role Playing Games List 10 Neglected Windows Superpowers & How to Access Them

10 Neglected Windows Superpowers & How to Access Them Fallout 4: How to Pick Locks

Fallout 4: How to Pick Locks Metacritic Scores are Ruining Videogames, Just Ask Obsidian

Metacritic Scores are Ruining Videogames, Just Ask Obsidian Destiny Wanted Bounty Location Guide For June 7-June 13, Six Old Bounties Returns

Destiny Wanted Bounty Location Guide For June 7-June 13, Six Old Bounties Returns