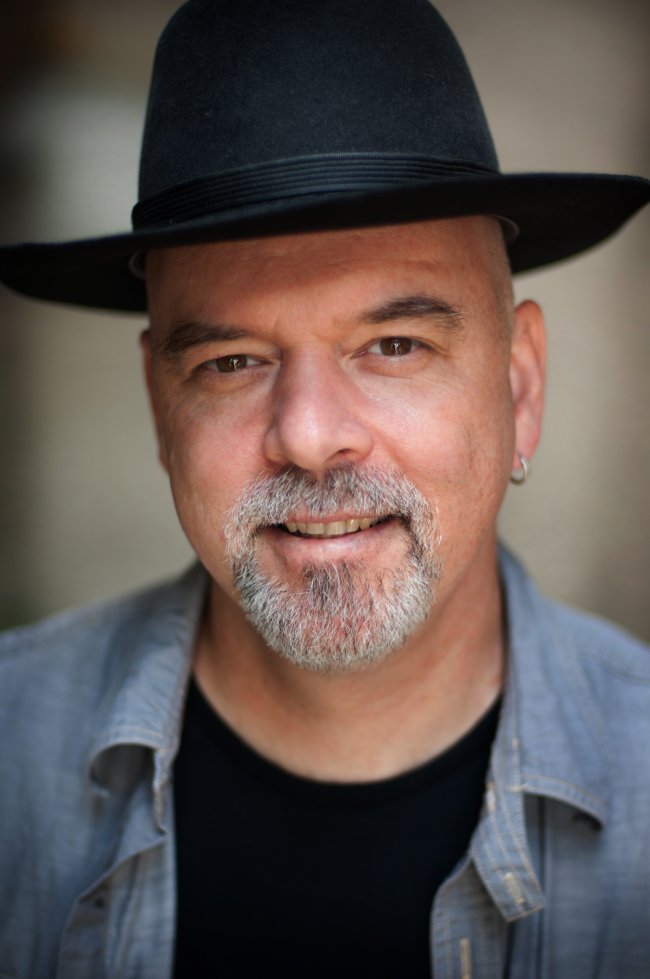

Peter McConnell is perhaps best known for his many contributions to soundtracks of classic LucasArts titles from Sam & Max, to numerous Star Wars titles, Day of the Tentacle, Full Throttle and The Dig. And of course, Grim Fandango, a game that's getting the remastered treatment later on this month.

Following his days at LucasArts he continued to work with Tim Schafer and Double Fine alongside other developers. He has worked on the soundtrack of Plants vs. Zombies: Garden Warfare, The Sly series and even Hearthstone. Apart from seeing his soundtrack for Grim Fandango re-recorded, the conclusion of Broken Age is coming up (hopefully this spring) and we thought we'd reach out to the prolific composer with some questions.

GR: What instruments or musical technology do you favour - is there a particular style that defines your work?

Peter McConnell: "I don't think my work is characterised by a particular style or instrumentation as much as it is by a certain whimsical attitude. I've written in many styles of music, for many kinds and configurations of instruments, from roots-y folk music to synth pop to full orchestral scores. I think the range of style comes from having lived in some very different places - Switzerland, Eastern Kentucky and Boston to name three - and absorbing the music around me. We live in a mash-up culture and I love that it's possible to express oneself musically without necessarily feeling constrained by style or genre. But whatever musical style I choose, I find the place where it resonates with me personally, and I try to convey both a love for the music and the story it scores, along with a bit of a sense of humor."

What's your approach to a video game project? Do you look to past genre works for inspiration, work with the development team on the game's central themes before penning anything?

"Every project is different, but in general I do like to work out the main theme melodies in advance and be sure that the project team feels good about a few important pieces before getting too far into the score. This goes back to working on titles like Grim Fandango for LucasArts. Early on in that project, Tim Schafer gave me a bunch of cinematic and musical references to digest. Then I spent several months just humming and playing tunes into a hand-held recorder, then running them by Tim - long before I ever started to work in the studio. Now, years later, I've been lucky enough to revisit that score for the new re-mastered version on PS4/Vita, re-mixing and adding tracks to some pieces and completely re-recording others with live orchestra. I have to say I'm glad I took extra care on the themes because I feel they were really able to blossom in the new live recordings."

"Beyond getting a good head start, it's important to know when a particular part of the game is ready to score. If you start too soon, that part of the game may change so much that you have to throw out what you did. If you start too late, you get a schedule crunch. It's a dance that you do as a composer, based on your knowledge of game production and what inspires you to do your best work."

How do you think gaming music has altered over the years? Has there been clear seismic changes (adoption of better audio tech, push to full symphonies etc)?

"When I started we still wrote for MIDI music AdLib cards and the PC speaker, and a nice sample-based card was a luxury only a small part of the audience would have. The watershed moment came in the early nineties when games like LucasArts' Rebel Assault first started to stream digital audio. That meant you could record live music and put it in a game. All of the major changes since then - the big budgets, live orchestras, name-brand bands and Hollywood composers - all were a logical consequence of that one breakthrough."

Given the industry's soundscapes were birthed in chip tunes and have evolved over the past thirty years, does that give the medium a greater diversification of signature styles than say, the likes of Hollywood?

"Yes and no. Technological constraints have sometimes fostered creativity in game music, necessity being the mother of invention, and I like to think that some of the early LucasArts scores are an example of that, not to mention truly iconic music like Super Mario or Legend of Zelda. But there has also been a tendency to follow certain trends and, to some degree, to imitate Hollywood. And vice versa - sometimes I think game music affects Hollywood scores more than the other way around. It's an open question whether games or movies have done more knock-offs of Carmina Burana. The bottom line is there is tremendous variety, but also a tendency to conform to fads, in both games and Hollywood."

