Strong women in video games have always been something of a Pandora’s Box—we know they exist, most of us want them to exist, but the second they reveal themselves, everything sort of goes to hell. It isn’t that some of us (again, I like to think most of us) don’t gratefully accept these women, but the aesthetic qualities of female characters don’t always seem to balance well with their intended depth.

More often than not, the idea of “women” in games has been simplified due to character designs that favor beauty, or sexuality, over practicality and ability. And, while not all titles have played into this stereotype, it’s prevalent enough to have done some damage to the way we generally perceive heroines.

Thankfully, this year, we were given a number of intelligent, willful, confident and, perhaps most important, fallibly human heroines in the forms of Naughty Dog’s Ellie, Irrational Games’ Elizabeth, Square Enix’s reboot of Lara Craft, and Quantic Dream’s Jodie Holmes. While the latter title, Beyond: Two Souls, has been met with wildly mixed responses, the former three titles—The Last of Us, BioShock: Infinite, and Tomb Raider—elicited a largely positive consensus.

Their heroines, however, did not.

Somehow, in spite of their complex character development and fantastic voice acting, people offered mixed responses to these strong heroines. Some found them annoying, likening Ellie and Elizabeth, at least, to feeble (game-breaking) damsels like Ashley from Resident Evil 4. Others—such as myself—were intrigued by what the realization of these four women brought to their respective games.

Obviously Lara Croft and Jodie Holmes were vital to their titles, what with being the main characters and all, but the situation for Ellie and Elizabeth is a bit more unique and requires further consideration.

I'll be frank in saying that I think Ellie and Elizabeth are vivid characters that contribute wholly to the success of The Last of Us and BioShock: Infinite. I'll even admit, though this is a seemingly controversial position to hold, that I believe these titles belong to their heroines as opposed to their male counterparts (and don’t get me wrong: I love Joel and Booker and all their creepy, complicated, and misguided dad love).

But The Last of Us and BioShock: Infinite hinge on the success of their secondary characters and the player’s ability to empathize with their particular struggles.

So, what makes these women so engaging?

Well, for starters, they’re not overly sexualized to the point of being nothing more than objects. Yes, they’re attractive (this is a staple the gaming industry is not likely to move away from for quite some time) and, yes, Elizabeth’s dress isn’t completely modest. And, yes, Ellie is subjected to some mistreatment at the hands of men in a stirring section of the game that reinforces both the power and fragility a well-crafted character can display.

But the success of these characters isn’t dependent on their physical attributes.

Elizabeth proves intriguing due to her mysterious abilities, touching naivety, and alarming transformation in the ending cinematic (I’ll leave it at that—though, shame on you if you haven’t yet beaten the game).

And Ellie? Well, she’s just so incredibly spunky and real and raw. Her character development is some of the best I’ve seen in recent years, allowing the player to experience her in complex and interesting roles: from bratty, misunderstood teenage tag-along to inquisitive young woman to provider, victim, and attempted altruist.

Ellie runs the gamut in terms of personas. She evolves, annoys, provides witty commentary and companionship and questions Joel’s decisions in the way that any player (with a conscience) would. In my opinion, any character that makes you question humanity and your own actions is a testament to the art of game design.

And, that's all good, but what's particularly new about these things?

I'd argue not much. There have long been strong and weak heroes and heroines in gaming. We've seen, played, judged, liked, criticized them all in the past.

After all, there's that old adage of there being nothing new under the sun—and that adage proves correct, even under virtual suns.

Don’t get wrong, though: while there’s nothing completely new about the four characters discussed previously, this makes them no less wonderful, no less relatable, no less powerful in regards to bolstering women’s place in gaming.

They’re role models, certainly, but they don’t reinvent the concept of a strong heroine (functioning either as a lead or ancillary character). The designers of these females simply take the best elements of previously successful heroines and broaden these traits, using the new graphical capabilities to play on our emotions more so than to impress us with how beautiful/sexy/insert-flattering-yet-mildly-demeaning-adjective-here Elizabeth, Ellie, Jodie, and Lara are.

And this—this re-envisioning of the past—is a good thing. A good thing that we need to be more conscious of in playing new games and celebrating the old ones.

Don’t believe me when I say that strong women in video games are nothing new?

Well, let me break it down for you: I started gaming in the early to mid-90s, and there were strong women even then. I know this because I looked for them, unconsciously, as we all look for people with which to relate to and find strength in.

And find them I did in the forms of Metroid’s Samus Aran, Beyond Good and Evil’s Jade, Final Fantasy VI’s Terra and Celes, and Breath of Fire’s Nina. This is obviously just a cursory list—as, even now, I could ramble off an additional dozen or so names—but I think it parallels well with the current generation heroines mentioned earlier.

For example, Samus Aran and Jade are obvious picks in regards to influential heroines. They’re women who led their specific titles to success (albeit in varying degrees) as protagonists.

Both Samus and Jade accomplished this in ways that were not solely dependent on their sexuality. These heroines displayed a sense of duty and determination in a way that was not tethered to their sexuality.

