In the summer of 1998 it was to my sheer delight that I won a copy of Resident Evil 2 from a local radio station. By the time I had finished it, with prowess that has long since left me, I was able to trot a squeaky block of tofu swiftly from the sewer depths to the police department’s roof, equipped with only herbs and a knife. This was the distilled Resident Evil experience.

At its prime, the series stood as a fascinating demonstration of gameplay as systems of meaning. The whole survival horror genre is one of perhaps unique status in that narrative subtext is essential for the game to work in any way. I’ve written in the past about how games are best considered as elements working in collusion, and Resident Evil is a fantastic example of this - in accordance with the metric of tools plainly churning out ‘fun’, its system of mechanics could easily be surmised as quite terrible.

Of course, that would involve ignoring a significant portion of what made the old Resident Evil games so engaging. Rather, it’s better to think of gameplay as a language, whereupon RE’s mechanics would be prose centring on a tone of fear and desperation. It was, after all, this pivotal element that initially entered the series into hearts and minds, now long since abandoned.

Resident Evil Code Veronica, one of the last classic RE experiences prior to the recent shift to more action-orientated gameplay, is possibly my favourite entry in the series if only because it was dressed to the nines in the story’s iconic absurdity.

Departing from the familiar locales of the previous main entries, Code Veronica begins on a newly-besieged prison island owned by the evil Umbrella Corporation. The island is administrated by a shrill, schizophrenic and needlessly theatrical fop Alfred Ashford, who hounds the player for most of the game. Such is his preposterous villainy that one diary entry tells of his need to put to death some workers who built for him a secret bridge to a secret house, and that Alfred is expressly OK with killing them because he is a villain.

Code Veronica carries the Resident Evil legacy of hilariously bad cutscenes and voice acting, and yet the inadvertent campness does little to spoil the game’s overall suspenseful tone. As always, the series’ original gameplay conjures anxiety so successfully that it excels at picking up the narrative slack. While boasting many additions to the initial formula, Code Veronica retains a considerable portion of its predecessors’ idiosyncrasies, offering a variety of features to aid the player (e.g. auto-aiming and a handy about-turn) without compromising the game’s balance.

To an outside observer, the later change to a third-person shooter in Resident Evil 4 might seem like a natural continuation of the series’ increasing use of action-adventure elements. In spite of all the gearing up towards bombast, Code Veronica remains such a different experience to RE4 because at its core it plays like a strategy game (albeit of a vastly different type than Command and Conquer or Tactics Ogre). Let’s break the gameplay down to its major components to see how this is so.

If you’ve ever played an early Resident Evil game you’ll know what its gameplay amounts to. Movement is cumbersome and slow feeling, even at the player character’s fastest sprint. Many have likened it (not unfairly) to driving a tank as opposed to the human avatar on-screen. As mentioned, a quick about-turn is available for emergency retreats, which is especially useful when face-to-face with a giant green Steve monster.

This serves as the backbone of the game’s mechanical system. Navigation and exploration take up most of the player’s time and characterize the imminence of the other mechanics, namely combat and puzzles.

Combat in Code Veronica is archaic - the second-person viewpoint often obscures the player character’s directional facing, inhibiting the player from lining up shots with ease. Turning in the horizontal axis is sluggish, as with movement, while the vertical plane speaks of only three degrees. Without the autoaim function, shooting an enemy on the first try is a matter of planning or luck. Most importantly, you’re prevented from moving when aiming, while drawing and holstering any weapon involves a small time investment that can place you in danger in the abundant confined spaces.

Due to its deficiencies, combat is governed by the availability of ammunition and health items alongside the layout and variety of enemy monsters in each particular area. The scarcity of resources is balanced against the need to explore areas for essential keys and puzzle pieces, so the mindset the player must adopt is one of resource management with these as top priority. After this, monsters are to be avoided so as to preserve ammo, often at the expense of health items. On the other hand, if health items are running low, enemy herds may need trimming down or complete removal to facilitate ease of navigation.

The result is an ingrained fight or flight mentality as the player needs to be constantly aware of his/her inventory, given its incredibly limited capacity. Occasional storage crates serve as a dumping ground for collected items, freeing up inventory space and allowing the player to restock on reserves.

Puzzles, meanwhile, mainly feature either as locked doors or a multitude of minigames. The latter serves both to prevent the flow of combat/exploration from getting tedious and to offer the player a bit of pensive respite. It’s no accident then that these quieter moments often end with a crash as monsters flood the scene.

Areas themselves are turned into large-scale puzzles based around the piecing together of which key opens what door and what item is used where. Locked door puzzles often involve the player backtracking over familiar grounds, necessitating navigation of safe or unsafe areas and finding optimum routes to match the player’s needs and resources. Having to pass again through a causeway populated by bandersnatches can be risky and intimidating – it may be best to retread that path as seldom as possible.

Taken all together, the necessity for exploration is impeded by the presence and variety of monsters. Enemies, in turn, can be avoided or combated in accordance with whatever assets are available and the difficulty of navigation. Puzzles are completed to avail of more resources or to open new areas for progression. Exploration and backtracking demands inventory management as the player must juggle items and available space in anticipation of the coming need. Each mechanic interacts with the others, forming a very fulfilling and cohesive system.