Where and when do you work best?

"Under pressure, with a talented team. Two recent titles that come to mind are Double Fine's Broken Age and EA/PopCap's Plants vs. Zombies: Garden Warfare. Two very different scores, both composed in my studio in collaboration with folks who care about how to make music really speak in a game, and are willing to try all kinds of experiments to make it work just right. With Broken Age I have also been able to work with some wonderful live musicians, including the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and it took a lot of dedication from a lot of people to make that happen. With PVZG, we were able to do some really genre-bending pieces just because they worked. Who ever heard of composing for zombie choir? I love that kind of thing!"

One question, two different angles. What's been your favourite piece of music to work on (and why), and secondly, what would you rate as your all time favourite piece of gaming music (that you weren't personally involved in)?

"Picking favorites isn't easy, and the answer changes almost from day to day. I like to compose music that I know will be played by great players, but then again I also like being a one-man band. An example of the best of both worlds would be ‘Lamprey Attack' from Brutal Legend: I got to play some really aggressive guitar parts, then get a world-class Metal player to do the solos, and record the orchestra at Skywalker Ranch. More recently with Hearthstone: Heroes of Warcraft, I played a kind of acoustic guitar solo suite, then turn it into a full-on band by adding tracks done by some wonderful wind players. In some sense my favorite piece is the one I happen to be working on at any given time, because I'm having fun doing it. And if I'm not having fun, I change the piece so that I am having fun! Composing for me is being entirely invested in the moment of making the music happen. And in answer to the second question, my all-time favorite piece of game music that isn't mine is still Michael Land's original theme from Monkey Island."

What's been the best combination of music and visual (or gameplay) in your opinion?

"That changes for me pretty much every year, too. I think the things I've seen recently from Starcraft II and Destiny are pretty amazing. Going back over time, I have to say that Grim Fandango is a special kind of game for me musically, almost like an opera. I was very fortunate to be able to score that kind of a title."

What do you think about the work Tommy Tallarico has done in promoting video game music through the VGL series?

"I owe Tommy a huge debt of gratitude, as I believe all of us game composers do. He has done more to raise the profile and quality of music and audio in general in the industry than any other single person. I think his biggest gift to us all has been to promote the history and culture of games and game music, reminding us that we don't just have today's hits, but are also building on a legacy, like film or television or other story-based art forms. Video Games Live is a very popular manifestation of that gift. He is one of the best entertainers I know, and we're all lucky to have him bringing our music to life on the big stage all over the world."

Is the acceptance of video game music a non-issue, given its celebrated by industry fans and performed live anyway? Or do you personally find it a stereotype to overcome in wider media and social circles?

"Every kind of music potentially has a stereotype to overcome; it just depends on whom you are talking to about it. I personally get a kick out of telling people that I write music for games. Of course you run into an attitude sometimes, but not nearly as much as was once the case."

Gaming music has been championed to be brought into the Classic FM Hall of Fame for many years - is this the right place for it to be celebrated?

"Given how much of game music is now orchestral, it's a reasonable place to be celebrated. Of course this leaves huge swaths of game music out, but that would be true of movie scores as well, which have all kinds of genres but get some recognition in classical circles. Speaking as a rock n' roll refugee from an elite music department where some students used to joke (mostly unfairly) that "music is to be seen and not heard," I think it's great that "serious" music fans are being exposed to game scores. Maybe the Rock n' Roll Hall of Fame could be as forward-thinking."

Old argument: the less tech game composers had to work with meant they had to get more inventive, and as such bred more iconic themes. True? Or is it same problem, just a bigger tool set?

"You could make the argument that production values have diluted the quality of many music genres, that memorability has been sacrificed to Immediate Impressiveness in just about everything in our culture. And you might even be right, but not in all cases. The trick is not to use the newer, more extensive resources as a crutch. I honestly think I'm doing my best work now, and I think that's true of most of my colleagues. I doubt Brahms complained about being able to work with bigger orchestras than Mozart. And while I love the old game tunes as much as anyone, I'm not in any hurry to write for an FM chip again."

Do you have an admired composer in the industry today?

"Three: Austin Wintory, Jason Hayes and Steve Kirk."

Video Games Live set the standard, but with the likes of the Final Fantasy and Zelda concerts, live shows of video game music seem to be gaining traction. Have you noticed a shift in perception and acceptance of gaming music?

"Yes, absolutely. And I only expect that to grow over time. I recently did a suite of music from Grim Fandango for performance by the Queensland Symphony Orchestra, and I'm looking forward to doing more concert music in the near future. I'm seeing that a number of symphonies all over the world are doing concerts of game music, so that has to say something about people's acceptance of it."

Secondly, what next steps do you think need to be taken to expand the accessibility and growth of the music scene?

"Just keep improving the quality and variety of the music. That will make all the other hard work it takes to promote and sell it continue to be worth the trouble and effort. Making more great games doesn't hurt either."

<b>Has digital marketplaces such as iTunes and Amazon opened the doors to producing and releasing game soundtracks at retail as a viable business?

"Absolutely. From my humble perspective it's a sea change. It seems to me that soundtracks used to be a niche market thing that didn't make much money at all - just barely justifying, from a business point of view, the cost to create, manufacture and get into the hands of fans. But I get the sense that digital downloads have changed everything, reaching enough people that physical soundtracks have benefitted as well. Digital downloads have let people experience their favorite soundtracks anywhere and everywhere, just as downloadable games have allowed people to experience interactive entertainment almost everywhere. Soundtracks are viable because digital entertainment is now ubiquitous."