Tales of Zestiria's recent October release (January in Japan) marked the 20th anniversary for the long running franchise. It's received favorable reviews among fans of the series, and I couldn't agree more with that assessment. Sadly, Tales has never reached the same critical or commercial success here in the West as it does in the East. And that's a shame, because it has something I haven't often come across in many other games: a sense of adventure.

It's worth stating that these opinions are my own. What affects me may not do the same for you. Additionally, games that don't evoke a spirit of adventurism aren't instantly labeled as bad games. Baldur's Gate, Planescape: Torment, and Pillars of Eternity provided me with dozens upon dozens of engrossing hours. But they didn't leave me depressed when it was time to leave their worlds. It's a surprisingly rare feeling to experience; and knowing how the sausage is made (facts learned as we grow older) decreases the likelihood of its occurrence. So what are the prime ingredients for that unusual impression?

For starters, few things are more critical for an emotional investment in a game than properly developed characters. A believable or likeable cast can make journeys worthwhile in absence of other systems. This is something the Tales developers, along with studios such as BioWare and Naughty Dog, generally get right. The key to their success is making NPCs feel less like party members and more like friends and family, and it's all in the details. Time is spent on the finer points of their lives, exploring their deeper backgrounds, and evolving their personalities and connections beyond static reasons for them joining the protagonist. Garrus' and Shepard's long gestating friendship in the Mass Effect trilogy is a great example. Their warm conversation in the Citadel as they contemplated where they've been and where they've yet to go, all the while engaging in amusing horse play, was a lingering scene that reminded us how far they've traveled together. Better still, Mass Effect frequently showed companions interacting not just with Shepard but each other, earning their own romances or rivalries, giving them lives outside the player character's. The Persona series has built an entire mechanic around the formation of relationships, to great effect. The Last of Us showcased a surprising variety of animations and incredibly natural dialog between Ellie and Joel that rarely if ever repeated themselves. Those interactions and the effort involved in making them come alive made me care about polygonal people, and then sad that I couldn't spend time with them once credits rolled.

How characters say something can be just as influential as what they're saying, too. Tales of Zestiria's heroes speak in tones of excitement about the landscapes around them. They're eager to explore castles, ruins, and unknown lands, despite the dark threats looming on the horizon. As their sense of adventure grows, so does the player's. Hundreds of conversational "skits" also feature Sorey and company teasing, joking, and laughing amongst each other. Bleaker tones certainly have their place, of course, but the aforementioned sensations may be harder to evoke without moments of levity.

Well-established mythologies and histories play equally important roles in fomenting adventure. Video games allow us fantastical new realms to visit. Beautiful sights assault us unending. But beauty alone isn't always enough to form that special kind of magnetic pull for what's being rendered on screen. Offering a story, even a mystery, behind majestic castles to merchant carts are potent carrots to drive a player's investment. Questions are born, and as curious creatures we must have answers. Complete revelations aren't necessary, however. Ambiguity, with enough hints for the player to ponder over, serves to create worlds alive with possibilities or emotions.

Interestingly, when mythology is not created wholesale but borrowed from real-world influences, the thrill of exploration grows. The completely unknown is fascinating, but also somewhat difficult to relate to. We don't have as strong a reference point for it. Meanwhile, Uncharted and Tomb Raider (specifically its latest reboots) rely on familiar mysteries. Depending on the content, this can the rather fun effect of making us ask, if just for a moment, "What if?" What if there really is a Byzantium-era ship lodged in mountainous ice somewhere? What actual treasures are still left undiscovered? Could there be a hidden source of everlasting life guarded by ancient sects? The answers may be improbable, but we're driven to seek them in the games that much harder. After all, those questions inspire imaginations, and little is more rewarding than indulging the "What if?" of the wonderful. Doing so denies us our daily pessimism.

Tales of Zestiria doesn't quite rely on asking us, "What if?" But character excitement and medieval inspirations give it a fairy tale-like atmosphere. An early quest has the protagonists confronting the sword in the stone myth, complete with its own lady of the lake. Enemies and gods are recognizable from older eras. These are stories and figures we grew up with, but they don't have to leave us as adults. Tales of good versus evil continue to resonate regardless of age. Zestiria resonated for that very reason, aided by a cast of charming friends and a spirit of adventure missing from so many other games. It's not a bad way to play the hero.

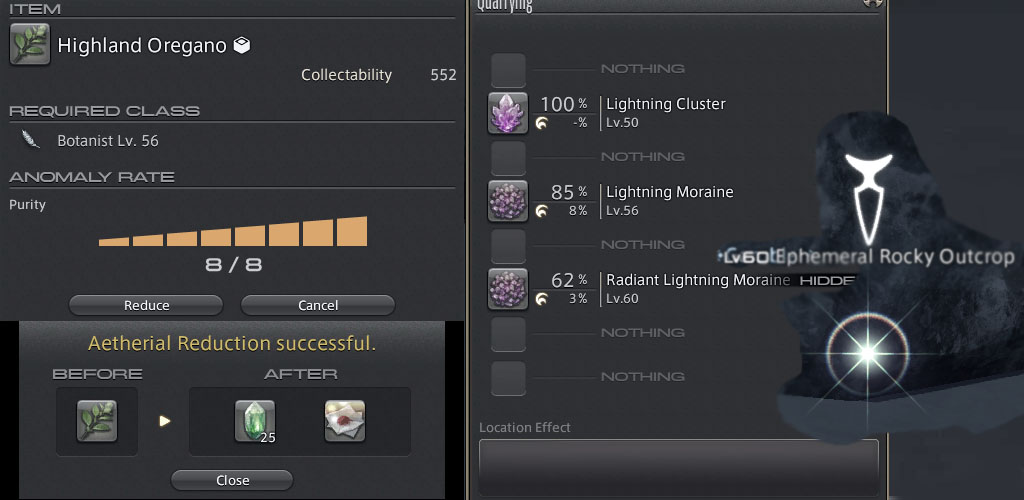

FFXIV: The Deal With Ephemeral Nodes and Aetherial Reduction

FFXIV: The Deal With Ephemeral Nodes and Aetherial Reduction Professor Layton and the Miracle Mask Guide

Professor Layton and the Miracle Mask Guide Inazuma Eleven 3: Secret Locations of Boxes

Inazuma Eleven 3: Secret Locations of Boxes Cities: Skylines (PC Game) review

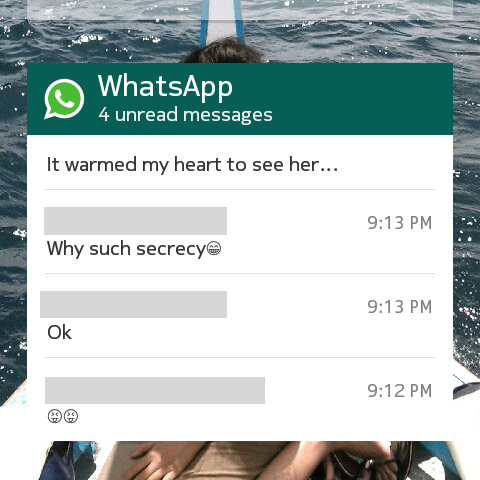

Cities: Skylines (PC Game) review How to Read WhatsApp Messages Without Alerting the Sender

How to Read WhatsApp Messages Without Alerting the Sender