Dark Souls 2 is out on PC today. Praise the sun, etc, etc. Our review is coming later on, for the PR agency has yet to furnish us with code. So instead I'm going to have a quick rant about lighting engines, PC ports, preview footage and gamer expectation.

As you probably know by now, the PC version of Dark Souls 2 is one of the best games ever, made better. Frame rates and resolutions are naturally improved, and on the whole it's that little bit more impressive than it already was. If you have a PC that'll run it, some money, and too much time on your hands, then get out there and buy it.

It's a great game. It is, however, nowhere near as impressive as it could, and to some people, should have been. I'm referring to the now-infamous lighting engine that never actually made it to the final code. Upon the console release, some tut-tutted at the downgrade, hoping that the PC version would incorporate at least part of this fabled lighting.

Not so, of course. In fairness, the more level-headed members of the community thought this would never happen. But some did. Whether they expected the whole shebang or just a minor upgrade – and as deluded as they may well have been – their expectations are another case of publishers and developers baiting and switching players. It's not a new thing, and it'll keep on happening.

The reason? Because we're all in love with the idea that progression is equivalent to a bump in graphical fidelity. It's utterly natural and I'm as guilty as any other player of wanting better graphics (and art direction). To evolve is to change, someone once said (or maybe I imagined that). Either way the easiest indicator of evolution in gaming is better visuals.

Sadly, it's also putting unfathomable pressure on studios and publishers to make their games look better than ever before. Disappointment is inevitable. We've seen it in the past, with that Killzone 2 trailer. Madden and Need For Speed 'Target Visuals' were bandied about at the start of the last generation, looking impossibly good.

Yet people still believed we'd get there. No chance. No 360 Madden title hit those heights. Killzone 2 was a marvel of technology, but it wasn't the same as in the E3 2005 demo.

These aren't isolated incidents. Spectrum cassette boxes illustrated the games inside using superior images from rival machines. Bullshots are still utterly rife, captured at resolutions that would melt consoles. With E3 upon us and a new generation of consoles being pushed, we'll soon be gazing upon the next wave of trailers and other promotional material that seems too good to be true.

This is not surprising. Neither, really, is it that gamers still fall for this. The backlash against Watch Dogs is a recent example. 'It doesn't look nearly as good as the E3 2012 footage!' 'Downgrade confirmed!' Well, yes. Of course.

It's not just gamers that have unrealistic expectations, however. Many times it is the developers themselves with unreasonable or unattainable goals. I've sat in meetings where a global publisher with more money and manpower than the United States government has told of its plan to make its 360/PS3 open-world racer have the same scope as GTA and the same texture fidelity as Gears of War. We told them it wouldn't happen. It didn't.

Why make these bold claims if you can't back them up? Well, publishers want to sell their games, and will use every trick in the book to make it happen. But, just as importantly, developers are gamers. They want to make the game look as good as it can, run as well as it can. They're not Snidely Whiplash, cackling as they show one thing and then deliberately substituting it for another. But over the course of years, things change in development houses. Maps change. Player counts are reduced or inflated. Entire modes, characters, and mission sets are binned. You settle for standards you'd never have dreamt of at the start. There are many reasons for these shifts, but time and money are two of the key factors, as you'd expect.

There's an idea that, for certain movies, the trailer you see pre-release is representative of the film the studio wished they had actually made. In a lot of ways, the same is true for video games. E3 demos and the like represent the game the developer would ideally want to sell. What they end up with can sometimes be drastically different.

So, why do we still want to believe? Because we literally buy into it, by tribally backing consoles, sometimes early and almost always expensively. Because graphics equals progress, for better or worse, even though we know, in the back of our minds, that's not the whole story. Bullshots and unrealistic trailers will remain a fixture of PR campaigns until the graphical arms race finishes. Why? Because everybody, from developer to consumer, wants to believe.

Fallout 4: Wasteland Survival Guide

Fallout 4: Wasteland Survival Guide League of Legends (lol) - Tips and Tricks for Beginners

League of Legends (lol) - Tips and Tricks for Beginners Orcs Must Die - Review, Game Guide, Help, Tips & Walkthrough

Orcs Must Die - Review, Game Guide, Help, Tips & Walkthrough DreamHack Open Cluj-Napoca Format and Schedule

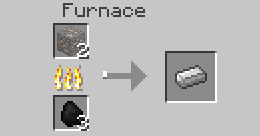

DreamHack Open Cluj-Napoca Format and Schedule How to make Iron Ingots in Minecraft on the PC

How to make Iron Ingots in Minecraft on the PC