Sleep is Death is a two-player turn-based storytelling kit. One player is the director, who creates a scenario using either the included resources or by making their own tiles, objects, characters and even music. When ready, they start a game and invite a second player: the actor. That’s when all hell breaks loose.

With each turn, the actor has 30 seconds to use three abilities: move, act and talk. With those, it’s possible to do almost anything. In our first game we licked a cactus, decided our daughter was really a 17-year-old dwarf, and tried to rob our neighbour. In each instance, the director had their own 30-seconds to type dialogue responses and change the environment accordingly.

So when in the same game we vomited and the director didn’t have a sprite for a puddle of sick in his resources, he was able to draw and place it. This is the amazing, near infinite potential of Sleep is Death: we wanted to vomit, and we could.

To cover all these possibilities, the director’s tools are more complex than the actor’s, including editors that let you change any sprite and music on the fly. It doesn’t take long to get comfortable with them, but even when you’re experienced, the 30-second turn length feels short.

Our second game was a detective story in which we were investigating a dead body found in the woods. While world control lies with the director, an actor dictates a lot. We played Davis, a neurotic who distanced himself from uncomfortable situations by narrating them out loud, and who had a serious crush on his partner.

There’s nothing stopping you from telling a serious and heartfelt tale, except for other players. Give a gamer free will and they will be silly. This isn’t a bad thing – Sleep is Death is often hilarious – but a director has to be skilled at gently leading an actor and making quick judgment calls about which requests to ignore. If a player clicks Act and types ‘Fly,’ does that mean he can fly?

Our second director had decided the killer would be a taxidermist, but he hadn’t guessed we’d pretend to be a customer and would need to deliver a dead dog. He quickly created a new scene in which we went to our house, to our very much alive dog. We called him Professor Snufflekins... and bludgeoned him to death. Our detective story soon became a dark comedy.

It’s such a simple concept: two people defining a story together through play. The only limits are imagination and resources. The latter are easily shared, and with enough players a bank of great art and music will follow. As for imagination, if the screenshot flipbooks appearing online are any indication, with their tales of space plagues, platforming Hitlers and murderous Guybrushes, there’s no shortage of that either.

Apr 22, 2010

Sword Art Online RE: Hollow Fragment Fast and Easy OSS Implementation

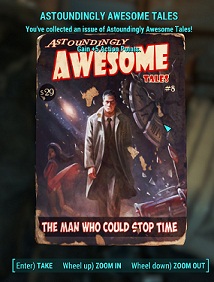

Sword Art Online RE: Hollow Fragment Fast and Easy OSS Implementation Fallout 4 - Locations of all 14 Astoundingly Awesome Tales

Fallout 4 - Locations of all 14 Astoundingly Awesome Tales The Map and the Territory: Why Other Players Enrich Everything You Play

The Map and the Territory: Why Other Players Enrich Everything You Play Gears of War 4 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game .

Gears of War 4 Wiki – Everything you need to know about the game . Shank Walkthrough

Shank Walkthrough