The Marvel Cinematic Universe is starting to become as vast, daunting and bloated as the various comic books on which they’re based. A slate of films planned up until 2019, four ongoing TV series with more on the way, the wonderful daftness of comic tie-ins to the film versions of comics. It’s big, it’s multi-faceted, and somehow it’s... mostly really very good.

Jessica Jones, the second of five (FIVE) planned Netflix titles which focus on the superhuman denizens of Hell’s Kitchen in New York, a sort of grotty little lower-deck of the HMS MCU, slides comfortably into the precedent set by February’s Daredevil – set around the corner, and sporting a similarly manky colour pallet, but altogether bolder and with perhaps a stronger, more overriding identity than the flagship show – although this may be an issue for some, but more on that later.

There are so many alternative twists on superhero tropes that twisted tropes are some of the tropiest tropes, but Jessica Jones goes as far as to treat the very idea of comic-book heroism with contempt. Matt Murdock worked hard to become Daredevil, but a few streets away Jessica Jones, super strong and capable of leaping tall buildings with the best of them, nonchalantly admits in voiceover to contentedly making a living out of ruining marriages as a private investigator. Before smashing a client’s head through a glass door.

Captain America would blush (when he’s not, y’know, twatting dozens to death with a frisbee).

Indeed, it’s difficult to watch Jessica Jones while keeping in mind that it is occurring in the same world as the Cap. Tonally, the films and traditional model TV shows that form the bulk of the MCU are extremely similar. The same joyful, technicolor wisecracking in the face of existential peril.

The Avengers, Guardians, Agents of Shield? They aren’t stupid*, and they’re full of stuff you can be all whisky-tastingly academic about like “themes” and “character arcs” and “shit”, and being more accessible, more traditionally schlocky than what the Netflix shows offer doesn’t make them less good, but the quantum differential between Iron Man struggling with PTSD and Jessica Jones carving out a life in New York’s answer to Croydon, if Croydon itself was carved with claw hammers out of cement-hardened excrement, is so enormous that accepting them as being linked, even tenuously, might just be too much to ask.

Which is why, sensibly, they don’t go on about it. Allusions are made of course, but what’s perhaps most admirable about the Netflix titles is how unapologetically Not The Avengers they are. Having said that, the extremes to which it goes to be Its Own Thing are a little puzzling; both Daredevil and Jessica Jones have snaking plot arcs that involve vigilantism, cops, and big ugly law firms – fertile ground for knowing winks and nods – but it seems almost farcical that both stories are happening concurrently, involving the same classes of people, on the same streets, with nary a mention but one minor crossover late in the day.

It’s arguable that they’ve done well to avoid gratuitous fanwanking, but there is a case to be made for verisimilitude trumping the need to steer clear of continuity porn. Stuff gets blown up in Daredevil. A lot of stuff. Jessica would have heard it, though there would have been more pressing things on her mind.

Fundamentally, Jessica Jones is about loss. The loss of loved ones, the loss of dignity, the loss of control over one’s actions. Essentially, she is an abuse survivor, and we meet her as she struggles to rebuild herself after escaping her tormentor Kilgrave, played by nice guy David Tennant as a sort of evil twin of the Doctor Who incarnation which made him a household name (the parallels here could justify a wanky thinkpiece all by themselves – for a start, his evil power is a telepathic ability to make innocent people do horrible things for him).

Her tale of reclaiming herself in the wake of his devastation is thoughtfully presented and supported by all aspects of the production. The cinematography veers between function and cleverness – early episodes are littered with shots which use foreground objects to frame her, putting her in little boxes, separating her from the rest of the space in a visual echo of how she chooses to cope with trauma. Small, almost insignificant things, like her front door getting broken right in the opening shot, serve to give this almost indestructible PI a lingering sense of vulnerability. The door becomes a symbol of her recklessness, her weaknesses, and you find yourself worrying about it, those worries parroted by the supporting cast. Emotionally, it’s a masterful manipulation of the fundamental craving for safety which we all have.

