Digital advertising is a phenomenally lucrative industry—in just the first six months of 2015, revenue in the sector totaled $27.5 billion, according to Advertising Age. As in all forms of advertising, digital agencies face a constant battle to keep the attention of consumers. And as we get more adept at mentally and programmatically blocking out advertisements online, new strategies are devised.

One of the tactics that’s become very popular in the past few years is native advertising. It’s a controversial practice, as it uses ads that look like normal editorial content.

Did you know that advertisers are sneaking ads in this way? Do you know how to spot native advertising? And what will the future hold for this form of marketing?

Let’s check it out.

If you’re not familiar with native advertising, it might be hard to visualize without an example. Here’s one from BuzzFeed, a company that has made their fortune through promoted posts (Ralph Legini, the Senior Creative Strategist at DragonSearch Marketing, told me that the BuzzFeed fee for a native ad starts in the six figures).

Looks like a regular BuzzFeed post, right? It certainly does . . . until you get to the very bottom.

Turns out this wasn’t just a regular post — it’s an ad for the TV show Younger. This might not upset you, as the listicle is pretty much the same as any other post from BuzzFeed. But many other sites that are trusted for sharing valuable information also post native advertisements. Here’s an example from Fast Company, who included this ad in their Infographic of the Day column in 2012:

If you look carefully, you can see that the infographic says “Advertisment” above it. The Federal Trade Commission requires that any native advertising be labeled as such to prevent the deception of consumers. Obviously, the degree to which the labeling needs to be obvious is subject to interpretation.

Sometimes you’ll see “Advertisement” or “Ad” on the post, but sometimes you’ll see “Sponsored Post,” “Featured Post,” “Suggested Post,” “Featured Partner,” or other labels that are less obvious. Forbes, for example, just calls it “BrandVoice”:

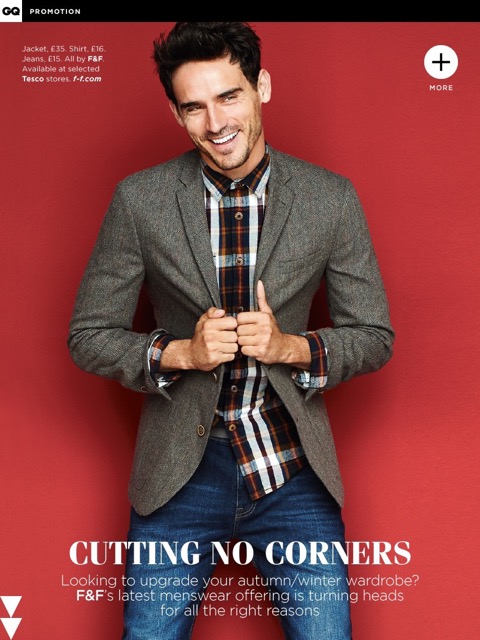

If all of this is sounding familiar, you might be thinking of the advertorial, a word used to describe native advertising that’s used in print, mostly in magazines. Here’s an example of an advertorial from GQ:

It looks exactly like a regular GQ page, but it’s an ad from a retailer. And while it says “GQ Promotion” at the top of the page, you could easily miss that if you just turn the page and start reading — which is what advertisers are hoping you’ll do.

Native ads are increasingly showing up in social media, too, where they look like posts from companies that you liked or followed, such as this one in my Facebook feed from CyberLink:

It looks exactly like the posts I see from Anker, teeVillain, LastPass, and other companies that I follow on Facebook. These ads are easy to identify because of the “Suggested Post” label, but the fact that they show up right in the feed makes them a form of native advertising.

Interestingly, native advertising isn’t always visual; it’s also used on the radio and in podcasts. My wife listens to a lot of podcasts, and she can tell by the background music that a certain section of Reply All or StartUp is an advertisement, but to me it just sounds like a regular segment. Skip to 19:10 or listen to the whole show, as it’s about advertising in podcasts.

For a more detailed overview of native ads in podcasting, be sure to check out the New York Times’ fantastic article on this very issue.

Advertisers face a tough challenge; according to a 2011 Business Insider article, consumers are more likely to summit Mt. Everest, get accepted to Harvard, win the Mega Millions, or survive a plane crash than click on a banner ad. So advertisers need to come up with new strategies to get eyes and click on their ads.

But is native advertising ethical?

Some people think that the type of native advertising matters — for example, we might accept native advertising for products and services as one of the necessary evils of using the Internet. But a few months ago, some people were upset by BuzzFeed’s announcement that it would be hosting native video ads for political campaigns.

When the future of the country is at stake, should we be worried about ads that try to trick users into changing their beliefs?

In a great blog post on Ishmael’s Corner, some of the complexities of native advertising are pointed out in detail. For example, Google indexes native advertising as regular content when it comes from sites that are largely editorial, meaning that you could be shown ads that aren’t identified as such on a Google results page, potentially making it more difficult to identify native ads. (Read the entire article for some other issues with the medium.)

Then again, how else are advertisers going to get us to see their ads?

We don’t click on banner ads. We often don’t see them, as the world is getting increasingly ad-blocker-happy in response to a barrage of intrusive ads and new threats of malvertising. What are advertisers left with, other than native advertising? They could try to change their strategies for banners and sidebars, but when they’re already being blocked, who would notice?

It’s easy to see why native advertising is so appealing to advertisers, and its also obvious why consumers are a bit skeptical of the practice. At least for the moment, we’re at an impasse. We may not like native ads, but we’ve left advertisers with few other options.

While the merits, dangers, and mechanics of native advertising are being hashed out, the best thing you can do is to keep a critical eye open when you’re using the Internet (or consuming any media, really). Watch out for signs that the content you’re reading might be sponsored by an advertiser — as I mentioned, look for tags like “Suggested Post,” “Featured Partner,” and so on. You might be surprised how often you’ll see them.

We even have sponsored posts on MakeUseOf (though they’re much better marked than the ones you’ll find on other sites):

Unfortunately, you’ll have to look more closely on many sites to determine whether or not you’re looking at an ad or editorial content. Keep an eye out when you’re browsing social media, too, and be aware that native advertising can show up anywhere, even in print or audio.

When I emailed Ralph Legini for an article on political ads on Facebook, I asked about the increasing prevalence of native political ads and their potential for deception, and he responded with a question that sums up the issue nicely: “So what else is new? . . . That’s the nature of advertising — real to a point blended with something that perhaps crosses the thin line into the zip code of disingenuous.”

What do you think about native advertising?

Obviously, I’m a bit conflicted—without ads, the Internet wouldn’t be nearly as big or useful as it is. On the other hand, native ads can be very deceiving.

Do you think native ads are sufficiently marked? Should they be allowed at all? How else might advertisers reach us? Share your thoughts below and let’s hash this complicated issue out together.

Image Credits: Designs Fever,

Splinter Cell: Conviction High-Def Wallpapers

Splinter Cell: Conviction High-Def Wallpapers Read More Intelligent Content in 2016 with These 35 Sites

Read More Intelligent Content in 2016 with These 35 Sites Mad Max strategy guide and tips

Mad Max strategy guide and tips 10 Classic FPS games that have been the pride and joy of PC gamers

10 Classic FPS games that have been the pride and joy of PC gamers Sony Unveils PS4 Features at GDC, Including PS4 Eye

Sony Unveils PS4 Features at GDC, Including PS4 Eye