The overall effect is to set you on edge by inhibiting your command of the situation. Through restrictive combat mechanics and an emphasis on resource management, enemy encounters are framed as situational problems rather than opportunities.

Unlike RE4 and Operation Raccoon City, where emphasis of combat is on player accuracy, gunplay in Code Veronica asks little by way of player skill. In the more action-inclined games, enjoyment is largely derived from well-placed shots and successful melee attacks. Meanwhile, gratification in Code Veronica is achieved by clearing a room with as little impact on your ammunition stock as possible or by safely weaving in and out of a zombie crowd. Combat is a means to an end.

Evasion of enemies and player survival is therefore achieved through an enactment of strategy – resource management, fight or flight decisions, efficient navigation of maps – all of which are heavily tied in to one another. Interpretation of these mechanics is helped by an aesthetic framing of the virtual world and player abilities (or inabilities) that ingrains player technique as strategic. Switching the camera to a more accommodating perspective would devastate the player’s visual powerlessness, for instance, and render the combat mechanics’ shortcomings far more harmful than is presently the case.

Similarly, an abundance of ammo and health items would strip exploration of all its danger since damage and combat no longer really threaten player progress. Gameplay and aesthetic both direct the player into a particular mindset to establish atmosphere and it is this quality that makes a game survival horror.

Take for example some of the most memorable segments in the RE franchise – those involving Nemesis and Tyrant-103. Against these indomitable forces, the player is forced to flee or expend vast resources in fighting the creatures. Similarly themed segments can be found to various degrees in Clock Tower and Dead Space, as well as in Operation Raccoon City, the original Tomb Raider and Arkham Asylum.

But whereas Birkin, the T-Rex and Killer Croc certainly fit the criteria of placing the player on the back foot, these are nary but novelties in the context of each game’s totality. On the other hand, Dead Space and Clock Tower are structurally designed to elicit such fear all day long (with exceptions, of course - even Resident Evil ends with a rocket launcher).

The first Dead Space employs similar gunplay mechanics to ORC and Uncharted, emphasising combat ability and accuracy as player aptitudes. So too, ultimately, does Project Zero (aka Fatal Frame) wherein the player navigates a haunted house in much the same way as Resident Evil, but relies on first-person perspective combat to photograph and defeat ghosts.

When faced with a mob of necromorphs in Dead Space, however, the player is asked to focus attacks on staving off the hoard while identifying priority threats. Targeting specific limbs and employing stasis and kinesis shapes the tactics by which this goal is achieved. Project Zero grants the player significantly increased damage output by telling him/her to get in close, build up power by keeping the ghost in frame and take the shot at the last possible second. Both Project Zero and Dead Space diverge from their mechanical ilk through a casting of the protagonists as seemingly unequal to the forces against them and encouraging a reliance on strategy to overcome these far more powerful foes.

So although Dead Space and ORC share a mostly similar core mechanic, the gameplay difference lies in the systems’ differing tendencies of narrative. Likewise, Clock Tower and Code Veronica both invoke strategic thinking through their gameplay despite featuring vastly different mechanics. Though the units in each system differ dramatically, the quality that makes each of them so characteristic and so alike takes form when considered teleologically, with the player’s understanding as a final goal.

As with all games, our experience is governed by our ability to interpret the system in place as a bundle of meanings, rather than simply as an available array of actions. Navigation, combat and puzzles in Code Veronica are not three distinctly isolated realms of player activity. Nor are they, as mechanics, removed from the game’s narrative function, contrary to the common nattering of gameplay and narrative being at odds with one another. Only through understanding it in terms of narrative subtext, even subconsciously, is the system at all functional and intelligible.

It’s because tone is utterly essential in survival horrors that the genre is exemplary of videogames as inherently narrativistic experiences. Survival horror demands a game be regarded holistically, as a collection of meaningful systems built towards one unified purpose. Heads generally nod at the analogy of game mechanics and motifs to grammar, yet these same noggins often rally against its extension to systems and language. Nevertheless, even though a game may be delightfully camp and preposterous, it can still make for a terrifying experience on the tonal grounds of gameplay alone.

How to Unlock Moo-rderer Achievement in The Witcher 3 DLC Hearts of Stone

How to Unlock Moo-rderer Achievement in The Witcher 3 DLC Hearts of Stone Official Fix For Nasty PS4 Disc Eject Issue Released By Sony

Official Fix For Nasty PS4 Disc Eject Issue Released By Sony Life is Strange Episode 3 - All 10 Optional Photo Locations

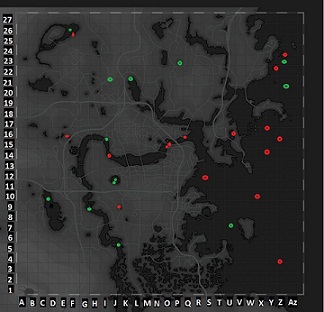

Life is Strange Episode 3 - All 10 Optional Photo Locations Fallout 4: Underwater Secrets / treasures map - tips

Fallout 4: Underwater Secrets / treasures map - tips Dying Light (PC) review

Dying Light (PC) review