That Dragon, Cancer is a true story. Amy and Ryan Green lost their son, Joel Green, to brain cancer in March of 2014. Games as documentation of actual events are largely untested. How do you communicate grief and healing in a medium preoccupied with entertainment? The answer isn’t all that different from any other medium: tell the story.

And that’s what happens, for the most part. That Dragon, Cancer is a tour through a series of point-and-click vignettes that document Joel’s battle with cancer. In a first-person sequence, I pushed him on a merry-go-round. In another, the camera assumed a fixed perspective as I moved the cursor between limp constellations, turning them into animated creatures so a celestial Joel could take turns riding them. Later on, I assumed Ryan’s perspective and tried to quiet a fussy, tortured Joel with some juice, only for him to vomit it up. Throughout, the family’s reaction to news (good and bad) plays out through ambient audio conversations, scripted sequences, spoken poetry, and diary entries.

For the same reasons that we see films or read books about difficult topics, games like That Dragon, Cancer are valuable. Claudia Rankin’s book Citizen flips the table on race. The Act of Killing brings light to the Indonesian killings of 1965 to 1966 and forces the audience to spend time with terribly violent men. It’s possible for difficult media to jostle us out of stagnancy, to see the world, concepts, people in a new way, and games don’t often make an attempt as bold and earnest as That Dragon, Cancer. In one of what are many torturous sequences, an inconsolable, terminally ill Joel wails at the top of his lungs while Ryan loses himself and sends a few desperate prayers to the sky. Afterwards, I called my parents. We talked about the weather in Montana and how the dogs are doing.

In exploring such untested territory for games, Numinous Games loses its message during the more conceptual moments: the awkward ‘mini-game’ sections and surreal set pieces. In one, you control Joel as he hangs from a bouquet of inflated medical gloves and floats toward a distant planet. Black cancerous spores threaten to pop the gloves if I move too close, and they eventually increase in number until reaching the planet is impossible. As a gameplay metaphor, it failed because I spent more time thinking about how awkward the sequence was to control than the content of the scene. The gamey vignettes don’t need to be ‘fun,’ but I wish my input felt invisible, so I could actively participate in every moment. Similar scenes make up the majority of the latter half of the game, and each forced a bout of aimless clicking and mouse waving while I tried to figure out what I could do before the sequence ended.

That Dragon, Cancer worked when it simply invited me into a recognizable space and let me explore in first person. A quiet hospital scene was the most powerful for me. There’s a short spoken intro from Amy, and then I’m free to wander a few halls and rooms where dozens of cards are strewn about. Each contains a short message, most in honor of actual cancer victims. Leaving one of these sad mementos was, almost unbelievably, a reward tier in the game’s Kickstarter campaign. Every card is a neutron star, signifying their own story of love and loss, a reminder that cancer is a terrible, widespread monster and not just cloistered away into convenient little narratives when we need a good cry. In a week, we lost David Bowie and Alan Rickman. In my lifetime, a friend, a grandparent—that’s just me, though. This is That Dragon, Cancer’s greatest success, it’s ability to suck me into a small story and then, in a quiet moment, reveal the universal scale of its primary themes.

During the last third of the game, the family becomes more dependent (and troubled with) their Christian faith, and I started to decouple from the game. Without belief in the afterlife, I process loss differently. The distance between the Greens and me grew even though my empathy kept trying to close the gap.

But watching Ryan and Amy and Joel’s avatars in each scenario, hearing real emotion in their VO, scrutinizing every polygon and color and realizing it was all created just as an attempt to cope? That Dragon, Cancer may be the distillation of a family’s immeasurable grief expressed through a Christian lens, but grief is a universal anchor. What really matters here are the people involved, the chance to skim the surface of something beyond my own experience, internalize that experience, and use it to bolster my empathy for others.

This story doesn’t have a happy ending, exactly.

The religious segments aren’t ripped from a Sunday School coloring book, anyway—they’re mostly dark, desperate affairs. There’s a particular vignette that takes place in a crystalline church. A keyboard appears in front of me, and pressing each key plays a low note or triggers a line of frenzied prayer from one of the parents. I can light candles surrounding the keyboard, but they go out before I light them all. Within a minute, I’m furiously clicking every candle and jamming on every key. The lights flicker and a cacophony of tired voices ring out. It’s a battle against darkness and silence, an invocation for divine intervention that’s never answered. This story doesn’t have a happy ending, exactly.

Despite the jarring input and my spiritual disconnect, That Dragon, Cancer is unlike any game I’ve experienced. I want everyone to play it. Even if it doesn’t tell its story in the best way, it tells a necessary story. Once I finished, I was immediately reminded of a quote from a Charles Yu novel: “At some point in your life, this statement will be true: tomorrow you will lose everything forever.” We all inevitably lose everything. That Dragon, Cancer is a brave family’s journey through true loss and the search for relief. It’s not a guarantee that we’ll all be OK through thick and thin. The story is too personal for that kind of reassurance. More than anything, That Dragon, Cancer struck me as a terrifying, true question: What will I do when I start to lose it all?

How to Beat Laurence, the First Vicar in Bloodborne: The Old Hunters

How to Beat Laurence, the First Vicar in Bloodborne: The Old Hunters Virtual Reality or Virtual Fad?

Virtual Reality or Virtual Fad? Portal 2 Once Had Everything That Made it a Portal Game Cut Out

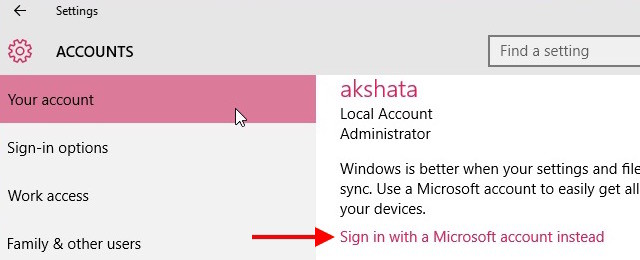

Portal 2 Once Had Everything That Made it a Portal Game Cut Out Create a Microsoft Account on Windows 10 Using Gmail or Yahoo!

Create a Microsoft Account on Windows 10 Using Gmail or Yahoo! Unlocking Fallout 4 Early: Seven Things You Shouldnt Do

Unlocking Fallout 4 Early: Seven Things You Shouldnt Do