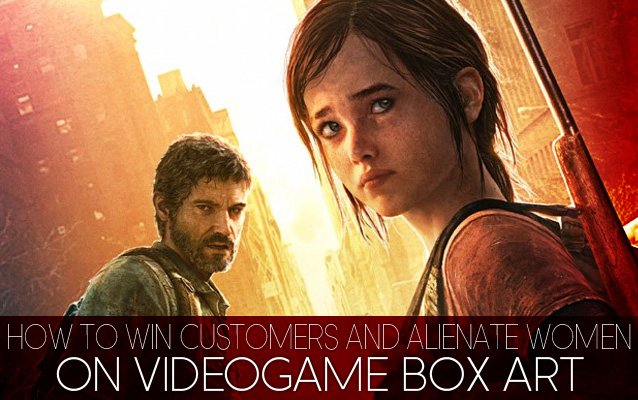

Several weeks ago, Square Enix reported on the performance of their major properties and predicted an “extraordinary loss” on this year’s sales. Surprisingly, Tomb Raider made their list of disappointments, despite moving 3.4 million copies in a month. The fact that Square Enix perceives this as “poor” speaks of the high production costs behind the development of any big-name videogame. And Tomb Raider—a project nearly five years in the making—is certainly one of the biggest names in the industry.

Anyone who has heard of the Tomb Raider reboot has likely encountered its controversies. The game’s release has done little to quiet the criticisms of “rape” and “torture porn.” This continued resistance to the game points to another cause behind Lara Croft’s inauspicious rebirth: the marketing. The spark which ignited the firestorm, so to speak, was the infamous “Crossroads” trailer that debuted at E3 this past summer. In brief, the trailer is a montage of moments where Lara falls down things, falls off things, acquires injuries, and begs her adult male friend to come and rescue her. She accomplishes all of this with many a squeal and a scream, some of which are rhythmically cut to the throbbing bass of the music. The cries highlight Lara’s anguish in a way that is both excessive and suggestive—they turn the violence inflicted upon her into a spectacle. As such, the sounds alone make the accusations of “torture porn” highly reasonable.

Of course, it’s impossible to reference the “Crossroads” trailer without also discussing the scene which inspired concerns about the attempted “rape” of Lara. Producers later clarified that this scene plays out the first time Lara kills an enemy, and it was meant to highlight Lara’s reaction and emotions more than the attack itself. Despite this, the trailer glosses over Lara’s emotional response. In flashes, it illustrates a struggle for a gun, implies (but does not show) that Lara manages to defend herself, and then cuts to Lara, covered in blood, staggering away from a prone body.

This is a strategy employed throughout the trailer. On several occasions, we see Lara raise her bow or gun to deliver a killing strike, but not once does the trailer actually depict what follows. We never see an enemy hit the ground as a result of Lara’s self-defense. This stands in stark contrast to the milieu of other, male-led trailers at last year’s E3, which scarcely shied away from portraying killing blows and collapsing bodies.

If the game were anything like the original trailers made it out to be, Tomb Raider would be a narrative in which the violence doled out against the heroine takes precedence over any other aspect of the gameplay. Thankfully, the game—and Lara Croft as a character—rise well above the early marketing. Make no mistake: the content of the trailer still occurs in game, but it is limited to the beginning of the story, and the lack of conscious editing means that Lara’s cries are not close enough together to make gamers question the extent of her lung capacity. Lara’s actual reactions to injuries closely resemble the expected reactions of any video game hero, regardless of their gender: she walks it off. The trailer also fails to represent the sublime degree to which Lara overcomes her fear and commands the narrative, not just as a woman but as a compelling character. This, if anything, illustrates how poor marketing choices may misrepresent the developer’s creative vision.

The shortcomings of Tomb Raider’s marketing appear most strikingly through what is absent in its early representations. Up until the debut of the “Reborn” trailer (which, sadly, did not premiere until a week prior to the game’s release), the promotional material portrays Lara as victim more than hero, emphasizing her vulnerability over her strength. Considering that these early trailers were audiences’ first exposure to the reboot, the game’s representation becomes particularly problematic for what it implies about the audiences themselves. It indicates how the producers felt that a victimized Lara Croft would be more marketable than the action hero Lara Croft. More importantly, it underscores troubling assumptions about audience expectations: male action heroes are expected to fight, to kill, while women “action” heroes must simply endure endless punishment by set pieces. In brief, the marketing strategy assumes that its intended audience will only express interest in a female character if she is systematically victimized and portrayed as inert.

Sadly, this is just one of many hiccups in the history of videogames with female protagonists. The numerous rejections of Capcom’s Remember Me continue to make headlines for related problems; companies turned down the game solely on the basis of its female lead. This past winter, Ben Kuchera of Penny Arcade also spearheaded some prominent issues in videogame marketing, noting that not only were female protagonists a startling minority, but the marketing budgets for such games were nearly half that of those with male leads. According to Kuchera, this could result in a self-fulfilling prophecy in which games sold poorly quite simply because their marketing strategies were not up to par.

This may have been the case with Tomb Raider, though it’s hard to say without any concrete evidence or insight in regard to the budgeting. Certainly, Tomb Raider as a franchise exists as a cautionary tale as much as it is an exemplary example. In action—and characterization—the game itself is a wonderful example of how to develop a strong, dynamic woman lead without objectifying her or simply making her a guy with boobs.

Tomb Raider’s publicity is also a lesson in how not to advertise that strong, dynamic woman. Though the recent trailers were more respectful in their treatment of Lara and, by extension, more faithful to the actual content of the game, Square Enix’s reports suggest that it may have been too little, too late. Clearly, relegating female leads to the role of victim is not an appropriate marketing strategy. The video game industry can no longer afford such missteps in their representations of female characters.

GTA 5 Character Trailers: Hidden Details You Missed

GTA 5 Character Trailers: Hidden Details You Missed How to get New Moon Armor Set in The Witcher 3 DLC Hearts of Stone

How to get New Moon Armor Set in The Witcher 3 DLC Hearts of Stone Destiny The Taken King: Legendary Marks guide

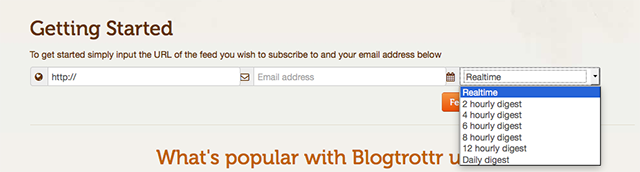

Destiny The Taken King: Legendary Marks guide 5 Apps With Realtime Notifications About Almost Anything

5 Apps With Realtime Notifications About Almost Anything Hearthstone: Heroes of Warcraft Unlockables, Achievements, Special Cards and Naxxramas Guide

Hearthstone: Heroes of Warcraft Unlockables, Achievements, Special Cards and Naxxramas Guide