Next year the Rainbow Six series turns 17 with the upcoming release of Siege, and besides making me feel old, it’s made me feel apprehensive.

Rainbow Six originally came to life as a concept for an FBI Hostage Rescue Team simulator by the newly formed Red Storm Entertainment back in 1996. While it later went through several different iterations during the design process, the focus on realism, decisive action and a vulnerability to the combat remained: one bullet will take pretty much anyone out of the fight, friend or foe.

When the game finally launched in 1998 it went up against strong competition from Half Life, Unreal and Tribes. While each of these games went on to spawn their own franchises, their approach to violence was gratuitous. MIT graduates fired rocket launchers at aliens as men with jetpacks rained death from above while capturing flags.

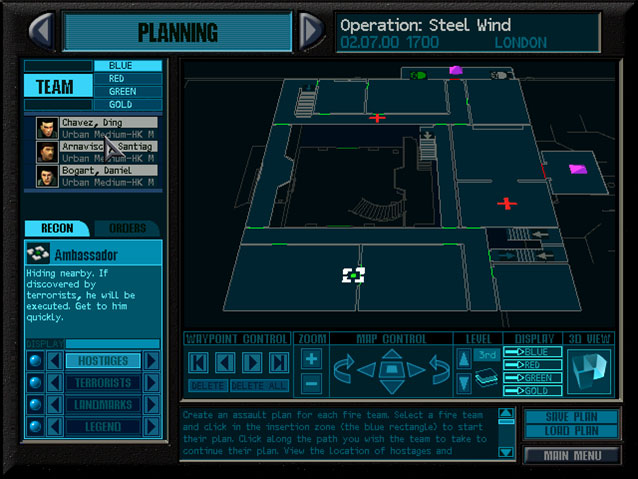

Rainbow Six was more about professionals performing a dangerous job. The solid theme holding together the design is that confrontation is dangerous and unpredictable. You’re given a mass of information for every mission in the game, the final say over your troopers equipment and the route that your AI squadmates are going to take. You have complete control of every aspect of the game except for combat.

This teaches you to fear firefights. When one of your soldiers is taken out he’s dead for good, and as you only have a finite pool of Rainbow Six operatives to choose from every death makes those later levels that much harder.

The end result is that in an effort to control these engagements, you spend a lot of time looking at the planning screen and jumping in and out of missions trying to control this violence in an effort to come out unscathed. Unlike the similar Swat 3 released in 1999, there was no non-lethal approach.

You quickly learn to respect this violence and you don’t really climb the difficulty curve, you just get better at managing your engagements so that you have a substantial advantage every time you pull the trigger.

It’s a unique feeling and one that’s only re-enforced by the negative outcomes to your opening firefights as you learn the rules.

The game was popular enough to receive a sequel in 1999, Rogue Spear. The game was similar in theme, being built on the same engine and sharing the attitude to violence. The two games were received well enough for Ubisoft to swing in and pick up the studio in 2000, before putting together two other Tom Clancy properties that had a similar level of respect for conflict: Ghost Recon and Splinter Cell.

Ghost Recon was much more of a standard shooter. While a quick burst of automatic fire would take care of any threats you might encounter, there was no planning stage. Orders were given instead through a “command” map available in play, so you could adapt your tactics on the fly. It’s harder to talk about an economy to violence when one of your soldiers can carry an M249 SAW, but the series still maintained a similar level of dread whenever you had to pull the trigger.

It’d be nice to be able to point the finger at Ubisoft for the Tom Clancy brand declining into homogeneity, but they brought us the finest Rainbow Six so far. Rainbow Six 3 gave us the top down command map from Ghost Recon so that you had in-mission control in addition to really beefing up the planning stages.Violence was still something to be feared, although it was a little slicker and easier to hand out now.

Then the magic vanished.

2005’s Rainbow Six: Lockdown did away with the planning phases and made the maps more linear. Rather than coming at a problem in a way that made you most comfortable, you have to push your way through the set pieces put in place by the game. Invariably, as was the trend with games at the time this meant you were putting rounds into quite a few faceless grunts.

This marked the start of what I like to refer to as the brands “consolification”, where the design on the three franchises was stripped down and retooled to a point where it wasn’t really recognisable. Splinter Cell went from hardcore stealth game to sneaky murder simulator with 2006’s Splinter Cell: Double Agent and Ghost Recon… well, Ghost Recon was actually still fairly reverent in its approach up until 2012’s Future Soldier.

I think it’s fine for games design in franchises to change over time, but this commodification of violence just felt so alien in a game where just a few years earlier it’d been such a chilling prospect as I ducked my way through corridors.

In 2006, 8 years from the original release, we were given Rainbow Six Vegas. I loved Vegas, but the design pointed more towards player empowerment than the unique feel that the franchise was famed for. You’re given a cover system, regenerating health and enemies charge around armed with machine guns and riot shields as you tear up casinos under withering gunfire while bonuses and score gains pop up in front of you. Your teammates may fall under a hail of gunfire but can be easily revived with no ill effects. Conflict is no longer scary, it’s mandatory. You’re the shining god of pew-pew land, and nothing short of several magazines of assault rifle ammo is going to stop you.

Again, it’s not that I think it’s a bad game, I’m just disappointed. The best way to take a look at these is to watch these two short clips of breaches below:

Ghost Recon: Future Soldier (2012):

Rainbow Six (1998):

Flashy gadgets have replaced intelligent play, and that makes me a little bit sad to the point where I’ve started to pay less attention and I’m picking the games up much later, if at all.

When I started to see footage for Rainbow Six: Siege I started to get that old buzz back. It’s impossible to really see how a game will play from a choreographed press event, but it looks like it could be a return to form.

Emergent multiplayer gameplay seems to be replacing the flashy set pieces that’ve been plaguing the series, and while the firefights still seem a bit actiony for my tastes I’m nervously excited. The idea of breaching the floor or blasting through a door to surprise enemies is impressive, it’s a good example of new technology being used to enhance older concepts.

The staged scenes of people dashing around between floors and tactical choices being made on the fly look fantastic if you can get a strong community to form around it.

Luckily, Rainbow Six has always had a strong community around it, which has withered away slightly as the games have offered less of a unique experience. Can Siege recapture these older fans? That depends on the answer to the big question: Is Siege afraid of it’s violence, or does it revel in it?

Tom Clancys Splinter Cell: Conviction Guide

Tom Clancys Splinter Cell: Conviction Guide A First Look at The Elder Scrolls Online

A First Look at The Elder Scrolls Online Metal Gear Solid V: TPP Guide - How to Get GMP Easily

Metal Gear Solid V: TPP Guide - How to Get GMP Easily 4 Nintendo Products That Were Way Ahead Of Their Time

4 Nintendo Products That Were Way Ahead Of Their Time Metro: Last Light – Faction Pack DLC Walkthrough

Metro: Last Light – Faction Pack DLC Walkthrough