Games and war, together forever; to paraphrase Avril Lavigne, could it be any more obvious? Technologies of simulation have been intertwined with the military since their earliest days. In 1980, the makers of Battlezone designed a special version for the US Army to practice its tank shooting, while today the military manshooter has product placement deals with arms companies. Wisdom dictates that games are full of combat because that's what they’re good at. How can developers design to calculate the vagaries of romance, conversation, or the human heart?

But I’m here to propose that war is actually a terrible subject for video games. Others in the community have pointed out that games usually lie to us about what war is: not a handful of heroes battling an evil horde; says James Hawkins, but a friend stepping on a landline nobody knew was there, not a winnable paintball match, says Robert Yang, but “a guard tower built next to a tennis court…a cheap internet router.” Some of the major defining characteristics of war are ones which videogames currently do very poorly indeed.

First, there’s the boredom. In Anthony Swofford’s Gulf War memoir Jarhead – adapted into a great little film in 2005 – a unit of Marine Corps snipers spend several months seeing no combat whatsoever. Nevertheless, both works ably dissect the tension, tedium, anxiety, and the jocular timewasting of military life in times of war – psychological pressures as ambiguous and complex as anything we feel on a first date. Operation Flashpoint was faithful to the sheer dullness of waiting for action, but could never fully commit, and wouldn’t be a mass-market proposition now anyway. What’s that common aphorism? War is 95% boredom and 5% terror? Try selling that ratio to a publisher.

Second, there’s the chaos. Videogames have taken the phrase ‘fog of war’ and turned it into a cute mechanical metaphor, a simple black mist to be swept away as we advance. But in real life, that phrase signifies far more. It includes all the perceptual, and organisational blindnesses of the soldier within a military machine – the soldier who has both people and white-hot exploding objects constantly demanding their attention, from above, from below, from all sides, who must take orders and give orders and interpret orders and who is subject to all the broken frameworks and biased tendencies of human cognition. For individual soldiers, war is chaos; for commanders, it’s another kind of chaos. This could make a pretty cool videogame – but common design wisdom privileges clarity, cleanness and fun over ambiguity and confusion. The industry as it stands is not well equipped to create games of such smoky diffidence.

Finally, war is simply unfair. Take for example a recent Cracked article entitled ‘The Five Most Epic One Man Rampages in the History of War’. The majority of examples involve strong elements of luck, and often the men involved died afterwards anyway. My point is not to diminish their accomplishments but rather, point out that these men could have been killed at any time. And in a million other similar cases they probably were. War is unfair, random, merciless, and sometimes people just die through no fault of their own. It's incompatible in terms of a game that makes the player the individual solider protagonist. The game is forced to either give the player unfair advantages, make the war winnable through the right button sequence or, more often, both. War is never, as Yang puts it, “fair and just in the context of a balanced game system.”

So there are three key elements of war which don’t fit well with fun design, or even with the ability to design at all. But these are just surface observations; the more enduring problem is political. The film director Francois Truffaut famously once asked whether it was truly possibly to make an anti-war film – and the question applies equally to games.

Truffaut's sentiment was that audiences inevitably find dramatized action sequences exciting. If you portray war, then in a sense you've endorsed it. The satisfying cause and effect of a well-made shootout will always provoke enjoyment: Jarhead actually includes a scene where the marines watch Apocalypse Now to psych themselves up for battle. In games, the problem is more intense. Though we try to move beyond the aspect of ‘fun’ in terms of design, players will always find ways to get what they want. As they come to grasp the game as an abstract and winnable system, the aesthetics and narrative of a system slowly fade away.

The task is not impossible. After all, war can be fun in a weird, druggy kind of way. 2008’s smash hit The Hurt Locker was after all based on Chris Hedges’ nonfiction book War Is A Force That Gives Us Meaning – a precise demonstration of what makes war addictive, attractive and cathartic for its participants. But what Winston Churchill called the exhilaration of “being shot at without result” is mixed with so much terror and loss. At very least, war games need something like Cart Life with guns – Tank Life, perhaps.

Maybe war and games were never meant to be. At very least, their harmonious co-existence is not a foregone conclusion. Most of the things which conventional game design has taught us to value and work towards are antithetical either to telling the truth about war or to criticising it politically. Maybe developers should try giving the relationship some space, and broaden their horizons.

How to Fix Assassin's Creed Unity PC Launch issue, Blue screen issue, Uplay Crash, DLL Error issue and more

How to Fix Assassin's Creed Unity PC Launch issue, Blue screen issue, Uplay Crash, DLL Error issue and more Witcher 3: Hearts of Stone - Without a Trace Quest Walkthrough

Witcher 3: Hearts of Stone - Without a Trace Quest Walkthrough How to Automate Microsoft Office Tasks with IFTTT Recipes

How to Automate Microsoft Office Tasks with IFTTT Recipes Dead Space 3 Wiki .

Dead Space 3 Wiki . Deleted a Google Calendar Event by Mistake? Here's How to Get It Back

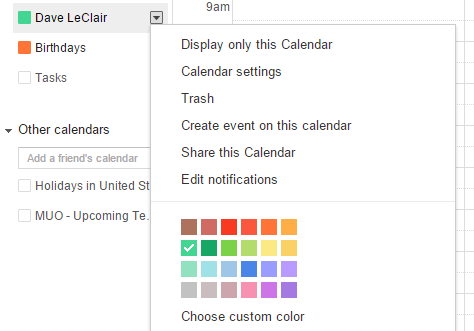

Deleted a Google Calendar Event by Mistake? Here's How to Get It Back