Put simply, these women weren’t “strong for women,” they were simply strong. Simply likeable. Simply progressive.

In the same vein, neither Samus nor Jade relied on their bodies or beauty to appeal to the player. One of the first female protagonists in video games, Samus wasn’t even revealed to be a woman until the very end of Metroid. Due to the bulky, yet practical, power suit and an androgynous name, the player had already built a relationship with (by embodying) Samus prior to “unmasking” or, as the case may be, “unsuiting” her.

Jade was much the same, though obviously identifiable as a woman from the beginning. She functioned as a tomboy who favored practical clothing, martial arts, and investigative journalism. Honestly, what more could you ask of a role model for impressionable young women as well as a model for the design of future female protagonists?

As with Lara and Jodie, Samus and Jade were embodied by the player and thus served as the lens for the action that took place in Metroid and Beyond Good and Evil. Celes, Terra, and Nina were not—at least, not always.

In a move that seemed radical to me as a child, Final Fantasy VI and Breath of Fire III (as well as Breath of Fire IV and Dragon Quarter) established a protagonist while also allowing the player direct control over a number of other characters during certain portions of the game.

Celes, Terra, and Nina were all playable at points in their respective titles and, because of this, were developed in ways similar to Ellie, who was also playable for a controlled amount of time, and Elizabeth who, while unplayable, aided and accompanied Booker throughout a large portion of BioShock: Infinite.

Nina—specifically the Nina from Breath of Fire III—is arguably the most direct precursor for a character like Ellie, considering both games encompassed an extended span of time (several years in Breath of Fire III, approximately a year in The Last of Us) and allowed the player to see notable changes and developments in their heroines.

Both Nina and Ellie grow up over their journeys, in part due to the natural passage of time and in part due to the situations and responsibilities thrust upon them. They’re both presented as young and a little bit reckless, but they’re both appealing in spite of these qualities that could be annoying if handled incorrectly.

Celes and Terra don’t parallel Elizabeth exactly; it’s rather hard to locate an exact parallel for Elizabeth, in fact, because she’s one of few escort characters done well. However, they resemble Elizabeth in the fact that their histories are complicated and the transformations they underwent between the beginning and the end of Final Fantasy VI are, at least in the case of Terra, arguably as bizarre as Elizabeth’s own transformation.

Similarly, as with Elizabeth, there is still some debate over whether Terra effectively eclipses Locke and takes the role of protagonist for herself. This is, perhaps, an easier argument to make than in the case of Elizabeth, who is never directly controlled by the player, but it bears mentioning.

As with Elizabeth, Celes and Terra were both held against their will and exploited in Final Fantasy VI. Locke and other characters often worked or contributed directly to saving both of them; however, despite being “victims” in the strictest sense of the word, they never came off a “victimized” or outright defeated.

Instead, to borrow language used in the beginning of this article, they appeared as intelligent, willful, confident and, perhaps most important, fallibly human (well, sort of human in the case of Terra) heroines.

These are all important traits, but they’re nothing new. More often than not, the making of a strong female protagonist relies on a willingness to look back on what was previously successful instead of relying on the aesthetic qualities technology affords a particular character.

And, as detailed graphics become more and more commonplace, it will hopefully become easier to look past them for the influential and positive traits that our most beloved pixelated, polygon-shaped heroines readily displayed.

After all, innovation should improve—not detract from—our ability to experience fully realized stories and characters. Even if those stories are female-driven and those characters are heroines, not heroes.

DJ Mustard to release new remix of Rihannas FourFiveSeconds

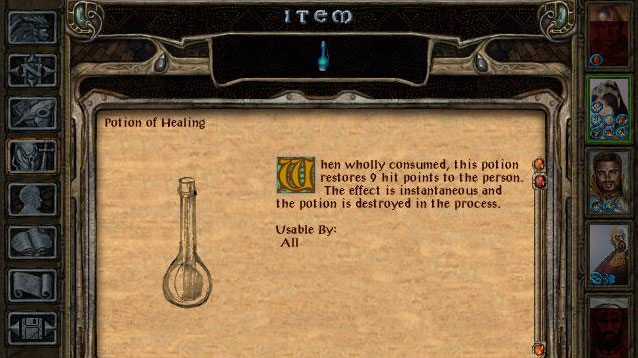

DJ Mustard to release new remix of Rihannas FourFiveSeconds List of Unlockables in Dragon Age Legends for Dragon Age II

List of Unlockables in Dragon Age Legends for Dragon Age II How to get Destiny Exotic items, Engrams, Weapons, Vanguard Armory and more Talking to The Tower NPCs

How to get Destiny Exotic items, Engrams, Weapons, Vanguard Armory and more Talking to The Tower NPCs Destiny Queen's Wrath Event Guide

Destiny Queen's Wrath Event Guide Glitch Allows You To Get Unlimited Items From Chem Cooler In Fallout 4

Glitch Allows You To Get Unlimited Items From Chem Cooler In Fallout 4