Although, it’s not quite as masterful as it thinks it is. In technical terms, much of its visuals are disappointingly pedestrian. Daredevil had a real signature look, but some shots in Jessica Jones could be lifted from any of the dozens of competently shot dramas it shares the Netflix homepage with. There’s an obsession with extreme depth-of-field, where it is sometimes used to great effect, but at other times – and often very obviously added to the shot in post – it jars, as though it’s trying so hard to look like good cinematography that it actually ceases to be so. In fairness, it’s only an obvious sticking point here because it’s sitting alongside the aforementioned Daredevil and the likes of House of Cards, which is beautifully and deftly composed to a degree that suggests a budget far in excess of the not insubstantial one it already has.

Jessica Jones’ allegories can be a little on the nose too. It makes brain-boilingly obvious parallels between mind control and drug addiction, for example, but fails to explore them to an interesting place, as if the show might as well have stopped half way through and said “by the way, this contemporary thing is a bit like that mad thing, it’s evocative, yeah?”

So it’s smart, if not wholly polished, and it’s a million miles away from Hulk Smash, despite occurring just a few zip codes away from where Hulk smashed. This is a Marvel offshoot which humanises the superhuman in perhaps the most raw and attention-demanding way, and one which could only work as an addendum, nowhere near the centre stage. I like Black Widow, but I’ve never been worried for her. It’s difficult to imagine Jessica Jones: The Movie, or at least it’s difficult to imagine one without something like this series laying the groundwork.

When compared to Agents of Shield, the juggernaut traditional-model TV series which exists to fill in the gaps between Marvel movie releases, the strengths and weaknesses of both are pulled into full focus. Jessica Jones (and Daredevil) could never have the means to replicate the retina-bursting extravagance of The Avengers that AoS manages to pull off on a generous-for-tv budget, but it can be contemplative and clever where SHIELD break down doors and shoot aliens. It can tell the deeply personal stories of a small core cast, where SHIELD must divide its 45 minutes per week between a monstrous and ever growing ensemble of action heroes.

One approach is not fundamentally better than the other, and though the spectre of franchise fatigue is beginning to darken live-action Marvel’s horizons (the eye-rolling on Twitter when they announced phase three could have melted phones), that it has expanded to such a degree that it can accommodate this kind of project is a great thing. Jessica Jones cannot exist without the wider context, without the daft spandex shite-talkers and the Robert Downey Jr. vehicles that made it a marketing phenomenon. Had it tried, it would have spent five of its 13 episodes explaining how she can throw men twice her size through glass doors, and in doing so missed the bloody point. She works in a world where the exceptional has been normalised – a point the show itself makes, in the one and only instance which makes direct mention of its progenitors.

Jessica Jones exists in the periphery of the MCU, as it should, as it needs to. It’s completely unessential for those who aren’t bothered, or those who are too young, and utterly watchable without any prior knowledge beyond the general cultural saturation of the superhero myth. But as another strand of the wider mythos it has real power, as both an expansion of the Marvel universe and an addendum to it. Anchoring Iron Man’s gleaming hubris to something akin to the messy, complicated real world that we inhabit, and spotlighting that deeply rooted absurdity of superhero parables: that clown costumes are an antidote to misery.

It’s a counterpart to those things you’ve seen, then, but don't dismiss it as a footnote – it’s damn good.

*Alright, Agents of Shield is quite stupid

Tomodachi Life: Why Nintendo has to change

Tomodachi Life: Why Nintendo has to change Murdered Soul Suspect Scorned Case Guide

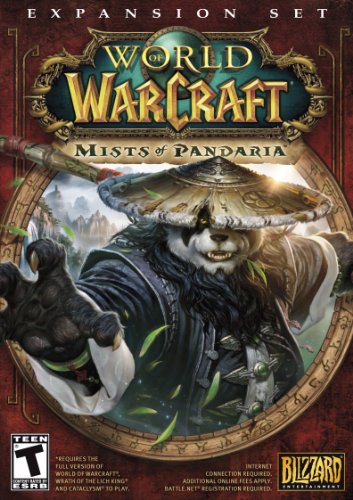

Murdered Soul Suspect Scorned Case Guide How to Make Gold Throughout a World of Warcraft Expansion

How to Make Gold Throughout a World of Warcraft Expansion Bioshock Infinite Guide: Kinetoscope Location guide

Bioshock Infinite Guide: Kinetoscope Location guide The mad nonsense of Star Wars Battlefronts Darth Vader

The mad nonsense of Star Wars Battlefronts Darth Vader